Charles, My mother just turned 70 years old. She has been sedentary all of her life and seems to be paying for it now, exerting great effort just to get out of her recliner. Is it just too late to start figuring out how to strengthen her body at her age? Any suggestions to reverse this trend would be greatly appreciated and could potentially improve the quality of my mothers life.

Look at the bright side. From what you’re telling me, your mother does not seem to have any debilitating musculoskeletal or neural disease and can still climb out of that recliner. She needs to start squatting!

When we think of squatting, we usually think of an Olympic bar with dozens of 45 pound plates loaded on it, hoisted by belted, mummified giants who can barely be seen through the cloud of chalk they are training in. That’s not what we are talking about here. I have outlined a progressive plan to strengthen and stabilize your mother’s knees while increasing her range of motion slowly so that she can meet and maintain the daily challenges of her lifestyle.

According to Dr. Paavo Komi, lean body mass decreases on average about 30% between the age of 30 to 70, and strength erodes at a parallel rate. Much of that loss of mass and strength is in the lower body. According to Dr. Sal Arria, the debilitating effects attributed to aging can arise from disuse more often than actual disease. The muscles trained in a squat are the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gluteals— all essential in normal daily activities such as walking, stair climbing, and getting into and out of a seated position. Whether you compete in triathlons, play golf on the weekends, or just getting off of the couch to answer the doorbell, you’re going to need your legs.

Before explaining how to perform a squat or an exercise derived from a squat, let’s dispel some myths and misconceptions. First of all, the notion that “Squats are bad for your knees and back.” Repetitive tension on a muscle, joint, or connective tissue will accumulate trauma which will culminate in an injury if periods of recuperation are not implemented into the plan; therefore, squatting is not bad for your knees and back, improper frequency is. A second fallacy that has permeated throughout every health club in the country is “Squats are for athletes.” Although athletes do indeed squat, the variations they use usually resemble a position they are likely to find themselves in during the duration of a game or event that they participate in. Much like an athlete, your goal should be to squat in a fashion that will enhance your abilities to meet the requirements of your day to day life and meet them with ease.

Teaching the squat is not terribly complicated— it’s one of the most natural things we do (or should be, in any event). Besides a few postural points and safety tips, it’s a matter of sitting and standing. The real key is finding a progression that will allow us to improve strength and range of motion in stages. Regardless of which progression you have achieved, there are a few universal rules when performing a squat: maintain a straight back and natural lordotic curve (curvature of lumbar spine), keep the head in a neutral position, focusing your eyes on an object at head level in front of you. Avoid allowing the knees to move ahead of the feet. Point your toes slightly outward and make sure your knees remain aligned directly over the feet (i.e., don’t let them drift inward toward each other) throughout the exercise.

Based on the abilities you informed me of, this would be the progression your mom should follow (I’ll describe this as if I was talking to the exerciser) :

Eccentric Squat on Chair: Stand in front of a sturdy chair. Slowly lower yourself down to the chair (3 or 4 second duration) until you contact the chair. Ease into the chair as if you were lowering yourself onto a carton of eggs. Have a partner or trainer assist you out of the chair, returning to a standing position through the same plane of movement as the descent. Perform this movement as long as you can maintain proper form as described earlier. At the first sign of form deterioration, stop and rest. When you can achieve five repetitions for a couple of sets, try eliminating the assistance from your partner.

Squat on Chair: Apply the same principles to this variation; however, with as little momentum as possible, rise from the chair without assistance. Once you feel you have mastered this and can complete four or five sets of five repetitions, see if you can dispense with the chair altogether.

Squat: Athletes call this the “King of Exercises.” Unfortunately, they tend to complicate it so much that you would believe that you have no place trying it! Of course, there are little intricacies and tricks that competitive powerlifters implement when muscling up hundreds of pounds, however, you will never need to use any of these techniques. Even after progressing from eccentric squats on the chair, to squats on a chair, you may surprised how awkward this most common variation feels at first. Lower yourself to a point that your range of motions comfortably allows, never rounding your back, then without ever relaxing return to an upright, standing position. From this point, as you see a need for greater resistance, you can rest a barbell behind your neck, adding weight to the bar as necessary.

The deterioration of the lower body is vicious circle. Loss of strength leads to inactivity, which leads to further losses of strength, and so on. Squatting may be more than a means to maintain a strong lower body, it may be a significant key to maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Charles, over the past 6 months I lost 20 pounds (mostly fat) doing a weight training program that my boyfriend designed for me. I usually do between 5 and 10 reps per set, and between 3-4 sets per exercise every workout. Last week, I met a girl at the gym with the body I want (read “that I would KILL for) and she told me I was going to get bulky (which I think is already happening) if I don’t start paying more attention to aerobics and higher rep exercises. Do you think she’s right, or can I just continue with what I’m already doing?

Please— listen to what you’re saying! YOU LOST 20 POUNDS OF FAT DOING NO AEROBICS! I DON’T SEE WHAT THE PROBLEM IS HERE!

Look, The girl who’s body you covet might be right if you had the same genetic make-up as her, but you don’t. Athletes make the same assumption— that doing the training program of their athletic hero will give them the same results. You cannot refute the preliminary results of your training program…it’s working! Understand that different body types exist and your adaptation to training cannot be exactly the same as someone else’s. Set goals for yourself that are lofty; however, attainable with your God-given attributes. So, keep up the great work— you’re already making better progress than most!

Charles, My question concerns type IIB fiber conversion. I read on your website and other places that trained IIB fibers disappear only to reappear after a layoff. I was wondering how to use this knowledge to plan relative strength training phases. In other words, what is an ideal way to train the IIB’s?

Research shows that our fastest twitch muscle fibers (which scientists categorize as “Type IIb”) cannot be found when studied after periods of strenuous exercise. We don’t really know what happens to them, however, we do know that they reappear after a brief (1-2 week) layoff from training. This raises a question that is certainly controversial in the sport science community: Do we let them significantly recover over a seven to fourteen day period or do we let them stay in hiding and just maximize the efficiency of the muscle fibers that have weathered the storm?

Incidentally, I dislike the use of the traditional classification system which classifies all motor units into three categories. When performing a muscle biopsy, we see a very wide and varied spectrum of fibers of differing twitch rates, mitochondrial densities, diameters, and so on. What I’m saying is that you cannot distinguish between different types of motor units as easily as you would your left and right arm.

High tension efforts are the only way to access and train your high threshold motor units. Much like the axiom “you cannot wait until everything is just right in your life,” you cannot wait until you are sure that every muscle fiber in your body has recovered before you perform your next workout. As a rule of thumb, try training the fast twitch- dominant muscle groups (i.e. pecs, lats, gastrocs and hamstrings) once a week. This should allow sufficient recovery. For some of the slower-twitch muscle groups (i.e. biceps, triceps, deltoids, and soleus) train twice a week because slow twitch muscles tend to have a higher tolerance to exercise.

Make sure you track your progress, incidentally. If you are not progressing from one workout to the next in some measurable way then you have either adapted to your training stimulus or are not sufficiently recovered.

Charles, Do you recommend O.K.G. ?

No.

Charles, I have a quick question for you. I am the fitness director at a local gym in my town. One of the trainers on my staff was putting together a program for one of her female clients. Her approach was to intentionally overtrain her or in her words, “To break down some of the muscle” that this women had developed through rowing in college. Apparently this client wasn’t happy with her “rowing” build anymore. She wanted a more sleek and slender look. Is there any merit to training somebody like this? My gut feeling is to say no. The trainer was basically going to train this client’s more developed muscles everyday. Wouldn’t this approach just put her into a catabolic state? Your insight into this matter would be greatly appreciated.

Oh yes, I love the idea of deliberately breaking down muscle! After all, it’s only good for elevating your metabolic rate and improving your functional capacity. So by all means, let’s get rid of it. Incidentally, I have a great nutritional plan that you can integrate with your training plan, which I first learned from a TV special called “Into Thin Air: The Tracy Gold Story.” Basically, there are two possible approaches: either eat whatever you want, and then perform reverse peristalsis soon thereafter (don’t give up after the first few times— you’ll learn to tolerate it eventually!), or, just learn to live without those pesky calories in the first place. The downside is that all your friends and relatives will become concerned with your “extreme” dietary habits, but few people can really understand what it takes to be a serious athlete, as I always say.

Sarcasm aside, I must make it clear that it is unconscionable for a health care professional (which includes professional trainers) to contribute to deconditioning a client, even if that client instructs the trainer to do so. If such a case was presented to the International Sports Science Association, the trainer in question would be reviewed by a board of directors for possible revocation.

Charles, there’s an audible click in my left shoulder when I perform military presses. It doesn’t cause any pain— it’s really more annoying than anything. Should I be concerned about this?

Although you are not experiencing pain (yet), your body is sending a message. The click is indicative of a problem (certainly one that couldn’t be diagnosed online), and is possibly precursory to something down the line. My recommendation is first have it checked by a qualified orthopedist so that you can develop some sense of what is going on. In the mean time, modify the angle and/or plane you press from in such a way that the click does not happen.

Dear Charles, I am a 26 year old who has been powerlifting since I was 18, but recently I changed over to Olympic lifting. I had a coach for a while but since my car doesn’t do long distances, I had to give that up as well. I have a local health club that I can get to and was wondering how combine training for both sports since I like them both. I know there will be a compromise in performance in all my lifts. When I make an attempt at one or the other then I will specialize instead of compromise. But being that I can’t make up my mind and want to do both I was wondering if you had any suggestions.

I recall touching on a similar question previously in Mesomorphosis. I apologize if there is any redundancy in my answer; however, it’s such a good question and I would like to reemphasize how well powerlifting and Olympic-style weightlifting synergistically mesh.

Here’s a thought: How about throwing a little bodybuilding into the mix also? There is a relationship between absolute strength improvement and hypertrophy, so as long as you are not trapped at the very top of a weight class, I would make a little time emphasizing hypertrophy. Here’s how I would approach a nine week macrocycle that improves muscular development, speed strength, and absolute strength. (For clarification of the various qualities of strength, read my article on speed strength in the December issue of Mesomorphosis).

Spend the first three weeks of the mesocycle on hypertrophy. There is no argument in strength sports that bigger stronger muscles are preferable— the benefits are obvious. In this phase, train 3-4 days per week, using 3-4sets of between 6-8 repetitions per exercise. I recommend no more than four exercises per workout in this phase. It would be preferable to perform exercises that bear little or no resemblance to the competitive lifts you are training for.

After three weeks of muscle mass development, it’s time for you to make that muscle work for you. The way you’re going to do this is by increasing your lifting intensely. This is a perfect time to implement the three power lifts. I recommend performing one of the power lifts on three evenly spaced days throughout the week (i.e., bench on Monday, squat on Wednesday, and deadlift on Friday). Start of with 3-4 sets of between 2-3 reps per set. and gradually “ramp up” to one rep maximum attempts by week three. By now your body will definitely ready for a break from this mesocycle!

Having developed a foundation of hypertrophy and “peaked” that foundation by improving your maximal strength, now’s the perfect time to implement the Olympic lifts. I recommend slightly higher training frequency for the Olympic lifts because of the decreased intensity forced by the heightened skill element. For three successive weeks, perform snatches and front squats on Mondays, cleans and snatch pulls on Wednesdays, and finally, the competitive snatch and clean & jerk on Fridays.

I would be surprised if you could actually perform this schedule without making at least minor adjustments. Instincts are an essential trait that you will need to bring these competitive lifts to a high level, so don’t be afraid to make modifications to any suggestions that I make!

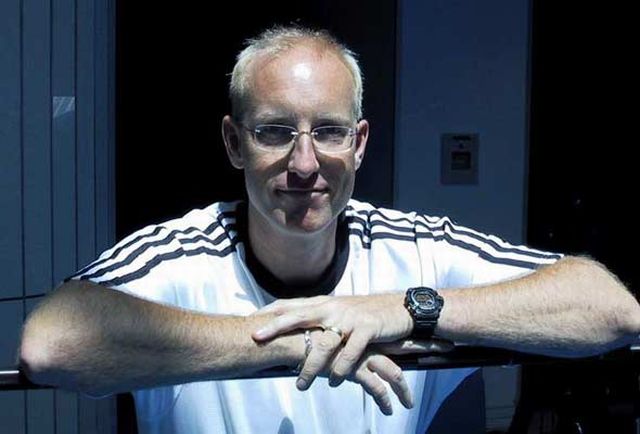

About the author

Prominent in the United States and many other countries, Charles is recognized as a authoritative coach and innovator in the field. His knowledge, skills and reputation have lead to appearances on NBC’s The TODAY Show and The CBS Early Show, along with many radio appearances. He has written over a thousand articles for major publications and online websites in the industry.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.