The use of anorectic drugs in medicine has always been a highly controversial issue. It is generally accepted that the problem of obesity comes more from behavior rather than genetics. Many doctors believe that diet drugs should not be used, and instead people wishing to lose weight should simply eat less and exercise. Sounds easy enough, doesn’t it? Why bother with all the health risks of diet drugs?

Obviously, things aren’t so simple as “eat less and exercise” or we would have found a cure for obesity centuries ago. There are two main problems with the “eat less and exercise”. The first is that you will only lose weight for three to six months before reaching a plateau. Weight loss is pretty quick for the first three months for almost all diet and exercise plans. Even the best diet and exercise plans start to lose their effectiveness after three months and by six months weight loss almost always stops completely. The second problem is making sure you are losing fat and not muscle. Many poor diet and exercise plans induce almost as much muscle loss as fat loss, while a good plan can reduce muscle loss to almost zero. Diets that contain about 90-100 grams of protein per day for 70-80 kg person are reported to minimize lean mass loss to about 20-30% of total weight loss. Preserving muscle is key for long-term weight loss. Loss of muscle lowers metabolism – making it very difficult to keep the weight off.

So the question of the appropriateness of diet drugs hinges on these issues. If a drug can prolong weight loss for more than the usual six months barrier, it will be a very valuable tool in the fight against obesity. If a drug can help preserve muscle mass (lean mass/non fat mass) while dieting, it can make a huge difference in people’s weight loss plans. Unfortunately, little research has been done to evaluate the effectiveness of diet drugs in these key areas. This article reviews a few of the studies that may lead us to an effective protocol for diet drug use.

Beating the Six Month Plateau

Almost all diet drugs fail to produce weight loss after six months of use. All that diet drugs have been shown to do so far is increase the amount of fat and some lean mass loss (muscle mostly) during the three to six month window of weight loss your body allows, but they have not been shown to extend this window. Your body is a highly adaptive machine, and it adapts quickly to both the effects of your diet and to the effects of diet drugs, which is what makes long-term weight loss extremely difficult.

However, one study shows some promise for a new protocol for diet drug administration. In this study, the widely prescribed anorectic drug phentermine (the phen in “phen-fen”) was administered every day to one group while given intermittently ever other month to another group (1). After nine months, both groups lost more weight than the placebo. However, the intermittent group actually lost slightly more weight than the everyday group. While the difference was small in this study (the intermittent group lost 1.7 more pounds than the everyday group), I believe other drugs would be much more effective than phentermine for intermittent use. It must also be noted that almost all the weight loss occurred in the first six months of the study. Unlike other diet drugs, phentermine does not preserve or increase the levels of the highly active thyroid hormone, T3. When your calories are restricted, T3 levels drop which in turn slows down your resting metabolic rate. This is one the major ways your body adapts to dieting. In one study, phentermine was tested head to head with the FDA-approved anorectic drug mazindol in a 12 day trial (2). At the end of the trial, the mazindol group experienced the largest weight loss. The reason was likely due the fact that subjects taking phentermine or a placebo experienced a drop in T3 levels of over 20%, while the mazindol group’s T3 levels dropped by only 3%.

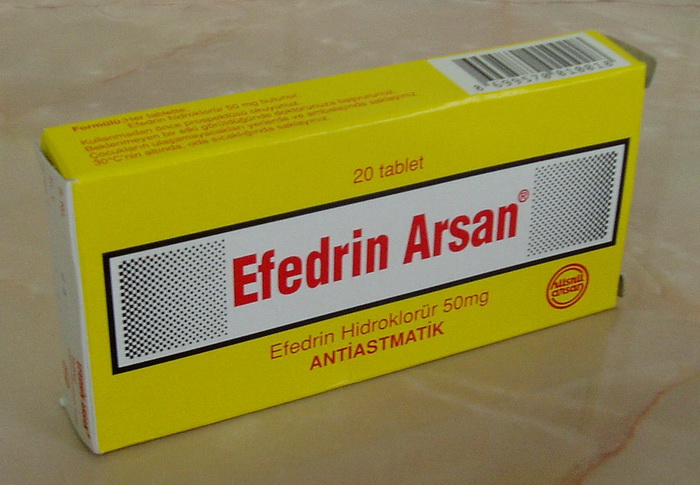

Ephedrine may be even more effective than mazindol at preserving T3 levels. In two separate trials, ephedrine was shown to help maintain or even increase T3 levels in spite of reduce caloric intake (3,4). In one of these trials, T3 levels became elevated after one month of daily use, but T3 levels dropped below baseline after three months (4). This would suggest that the best intermittent pattern for ephedrine use may not be the one-month on, one-month off protocol used in the phentermine study. Since T3 levels are elevated after one month of ephedrine use, it probably makes sense to use ephedrine for longer than one month – perhaps six to eight weeks. Longer use than two months resulted in lower T3 levels, so at this point ephedrine use should be stopped for about a month. While more clinical trials should be done, using ephedrine in a one to two-month on, one month off pattern may be the optimal diet drug protocol. For long-term weight loss, ephedrine’s T3 elevating effects make it the most promising choice of all diet drugs commercially available. Research data on phentermine has also shown that intermittent use of this category of diet drugs may be superior to continuous use. Using ephedrine in an intermittent pattern may well become the best way to prolong the frustrating six month plateau effect seen in most diet plans.

Preserving Lean Mass

For muscle-sparing effects, it is difficult to compare diet drugs since most studies only report weight loss and do not distinguish between fat and muscle loss. However, research suggests that ephedrine may be highly effective for sparing muscle during dieting. One study of obese women showed dramatic effects on preserving muscle (5). In this study subjects were put only a low calorie (1000 per day) diet and given either 20 mg of ephedrine with 200 mg of caffeine or a placebo. At the end of eight weeks weight loss was only 3.7 pounds higher in the ephedrine group. However, fat loss was almost 10 pounds higher! This was because the ephedrine group lost 90% of their weight from fat, while the placebo group only 53% of their weight from fat. This is obviously a huge difference that demonstrates the potential value of diet drugs in preserving lean mass for a long-term weight loss plan. Keep in mind that this study was on obese women, and used only a small sample size (14 subjects). Another study looking at both obese women and men showed ephedrine to have a strong effect in improving nitrogen retention (3). More research needs to done on ephedrine’s muscle sparing effects, specifically in non-obese individuals and in men. Still, the research so far is very impressive and it makes ephedrine or ephedrine/caffeine appear to be highly promising tool for long-term weight loss and muscle preservation. It should also be noted that these studies were short tem, so it is not yet known if ephedrine has muscle sparing effects for use longer than two months. This is another reason to use ephedrine in a one to two month on, one month off pattern.

Keep in mind that these studies are on ephedrine and not the herb ma huang. Ma huang products usually say on the bottle “standardized for 8% ephedra alkaloids,” which really does not tell you much. These ephedra alkaloids do not just include ephedra, but also pseudoephedrine, norephedrine, norpseudoephedrine, and other ephedrine like compounds – all with different properties and effects on your body. Each batch of ma huang will have a different array of these alkaloids and thus an unpredictable effect. As a medical doctor, I prefer the obese person to use pure ephedrine since its effects are well known and well studied rather than take the “shot gun” uncontrolled approach of using ma huang.

A few supplement companies have recently begun to promote diet formulas containing norephedrine (phenylpropanolamine) instead of ephedrine. Norephedrine is less stimulating than ephedrine, which is a big advantage since many complain of over stimulation from ephedrine. Unfortunately, little research has been done to compare the muscle-sparing and T3-stimulating effects of norephedrine. If norephedrine is equally effective as ephedrine in these regards, it may be a better choice than ephedrine. If not, people will have to make a trade-off between less stimulation or greater effectiveness.

Protein: The Ultimate Anorectic “Drug”?

The research on ephedrine has shown that it may well be the superior diet drug. However, I also believe that dietary and lifestyle changes should be made first before diet drugs are administered. Recent research has suggested that simply increasing the proportion of calories from protein in your diet may be highly effective in jump starting your weight loss program. In fact, protein may have “drug-like” effects on appetite that make it a comparable anorectic agent as ephedrine or phentermine. High-protein diets are all the “rage” right now. Many people have reported tremendous results when cutting the carbohydrates and upping their protein intake. High protein/low carb diets such as the Zone Diet and the Atkins Diet are catching on like crazy. Yet to the mainstream weight loss industry, high protein diets are still considered dangerous and radical. Any deviation form the low-fat, high carbohydrate “food pyramid” diet is often taken as heresy by nutrition professors and dieticians. However, a new study will hopefully open people’s minds about the role of protein in an effective fat loss protocol.

A groundbreaking study was published recently in the International Journal of Obesity (6) that suggest the protein may be one the most effective anorectic agents available – comparable to most diet drugs. In a very tightly controlled study, a team of Danish researchers led by A.R. Skov studied the effects of a high protein diet compared to a high carbohydrate diet. 25 people were told to eat a diet consisting of 25% of calories from protein, 45% from carbohydrates, and 30% from fat. Another 25 people were told to eat a diet of 12% of calories from protein, 58% from carbohydrates, and 30% from fat. Test subjects could eat as much as they wanted, provided they eat their macronutrients in these proportions. This study lasted six months, and the test subjects were obese men and women aged 18-55. This study was very well controlled. Test subjects’ diets were monitored very closely, as they got all their food for from a university-run shop. Food selections made by test subjects were recorded by a dietician. Uneaten food was also kept track of by the researchers. To monitor diet compliance even further, urinary nitrogen excretion was measured each month to estimate how much protein test subjects were consuming. Using all this data, the researchers estimated that the actual macronutrient profiles consumed by the test subjects in both groups came extremely close to the targeted 25/45/30 and 12/58/30 ratios. I was also impressed that the researchers used the highly accurate dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning device for body composition measurements.

At the end of the study, the high protein diet proved to be much more effective. Fat loss at the end of six months was 16.7 pounds for the high protein group, while only 10 pounds for the high carbohydrate group. The researchers attributed this increased fat loss from reduced calorie intake by the protein group and from the increased thermogenesis induced by protein. Previous studies have shown that protein satisfies the appetite better than fat and carbohydrates, as well as having a greater thermogenic effect.

Not only does this study vindicate the effectiveness of high protein reduced carbohydrate diets, but it sheds light on some other issues as well. For one thing, high protein diets may be better for long-term fat loss. The high carbohydrate group lost 8.36 pounds the first three months, but less than two pounds over the next three months of the diet. The high protein group, however, lost 12.76 pounds the first three months and continued to lose an impressive four pounds over the last three months of the diet. It appears that the high protein group was slower to reach a plateau than the high carbohydrate group. However, both groups did reach a plateau by the sixth month of the study – which is what we find in almost all weight loss studies.

High protein diets may also be effective for preserving lean mass as well. Both the high carbohydrate and high protein group lost a similar percentage of their weight from fat – about 87% in each group. Unfortunately, it is difficult to measure how much of the remaining 13% of weight loss came from water and how much came from muscle. The researchers are still analyzing the DEXA data and more results from this study may be available in the next few months. However, it may well be the case that the high protein group lost less muscle. For one thing, protein is a known diuretic so it is likely that more of the weight loss came from water. The high protein diet was consuming less carbohydrates so it must have had lower glycogen stores as well – meaning more loss of water. Carbohydrates, on the other hand, are known to increase glycogen and water storage – so less of the weight loss in the carbohydrate group was likely to have come from water. I eagerly await further results from these Danish researchers, but I think it is quite likely that the higher protein intake allowed for higher nitrogen retention and less loss of muscle mass.

Conclusion

Eating less and exercising can only take you so far in reaching your weight loss goals. More research needs to be done, but it appears that moderate, intermittent use of ephedrine may be one valuable part of a long-term weight loss program. I am also excited by the Danish researchers work on high protein diets. I believe one excellent weight loss protocol is to start by simply reducing the simple carbohydrates (starches) in your diet and upping the protein. Protein appears to have powerful effects on suppressing appetite and increasing metabolism comparable to the most effective diet drugs. Combining a high protein diet with regular exercise should be enough for most people to lose weight for six months without using any diet drugs.

However, this six month barrier has been shown in many studies to be close to unbeatable for many people. I believe the best way to break through this plateau is to intentionally avoid the use of any anorectic drugs and simply rely on dietary changes and exercise for the first six months of any weight loss program. At this point, diet drugs may be the only effective option. However, not all diet drugs are created equal. It appears that ephedrine may have superior T3-stimulating and muscle-sparing effects to phentermine and other diet drugs, although much more research needs to be done. It is a good bet that ephedrine is superior to the latest diet drugs Meridia and Xenical. Intermittent use of diet drugs may also be a way to prolonging the drugs’ effectiveness.

Keep in mind that the body is a highly, highly adaptive machine. This is why long term, permanent weight loss requires much more thought than the simple “eat less and exercise” approach. I believe diet drugs do play an important role in weight loss, but only after you have your body has adapted itself to a solid diet and exercise program. The necessity of diet drugs in treating obesity comes from the sad fact that no matter how impressive your diet and exercise program is, your body will inevitably adapt to it.

References

1. Munro, JF, et al. “Comparison of Continuous and Intermittent Anorectic Therapy in Obesity”, British Medical Journal 1:352-354,1968

2. Sonka, J, et al. “Effects of Diet, Exercise and Anorexigenic Drugs on Serum Thryoid Hormones”, Enkokrinologie 1980 Dec;76(3):351-6

3. Pasquali, Renato, et al. “Effects of Chronic Administration of Ephedrine During Very-Low-Calorie Diets on Energy Expenditure, Protein Metabolism and Hormone Levels in Obese Subjects” Clinical Science (1992) 82, 85-92

4. Astrup, Arne, et al. “Enhanced Thermogenic Responsiveness During Chronic Ephedrine Treatment in Man”, The American Journal of Clinical Ntrition 42: July 1985, 83-94

5. Astrup, Arne, et al. “The Effect of Ephedrine/Caffeine Mixture on nergy Expenditure and Body Composition in Obese Woman”, Metabolism 1(7):686-8 1992

6. Skov, AR, et al. “Randomized Trial on Protein vs Carbohydrates in Ad Libitum Fat Reduced Diet for the Treatment of Obesity”, International Journal of Obesity (1999) 23, 528-536

About the author

Warning: Undefined array key "display_name" in /home/thinksteroids/public_html/wp-content/plugins/molongui-authorship-pro/includes/hooks/author/box/data.php on line 11

Warning: Undefined array key "display_name" in /home/thinksteroids/public_html/wp-content/plugins/molongui-authorship-pro/includes/hooks/author/box/data.php on line 11

Warning: Undefined variable $show_related in /home/thinksteroids/public_html/wp-content/plugins/molongui-authorship/views/author-box/parts/html-tabs.php on line 30

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.