Acne, who isn’t familiar with it? Almost everyone ‘catches’ it to some degree or another around puberty. Even many people still suffer from it in adulthood, with the condition estimated to persist into the 20s and 30s in around 64% and 43% of individuals, respectively [1]. While the condition is easy to recognize clinically, its pathogenesis (the process by which it develops) is extensively complex and researchers worldwide are still deciphering it bit by bit.

Feel free to skip over to the final section of this article if you’re just looking for an example treatment regime.

In general, acne is thought to result from the following four pathogenic factors (in no particular order) [2, 3]:

- Increased sebum production

- Abnormal keratinization

- Release of inflammatory mediators into the skin

- Bacterial hypercolonization of the hair follicle by Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes, formerly known as Propionibacterium acnes [P. acnes])

An increased sebum production per se isn’t much of a problem in the sense that it would just give a greasy skin. However, it’s thought to contribute to acne by providing a more comfortable environment for C. acnes and alteration of the composition of fatty acids in sebum. In particular, a decrease in its linoleic acid content. Taken together, this in turn might disturb the barrier function of the follicular walls of the keratinocytes (cells that make up the hair follicle) [4] and lead to an inflammatory cascade [5].

The abnormal keratinization refers to these cells not shedding normally like they should. Instead of sloughing off and being pushed onto the skin surface, they become cohesive and stick around in the hair follicle—essentially clogging it. It is thought this is an early event in the development of a comedone, yielding a microcomedone.

Androgens play a role in both of these. For example, androgen-insensitive men fail to produce demonstrable levels of sebum and don’t appear to develop acne [6]. This signifies that, at least some, androgenic activity is required for developing acne. A trial in which men first received ethinylestradiol (which would markedly suppress endogenous testosterone production), and subsequently received concurrent administration of testosterone, showed that the addition of testosterone led to a notable increase in sebum production [7]. Finally, the well-known testosterone researcher Shalender Bhasin and his group measured sebum production in men receiving graded dosages of testosterone (50, 125, 300, or 600 mg weekly) with or without the 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride for 20 weeks [8]. They found that sebum production in the forehead region, but not on the nose or back, was related to testosterone dose. However, the association was week and the 600 mg group even saw a, albeit non statistically significant, decrease in their sebum score. Sebum production might seemingly play a less important role in AAS-induced acne than expected. Indeed, oily skin was hardly reported by the subjects, whereas acne was more frequently reported.

Further interesting data with regard to the incidence of acne as a result of anabolic steroid use in high dosages comes from the HAARLEM trial [9]. Briefly, the HAARLEM trial was a prospective cohort study in which 100 anabolic steroid users were followed over time while they self-administered AAS [9]. Mean dosage, based on label information, was 898 mg per week, thus making their AAS cycle quite representative of common usage by bodybuilders. Measurements were taken before, during, as well as 3 months after the end of their cycle and 1 year after the start of their cycle. The researchers visually examined the skin for acne and at baseline 13% of the users were found to have acne. This increased to 29% at the end of the cycle, and dropped back to 23% 3 months after the cycle, and 10% 1 year after the start of the cycle. Self-reported acne was notably higher at the end of their cycle, with 10% at baseline, 52% at the end, 29% 3 months after, and 14% 1 year after the start of the cycle.

Clearly, acne is a common side effect of AAS usage in high dosages. But what can be done about it? In this article I’ll outline some treatment modalities. A word of caution is in place, however, as none of these trials evaluated the effects of these treatment modalities in AAS-induced acne specifically. However, it’s very reasonable to assume that they can work in this situation too.

Over the counter oral supplements: zinc, vitamin D, omega 3 fatty acids

While its mechanism of action remains somewhat elusive, oral zinc supplementation has been found to be effective against in several clinical trials [10]. Its efficacy in the treatment of acne was first noticed by Fitzherbert [11] and Michaëlsson et al. in the 1970s [12]. Giving zinc-deficient patients zinc improved their acne, and Michaëlsson et al. even initiated a double-blind trial. In it, it compared zinc supplementation to an oral antibiotic (oxytetracycline) in the treatment of acne. The zinc group received 45 mg of elemental zinc daily in the form of zinc sulfate. They found no difference in results between the groups, with an average decrease in acne score of 70 % in both of them. A literature review describes the results of 8 placebo-controlled trials, of which half of them found a significant objective improvement in acne in those treated with zinc compared to those receiving placebo [10]. One of the reasons why not all trials found an improvement might lie in a lack of statistical power, as well as zinc status and severity of acne of the test subjects (it’s been suggested that zinc is more effective in severe acne than mild-to-moderate acne [13]). Dosages used in the studies vary quite a bit, and there doesn’t seem to be a clear relation between dosage and results. As such I would recommend not to exceed the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) of 40 mg elemental zinc daily.

Vitamin D might be another over the counter supplement that might help in the battle against acne. A randomized-controlled trial of vitamin D deficient (<30 nmol/L 25[OH]D) subjects showed that a daily supplement of 1,000 IU vitamin D for 8 weeks led to a significant decrease in inflammatory lesions compared to placebo [14]. Given that a lot of people are vitamin D deficient, correcting this with a supplement might be a good idea. For example, a Dutch study found that about two-thirds of a sample of 128 highly trained athletes were either vitamin D deficient (<50 nmol/L 25[OH]D) or insufficient (<75 nmol/L 25[OH]D) [15]. However, 1,000 daily, as used in the trial, is likely to be too low of a dosage to correct a deficiency. Indeed, over the course of those 8 weeks it increased levels from 20 nmol/L to 40 nmol/L in the study, which is still deficient as per the guidelines of the Endocrine Society [16]. Serum 25(OH)D levels above 75 nmol/L are considered adequate. Most would likely require a dosage of 2,000 IU daily or higher. A daily intake of 4,000 IU has been set as the tolerable upper limit of intake by the European Food and Safety Authority [17].

Finally, a randomized placebo-controlled trial found supplementation of omega 3 fatty acids (1 g eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and 1 g of docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) daily to decrease acne severity in subjects with mild to moderate acne [18].

Topicals: benzoyl peroxide and retinoids

Benzoyl peroxide is available over the counter as a cream in most countries (I don’t think there’s any country which requires a prescription for it). It’s reasonably effective (although most trials suck quality-wise) [19] and particularly so against C. acnes. Additionally, it seems to help a bit in regard to the follicular keratinization [20]. However, while it does make your skin dry (damn dry), it doesn’t actually seem to lower sebum production. It likely makes the skin dry by virtue of its oxidative capacity: oxidizing the lipids which would otherwise make your skin feel smooth.When using this, it’s recommended to apply a thin layer of benzoyl peroxide on the affected areas once daily. The preparations with a 2.5-5 % concentration, instead of a more concentrated one, should be preferred [21]. Side effects include dry skin, redness of the skin, irritation of the skin, pruritus (itching), and possibly, on rare occasions, contact dermatitis. Also be sure to apply sunscreen on sunny days, as it makes the affected areas more prone to sunburn. Finally, it has a strong bleaching effect, so don’t go out and about and wipe your face (or your hands that just got in contact with it) over textiles. It’s notorious for ruining pillowcases, towels and shirts.

Topical retinoids are available over the counter in some countries, but others require a prescription (including mine, the Netherlands). They’re mainly effective against keratinization, and, to a lesser extent, the inflammatory cascade. As such I believe retinoids to be more effective in the case of AAS-induced acne compared to benzoyl peroxide. Tretinoin is a commonly prescribed retinoid, with others being adapalene (Differin) and tazarotene (Tazorac). They all work comparatively well with slight differences between them. Adapalene seems to be as effective as tretinoin, but showing results slightly faster and being tolerated a bit better [22]. The higher concentrated formulation of Adapelen (0.3% vs 0.1%) seems to work better while being equally well tolerated [23]. In turn, tazarotene demonstrated to be a bit better than adapalene in one trial [24], but demonstrating equal efficacy in another [25], while both demonstrating adapalene being tolerated better. I guess adapalene has some preference because of the slightly better tolerability. Side effects are similar to that of benzoyl peroxide. Manufacturer’s recommendation is to start with once daily dosing or every other day. However, this stuff is quite harsh on your skin, twice a week might be a better starting point and work your way up from there.

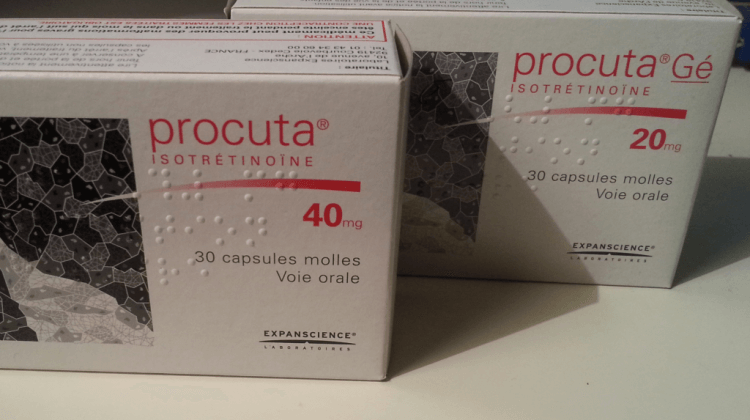

Isotretinoin (Roaccutane/Accutane)

Frankly the god of all acne treatments. It works very well [26] and targets all four factors involved in the pathogenesis of acne. It’s only available on prescription (and rightfully so). Usually, dosages around 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg bodyweight daily are prescribed. However, lower dosages, even as low as 5 mg daily [27], are also quite effective and they’re a lot better tolerated. Which is very welcome, since the treatment comes with quite some annoying side effects, mostly dermatological. This includes dry chapped lips, dry skin, pruritus, dry eyes and nose bleeds. When prescribed, blood tests are performed (commonly at baseline, after 1 month of treatment and then every 3 months). The reason for this is that isotretinoin might increase cholesterol, triglycerides, and markers of liver damage, and might decrease hemoglobin. However, a systematic review reported abnormal blood work in 4% of those treated with isotretinoin (and only 0.1% in the control groups) [26], with only 1 in 200 patients needing to stop treatment as a result of abnormal blood work (elevated liver enzymes). Notably, psychiatric/psychosomatic events were found to be about 50% more frequent in those using isotretinoin compared to control groups. In particular, “suicidal thoughts” and “suicide” are listed in the isotretinoin leaflet as side effects. This is more out of caution than that a causal link has actually been established (because of the rarity it’s very hard to do this). Finally, some odd trial described that EPA and DHA supplementation (seemingly 1 g in total, but the trial failed at describing this clearly) is helpful against some of the dermatological side effects [28]. For AAS-induced acne, if other treatment modalities aren’t leading to satisfactory results, I feel a low dosage in the ballpark of 5 to 10 mg daily is most appropriate. Higher dosages, as commonly prescribed in ‘regular’ acne vulgaris, seem unwarranted.

Example treatment regime

A good place to start would be by using the over the counter supplements available: zinc (up to 40 mg daily), vitamin D (1,000-4,000 IU daily), and omega 3 fatty acids (1 g EPA and 1 g DHA daily). If this is insufficient, one might add a retinoid (such as adapalene 0.3%) or benzoyl peroxide (2.5-5%) and apply it to the affected areas. Once daily for benzoyl peroxide, and twice a week as a starting point for the retinoid. The two can also be combined, by applying, for example, benzoyl peroxide in the morning and the retinoid in the evening. If after several weeks results are still unsatisfactory, one might opt for isotretinoin at a low dosage of 5 to 10 mg daily. (Do note that acne might get worse initially during the first few weeks.)

Bonus: 5α-reductase inhibitors don’t appear to work

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, 5α-reductase inhibitors, which inhibit the conversion of testosterone to the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT), don’t appear to help against acne. Why? This is unclear.

A well-designed 3-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 182 subjects compared the effect of a selective type 1 5α-reductase inhibitor to an antibiotic (minocycline, a standard treatment for acne at the time, although now it’s use is discouraged standalone) [30]. Type 1 5α-reductase is richly expressed in the sebaceous gland [31], and indeed a selective type 1 inhibitor shows a greater decrease in sebum DHT than finasteride (which isn’t potent at inhibiting type 1, only type 2 and 3) [32]. Additionally, they also evaluated whether the combination of minocycline with the type I inhibitor worked better. The type I inhibitor worked as well as the placebo. Combination therapy also didn’t improve efficacy, as it worked as well as minocycline alone.

There’s also a large (106 participants enrolled) placebo-controlled trial that’s registered by the pharmaceutical company Elorac (NCT02502669) in which subjects received finasteride (23.5 mg daily or 33.5 mg daily) in the treatment of acne. While the study was completed in 2017, the results have never been published. I suspect because finasteride simply didn’t do any better than placebo. (And god those dosages are high.)

References

- Bhate, K., and H. C. Williams. “Epidemiology of acne vulgaris.” British Journal of Dermatology 168.3 (2013): 474-485.

- D. Thiboutot, H. Gollnick, V. Bettoli, B. Dréno, S. Kang, J. J. Leyden, A. R. Shalita, V. T. Lozada, D. Berson, A. Finlay, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne group. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 60(5):S1–S50, 2009

- Williams, Hywel C., Robert P. Dellavalle, and Sarah Garner. “Acne vulgaris.” The Lancet 379.9813 (2012): 361-372.

- P. M. Elias, B. E. Brown, and V. A. Ziboh. The permeability barrier in essential fatty acid deficiency: evidence for a direct role for linoleic acid in barrier function. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 74(4):230–233, 1980.

- A. H. Jeremy, D. B. Holland, S. G. Roberts, K. F. Thomson, and W. J. Cunliffe. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 121(1):20–27, 2003.

- Imperato-McGinley, Julianne, et al. “The androgen control of sebum production. Studies of subjects with dihydrotestosterone deficiency and complete androgen insensitivity.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 76.2 (1993): 524-528.

- Pochi, Peter E., and John S. Strauss. “Sebaceous gland response in man to the administration of testosterone, D4-androstenedione, and dehydroisoandrosterone.” J Invest Dermatol 52 (1969): 32-36.

- Bhasin, Shalender, et al. “Effect of testosterone supplementation with and without a dual 5α-reductase inhibitor on fat-free mass in men with suppressed testosterone production: a randomized controlled trial.” Jama 307.9 (2012): 931-939.

- Smit, Diederik L., et al. “Positive and negative side effects of androgen abuse. The HAARLEM study: A one‐year prospective cohort study in 100 men.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 31.2 (2021): 427-438.

- Cervantes, Jessica, et al. “The role of zinc in the treatment of acne: A review of the literature.” Dermatologic therapy 31.1 (2018): e12576.

- J. Fitzherbert. Zinc deficiency in acne vulgaris. The Medical journal of Australia, 2(20):685–686, 1977.

- G. Michaëlsson, L. Juhlin, and K. Ljunghall. A double-blind study of the effect of zinc and oxytetracycline in acne vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology, 97(5):561–566, 1977.

- Y. S. Bae, N. D. Hill, Y. Bibi, J. Dreiher, and A. D. Cohen. Innovative uses for zinc in dermatology. Dermatologic clinics, 28(3):587–597, 2010.

- S.-K. Lim, J.-M. Ha, Y.-H. Lee, Y. Lee, Y.-J. Seo, C.-D. Kim, J.-H. Lee, and M. Im. Comparison of vitamin d levels in patients with and without acne: a case-control study combined with a randomized controlled trial. PloS one, 11(8):e0161162, 2016

- Backx, E. M. P., et al. “The impact of 1-year vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D status in athletes: a dose–response study.” European journal of clinical nutrition 70.9 (2016): 1009-1014.

- M. F. Holick, N. C. Binkley, H. A. Bischoff-Ferrari, C. M. Gordon, D. A. Hanley, R. P. Heaney, M. H.Murad, and C. M. Weaver. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin d deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 96(7):1911–1930, 2011

- N. EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products and A. (NDA). Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level of vitamin d. EFSA Journal, 10(7):2813, 2012.

- J. Y. Jung, H. H. Kwon, J. S. Hong, J. Y. Yoon, M. S. Park, M. Y. Jang, and D. H. Suh. Effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acid and gamma-linolenic acid on acne vulgaris: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Acta dermato-venereologica, 94(5):521–526, 2014.

- N. H. Mohd Nor and Z. Aziz. A systematic review of benzoyl peroxide for acne vulgaris. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 24(5):377–386, 2013.

- J. Waller, F. Dreher, S. Behnam, C. Ford, C. Lee, T. Tiet, G. Weinstein, and H. Maibach. ‘keratolytic’ properties of benzoyl peroxide and retinoic acid resemble salicylic acid in man. Skin pharmacology and physiology, 19(5):283–289, 2006.

- A. J. Brandstetter and H. I. Maibach. Topical dose justification: benzoyl peroxide concentrations. Journal of Dermatological Treatment, 24(4):275–277, 2013

- W. Cunliffe, M. Poncet, C. Loesche, and M. Verschoore. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.1% gel versus tretinoin 0.025% gel in patients with acne vulgaris: a meta-analysis of five randomized trials., 1998

- D. Thiboutot, D. M. Pariser, N. Egan, J. Flores, J. H. Herndon Jr, N. B. Kanof, S. E. Kempers, S. Maddin, Y. P. Poulin, D. C. Wilson, et al. Adapalene gel 0.3% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase iii trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 54(2):242–250, 2006.

- E. Tanghetti, S. Dhawan, L. Green, J. R. Del, Z. Draelos, J. Leyden, A. Shalita, D. A. Glaser, P. Grimes, G. Webster, et al. Randomized comparison of the safety and efficacy of tazarotene 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.3% gel in the treatment of patients with at least moderate facial acne vulgaris. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 9(5):549–558, 2010.

- D. Thiboutot, S. Arsonnaud, and P. Soto. Efficacy and tolerability of adapalene 0.3% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Journal of drugs in dermatology: JDD, 7(6 Suppl):s3–10, 2008

- I. Vallerand, R. Lewinson, M. Farris, C. Sibley, M. Ramien, A. Bulloch, and S. Patten. Efficacy and adverse events of oral isotretinoin for acne: a systematic review. British Journal of Dermatology, 178(1):76–85, 2018.

- M. Rademaker, J. Wishart, and N. Birchall. Isotretinoin 5 mg daily for low-grade adult acne vulgaris–a placebo-controlled, randomized double-blind study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 28(6):747–754, 2014.

- M. Mirnezami and H. Rahimi. Is oral omega-3 effective in reducing mucocutaneous side effects of isotretinoin in patients with acne vulgaris? Dermatology research and practice, 2018.

- J. Leyden, W. Bergfeld, L. Drake, F. Dunlap, M. P. Goldman, A. B. Gottlieb, M. P. Heffernan, J. G. Hickman, M. Hordinsky, M. Jarrett, et al. A systemic type i 5 a-reductase inhibitor is ineffective in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 50(3):443–447, 2004.

- F. Azzouni, A. Godoy, Y. Li, and J. Mohler. The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: a review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. Advances in urology, 2012, 2012.

- F. Azzouni, A. Godoy, Y. Li, and J. Mohler. The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: a review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. Advances in urology, 2012, 2012.

- J. I. Schwartz, W. K. Tanaka, D. Z. Wang, D. L. Ebel, L. A. Geissler, A. Dallob, B. Hafkin, and B. J. Gertz. Mk-386, an inhibitor of 5a-reductase type 1, reduces dihydrotestosterone concentrations in serum and sebum without affecting dihydrotestosterone concentrations in semen. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 82(5):1373–1377, 1997.

About the author

Peter Bond is a scientific author with publications on anabolic steroids, the regulation of an important molecular pathway of muscle growth (mTORC1), and the dietary supplement phosphatidic acid. He is the author of several books in Dutch and English, including Book on Steroids and Bond's Dietary Supplements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.