Q: Charles, I do a workout where I do nose crushers, then bench press, then power snatches, and finish with ball crunches. I fatigue quickly and haven’t been making progress. Should I up my calories, or is there a supplement you recommend for sustained energy?

A: Although your diet and/or overtraining could be a factor, let’s examine the workout itself. Selecting exercises targeting certain muscles is great, but we cannot lay out the plot without rhyme or reason. As a rule of thumb, always order your exercises from greatest technical difficulty to least technical difficulty. Challenge the nervous system first, since less complicated exercises can still be performed as this system fatigues. After that, select exercises which involve large muscles masses prior to exercises which require lesser volumes of muscle to perform. Consider the exercise relationships logically – compound exercises usually will not affect so-called “isolation” movements; however, the latter will often have a debilitating effect on the former.

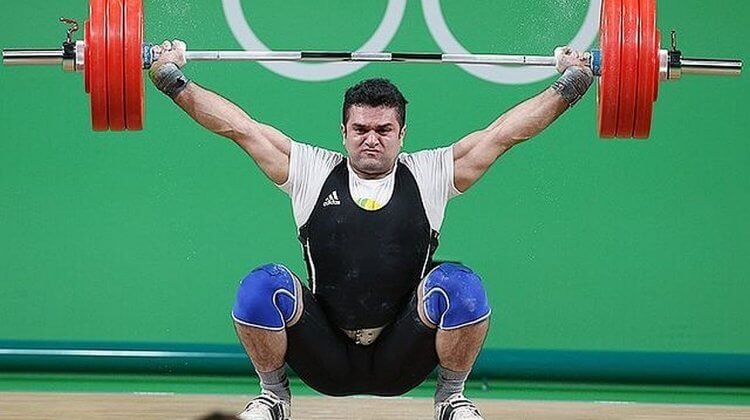

The power snatch requires intense and coordinated use of more muscles than any other exercise in this workout. It does not target a specific muscle like a bicep curl does. Also, the power snatch places great demand on the body’s ability to transfer force from one muscle to another against an external resistance. For these reasons, the snatch is clearly the most technically complicated lift in your workout and certainly should be performed first.

Nothing else in this workout has a particularly high skill element; therefore, we now have to consider which remaining lift will present the greatest intensity. The bench press is a logical choice for the second exercise for two reasons. First, it will require more high threshold muscle fibers than anything left to be performed, and second, nose crushers prior to benching would effect the triceps ability to contribute as a synergist to the pectorals in the bench press.

Performing nose crushers after benching gives the triceps a bout of direct stress that they did not receive during the bench presses. Although the bench press requires significant use of the triceps in the assistance of the pectorals, their role as a synergist should not be so taxing that they will perform at all short of maximum ability.

Finally, I would save the ball crunches for last. Although the addition of the ball would seem to elevate the skill element of the exercise, we don’t want to fatigue and effect the abdominals adversely in their crucial role as stabilizers for all the exercises performed up to this point.

There is a realistic chance that rearranging this routine could solve your problem. I would actually be surprised if there were days you ever felt good snatching after nose crushers and bench presses! These changes are not subtle – you may have the best snatch and bench workouts you have ever had if this exercise order has always been your habit.

Q: Charles: Most people say you can improve your tennis game with strength training; however, I see few top-notch pros with physiques that are above average. Is strength training harmful for tennis players?

A: It’s true, few elite male tennis players posses the muscular physiques often seen in other anaerobic strength endurance sports such as baseball, basketball, football, etc… Even more perplexing, some top female tennis players, such as Venus Williams do possess superior levels of muscularity compared to their male counterparts. Is there an ideal level of hypertrophy for male or female tennis players? I don’t think so. I suspect that tennis, the quintessential gentleman’s sport, may have dodged the not so gentlemanly iron a little longer than other sports and is just now catching on. There’s no reason that strength training would improve physical capacity in other games but not in racquet sports.

Michael Chang, who champions the case study supporting strength training with his well-developed lower body, developed a hard-hitting baseline game despite a lack of advantageous height. Tennis requires high levels of starting strength, agility, strength endurance, and flexibility. All of these qualities improve with a properly executed strength training program. Let’s look at them one by one:

Starting Strength

Starting strength, or the ability to recruit as many motor units (all the muscle fibers controlled by one motor nerve) as possible in an instant is required from the first swing of the racquet. It is technically considered a component of speed strength.

It should be obvious that 80-140 MPH serves and furious sprints to the ball are not performed without quickly accessing high-threshold motor units. Of course, muscle fibers usually remain somewhat dormant until presented with tension that “recruits” them in order to overcome the resistance. This challenge can easily be provided in the form of a well-designed resistance training program. Once the motor units have been trained, it becomes much easier to access them for tasks that require acceleration against small resistances, i.e., the racquet.

Explosive Strength

Explosive strength is the ability to keep muscle fibers activated once they have been innervated – it is the second component of speed strength. Explosive strength is required for sprinting after a return, or generally, any rapid accelerative movements. This presents the most obvious need for strength training which can be developed in the weight room very easily and safely.

Remember not to mistake strength training with bodybuilding. The development of force can be greatly increased without significant gains in mass. Athletes are recognizing the need for strength training in tennis at a very rapid rate.

Agility

Agility is the ability to integrate starting strength, explosive strength, and balance within a single movement or movement pattern. A common tactic employed in tennis is to physically and neurally exhaust an opponent by constantly firing cross-court shots, forcing repeated and rapid directional changes, debilitating the opponent¹s energy stores and strength levels.

Because it is a complex quality, agility is a trainable characteristic. A strength training program won’t make a player look like Flex Wheeler, but the improvement in agility will save him in the late sets.

Strength Endurance

This is the ability to perform sub-maximal efforts over a duration of time. Tennis matches often endure for four or more hours. Increased levels of maximal strength provide a strength reserve so that, for example, repetitive tasks which used to require say, 21% of a player’s maximal strength might now require 17% of maximal strength. This is what improves the player¹s ability to remain effective for a longer period of time.

Flexibility

A great concern among tennis coaches and players is that resistance training will decrease an athlete’s range of motion (ROM). Although resistance training without stretching might limit an athlete’s ROM, performing regular stretching exercises will prevent a loss of flexibility.

Although many athletes believe they are better or healthier athletes when they are more flexible, there is such a thing as too much flexibility. Limit your flexibility training to ROM development specific to performing your sport, with a bit of room to spare for unforeseen events, such as slipping into a partial split position as you reach for a long ball. Two things scare me (and Austin Powers): nuclear weapons and carnies! Please don’t show me your contortionist act, save it for the circus.

Q: Charles, “Lower it slow and under control” is a mantra among experienced trainers in the gym. So I was surprised at a seminar last weekend to hear Dr. Fred Hatfield say he would de-emphasize the eccentric portion of his squats in preparation for personal records. Is that really effective?

A: Unlike many old axioms, this one has a certain logic. The conventional wisdom is that we possess more eccentric strength than concentric strength. In other words, we can lower more weight down than we can lift. Thus, we can sometimes get more “bang for the buck” during the eccentric phase by extending it’s duration during any given repetition. So why is Dr. Hatfield talking about lifting at speeds that are commonly considered ineffective?

Here’s why: whether your primary training objective is mass or strength, you should spend time devoted to each respective quality, since each depends upon the other. During periods devoted to hypertrophy development, a certain duration, or time under tension, is necessary to force metabolic adaptations. This duration varies from person to person, but generally is between twenty seconds to a minute per set.

When strength is the quality you wish to target with your training, heavy loads must be employed which are more taxing on the nervous system than the musculoskeletal system. With this type of training (heavy weights and low reps), the goal is to take advantage of the stretch-shortening cycle (the elastic component of the musculo-tendonous system) through a controlled, but rather fast decent, and then to accelerate through the sticking point of the lift on the concentric phase. Slow descents tend to dissipate the kinetic energy which becomes stored in the tendons during the eccentric phase.

Incidentally, Fred Hatfield practices what he preaches. Watch a video of his 1014 pound squat. He lowers this almost unimaginable load with little visible caution ( current powerlifting star Shane Hammond, the youngest athlete ever to squat 1000 pounds, also employs the “dive bomb” technique). For a strength athlete there are two distinct benefits of learning to implement a faster eccentric – allowing a greater training load increases the amount of available motor units as mentioned above. Also, the athlete can develop a greater stretch-shortening cycle which I alluded to above. Though this outwardly sounds deleterious, we have to remember that the tendons also need to be exposed to tension in order for them to adapt to training in conjunction with muscle.

There is a time for slower lifts and a time for faster lifts. Bodybuilders and weightlifters alike should use both, deciding where to spend the majority of their time based on their sport. A bodybuilder may spend two weeks lifting heavier loads with a fast tempos for every four weeks of using lesser intensity with a slower tempo. A weightlifter might benefit more from two weeks of lower intensity with faster tempo for every four weeks of greater intensity with a faster tempo.

Q: Mr. Staley, I usually spend the last four weeks of power meet preparation pyramiding up to my 1RM’s in every workout. Do you think I should use some static sets as a change of pace?

If you are always breaking PR’s in competition I would stay the course and only break out the pyramids for those last four weeks. Since you are looking for a change of pace, I’ll assume that you feel there may be a more effective technique out there for you. I happen to have a neat three weak peaking phase which I often use with Olympic lifters. Here’s I’ll modify that peaking phase for your needs as a powerlifter.

In this cycle, you lift three days a week, and each competitive lift is trained twice each week. The workouts are arranged like this:

Monday Wednesday Friday

Bench Press Squat Bench press

Deadlift Squat

Deadlift

How exactly should you progress? In preparation for lifting competition my athletes focus primarily on singles, performing many attempts that resemble competition lifts. Consistent use of belts, wraps, lifting shirts, and any other supportive gear is strongly encouraged in this final phase. After this phase, allow a full week as a super-compensation/ taper phase before you compete‹ don’t lift at all during this last week.

Here’s a sensible progression of intensity for this peaking phase:

Workout Sets & Reps Intensity (%1RM)

Workout one: 7×1 80%

Workout two: 6×1 82.5%

Workout three: 5×1 85%

Workout four: 4×1 87.5%

Workout five: 3×1 90%

Workout six: 2×1 92.5%

When you first try this peaking cycle, don’t compensate for the lighter than usual load by accelerating faster or slower than you would perform with maximal loads, just try to simulate the speed you anticipate using at 100%. If the percentage doesn’t come out to a round number, simply round up or down (depending on how you feel that day) to the closest loadable weight.

Lastly, I am a big fan of using brief rests between sets – usually between 1.5 and 2 minutes, which we time on a stopwatch. These shorter rests have been shown to improve relative strength, and they also create a sense of urgency – you really don’t have time to let your mind wander between lifts.

Give this a try and e-mail me with your results!

About the author

Prominent in the United States and many other countries, Charles is recognized as a authoritative coach and innovator in the field. His knowledge, skills and reputation have lead to appearances on NBC’s The TODAY Show and The CBS Early Show, along with many radio appearances. He has written over a thousand articles for major publications and online websites in the industry.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.