Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

Table of contents

Introduction

What’s your first thought when you hear that someone was arrested for practicing medicine without a license? For me, the term always conjured images of a doctor, disgraced and with a revoked license, pulling bullets out of mobsters in a dirty apartment. Or someone doing bootleg Botox. Maybe a doctor who practices in the United States but earned his M.D. in Belize (Tony Bosch, I’m looking at you). Sometimes I think of the guys who get caught injecting silicone into butts in a strip mall (Florida, I’m looking at you). I don’t know if half of those examples qualify, legal speaking, as “practicing medicine without a license.” But given the recent spate of deaths in bodybuilding, it got me to wondering. Could a precontest coach be charged with practicing medicine without a license? I think the answer is yes. I also think there are a few reasons we haven’t seen it… yet.

Bodybuilding in the big league

The most prestigious bodybuilding contest in the world is over and defending two-time Mr. Olympia Mohammed “Big Ramy” Elssbiay failed to repeat. Hadi Choopan is now the current Mr. Olympia. To the untrained eye, which is anyone who doesn’t follow the pseudo-sport of bodybuilding, most of his competitors looked about the same — unbelievably huge and ripped. Most people have never seen, nor will ever even be in the same room as, anyone their size. But I’ve been in plenty. I’ve earned my living in those rooms.

The stakes are high at the professional level. Contracts may have bonuses for wins or top placings, not to mention the contest winnings at the highest level represent a huge chunk of a bodybuilder’s annual income. Mess up and you might have another contest in a week and several over the next month – or at the very top level, you might be waiting a whole year for redemption. Contrast this with sports that have a season, where you might play badly in one game, then redeem yourself the next night or weekend – and you see why so much is riding on such a brief window.

Because I’ve been part of this industry, I can tell you with certainty that drugs are not a shortcut to these physiques. That would be like saying in 1969 that taking Apollo 11 was a shortcut to the Moon. It’s not a shortcut if it’s the only way to get there. But bodybuilders don’t have NASA planning their route, they have so-called “precontest coaches.”

Precontest “Coaches”

Precontest coaches, alternately and euphemistically called diet coaches, prep coaches, precontest/prep gurus, or less euphemistically “anabolic coaches” and “drug coaches,” are in the business of telling their clients what drugs to take, and when to take them. They are often responsible for diet and cardio as well, and sometimes (less often) the actual weight-training workouts of their clients. I cringe at calling most of these people “coaches” at all, but for the purpose of this article, that’s what we’re stuck with. At the highest levels they might also provide year-round diet and training routines. This depends on the client, their goals, and how famous the client already is. A competitor who consistently earns a top 10 placing at major contests will get more attention from their coach, who stands to gain far more from their success than clients who aren’t winning. Clients without major wins and a social media following will often get cookie-cutter programs and minimal contact with the coach. Sometimes the coach’s assistant writes out the program entirely.

I’ve seen coaches charge anywhere from a few hundred dollars per month to half the competitors’ winnings to… well to men who coach female bikini or wellness competitors for “free.” Publicly most of these coaches aren’t exactly honest about their services. A very famous coach from Canada once bragged in an online interview (on a website which counted me among their regular authors) that he didn’t see the need for extensive drug use for female clients. Privately, and concurrently, one of his fitness competitors complained to me about his overuse of thyroid medication in her cycle and shared her fear that he was wrecking her metabolism permanently. Another coach, (in)famous for DNP (dinitrophenol) use in clients, denies this entirely. Most of these coaches are lying half the time and not telling the whole truth for the other half.

Clients who are legitimate contenders for major contest wins will get weekly advice all year, and daily advice in the weeks before a contest. When you look at a coach’s website and you see a ton of success stories, you need to realize that there are far more clients not taking home trophies, but those seventh-place amateur placings with the cookie cutter programs don’t usually make the landing page. Don’t worry though, once a (previously ignored) client gets a major victory, their coach will rewrite history to tell everyone how involved he was in the client’s victory. They worked hand-in-hand, you see, from the very beginning.

What makes this so dangerous?

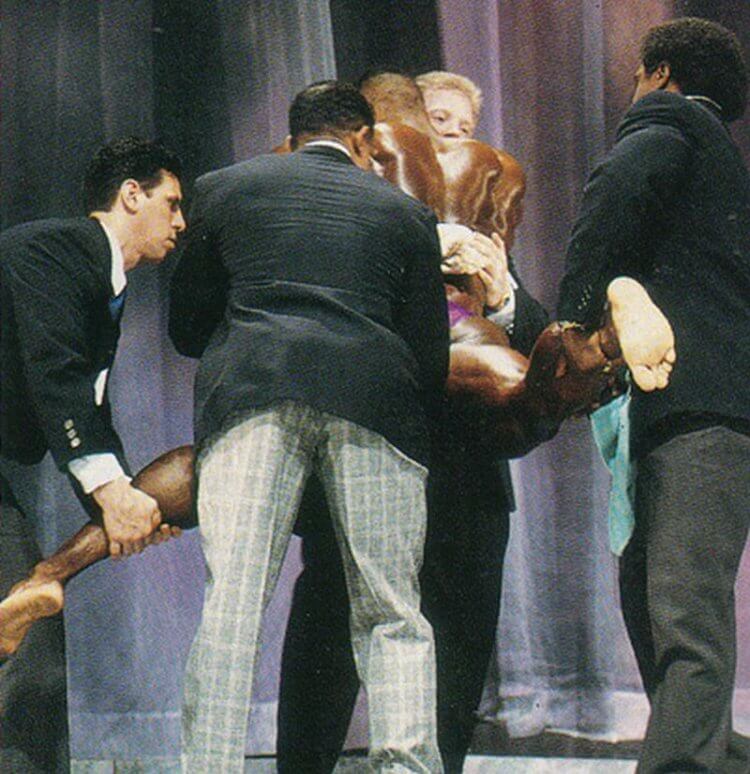

For personal trainers, its often the case that their bodies are their business card. But for prep coaches, their clients’ bodies are literal walking advertisements. When they can walk, that is. Professional bodybuilder Paul Dillet at the 1994 Arnold Classic cramped so badly on stage that he had to be carried off, stiff as a mannequin, one man taking each of his limbs. The culprit? Diuretics. To his credit, his coach (a friend of mine) has never shirked responsibility for that incident.

Dillet fared better than bodybuilder Mohammed “Momo” Benaziza, an IFBB bodybuilder who in 1992 died of a heart attack in his hotel room on the night of a contest. He’d been projectile vomiting backstage at the contest and continued for hours afterwards. At the point where he was barely able to walk, fellow competitors called a doctor. By the time medical help arrived it was too late. The death was caused by a heart attack attributed to diuretic use. Again, the point here is that we are talking about consequences that manifest within hours, not months. And we are talking about contests that could represent a third (or more) of a bodybuilder’s annual income. The risk and reward is high by any measure.

Diuretics have long been considered the most dangerous (physique-enhancing) category of drugs in bodybuilding. Steroid abuse may cause some problems in the long term (and at the professional level, there is no use, only abuse). But screw up with diuretics and you’ll be dead within hours. Often diuretics are introduced to a bodybuilder on the day of the show, and this is often after sodium and water has been manipulated.

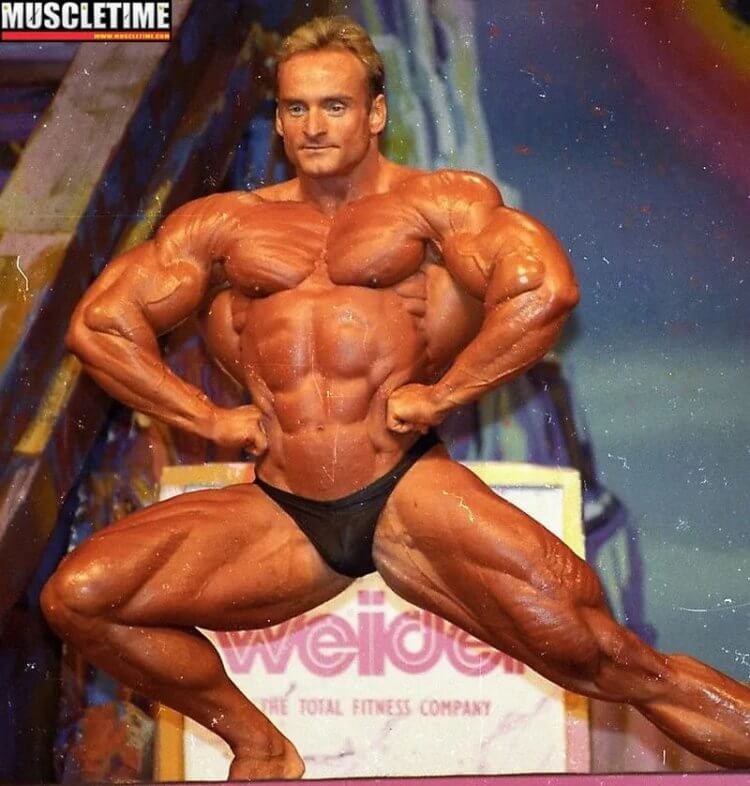

Rarely, do we see this window extended, but it’s been known to happen. Professional Bodybuilder Andreas Munzer died of simultaneous multiple organ failure less than one week after competing on March 6th and 9th, 1996 – after months of complaining that his organs were hurting. But note that this window is essentially the same a major contest having weigh-ins on Thursday or Friday and final posedowns on Saturday. It seems clear that the back-to-back competitions represented a tipping point in Munzer’s declining health, and even though he was admitted to the hospital by the 12th, it was too late.

The window to win the Mr. Olympia title (or any bodybuilding contest) is measured in dangerous hours. At most, it can take a full weekend from weigh ins to winning (or not). Part of a precontest coach’s job is to peak the bodybuilder – to maximize their muscle fullness and size –while simultaneously eliminating all visible fat. And after all of the fat is gone, the water has to go also. That’s where water and sodium manipulation comes into play, eventually giving way to diuretic use – right when the client is at their weakest and most depleted.

But that window isn’t the only time a client can die. Milos Sarcev, who is both an IFBB professional bodybuilder and coach, almost killed himself with an errant injection of synthol (yes, a single misplaced injection almost killed him). The fact that synthol is one of a handful of drugs that can kill with a single injection (insulin, also widely used by bodybuilders, is another). In 2021 a competitor died in his Florida hotel room, and in the preceding and following years we’ve seen multiple bodybuilders die while at home, not in any stage of contest prep, but still while guided by their coaches.

One very popular precontest coach has made his name bragging about all of the carbs his clients get to eat while getting shredded. He’s also well known in the industry for his use of DNP (dinitrophenol), an oral fat burner and mitochondrial uncoupler that can kill with a single overdose. When you consider the fact that precontest coaches regularly advise clients on the use of drugs that can kill with a single injection, the idea of a coach being criminally prosecuted doesn’t seem far-fetched.

What is “Practicing Medicine Without a License”?

Each state has their own version of practicing medicine without a license. Typically, the statute defined the unlicensed practice of medicine as, when an unlicensed person, tries to diagnose or cure an illness or injury, prescribes drugs, performs surgery (or medical treatments), dispenses medical advice, or claims he or she is a doctor. No precontest coaches are claiming to be medical doctors (to my knowledge), so that’s not going to be an issue. Some might dubiously claim a “premed” background, but that means they’re just a college dropout (which is fine — but calling yourself a “premed” dropout is nonsensical). And it might be a stretch to claim that anyone is diagnosing or curing anything, so that doesn’t feel relevant.

But as precontest coaches tell their clients what drugs to take, it might be the case that this could fall under the category of “prescribing” drugs. This is an awkward fit. Is telling someone to take specific drugs at specific doses “prescribing” them? I think that’s a stretch and I can’t find anything to support that definition, standing alone. So that’s probably off the table in terms of a successful prosecution.

The most likely way a coach could be charged with practicing medicine without a license, is through dispensing medical advice. I spoke to a couple of attorneys about this theory and there’s a consensus that it’s viable. “Dispensing medical advice” is the vaguest part of most statutes (giving prosecutors the most potential latitude) but paradoxically seems to be the most difficult verbiage under which to secure a conviction (based on an admittedly cursory review of cases). In most circumstances it might be nearly impossible to prove that the average defendant was dispensing medical advice. But not with precontest coaches.

Admittedly, I’ve known circumspect prep coaches who refuse to put anything in writing (besides training and diet), but this is the exception rather than the rule. A significant paper trail (emails, texts, etc. with fully outlined cycles, drugs, doses, timing) would almost certainly exist in most cases. Giving someone paid advice on which controlled substances they should obtain and use to achieve specific off-label goals, is certainly illegal under numerous statutes, but our primary question today is whether it’s practicing medicine without a license. It may be, but it’s wholly possible that we don’t see it prosecuted under those terms because it’s not worth the additional effort.

Here are three reasons why:

- There are other ways to get a conviction.

In many instances, contest prep coaches are otherwise employed, and the coaching is just one part of their revenue streams; they might be columnists for a bodybuilding magazine, or host a podcast, work for (or own) a supplement company, or…support themselves by doing something less legal. For example, more than one contest prep coach has owned a peptide and research chemical company. At the risk of shocking you, Dear Reader, some contest prep coaches have even been known to…sell anabolic steroids and other drugs. Although it may be the case that they’re prosecutable under the “medical advice” theory outlined above, it’s often not going to be necessary. There are numerous slam-dunk ways to charge any precontest coach, so why bother with a charge that may be a little trickier?

- Nobody cares.

I believe a case can be made that precontest coaches are chargeable as outlined above, there are other reasons (I assume) prosecutors aren’t jumping at the opportunity to take one down. In much the same way that we don’t see outrage at the rampant and unconcealed use of anabolic steroids in bodybuilding competitions. Professional bodybuilding has never had meaningful drug testing. When Vince McMahon started a professional league to rival the IFBB, promoting it as steroid free, the IFBB sought to match their new competition. A semi-legitimate effort was made to drug test competitors at the Arnold Classic in 1990, resulting in four of the thirteen competitors testing positive. Later that same year, at the Mr. Olympia contest, five out of twenty athletes tested positive. After the show, one of the IFBB’s contest promoters, was approached by attendees expressing disappointment at the physiques on display and expressing opposition to continued drug testing. McMahon’s new organization, despite poaching a dozen professionals from the IFBB, never produced the types of (drug-fueled) physiques needed to be competitive and failed to get off the ground. With the IFBB’s competition now gone, so was drug testing.

This past October when the International Federation of Bodybuilders (IFBB) was cited and sanctioned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) for non-compliance with the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC), eyebrows weren’t exactly raised. Almost nobody in the bodybuilding media covered (or even noticed) WADA’s proclamation. News wire service Reuters shrugged it off with a few inches of uninspired text. This year, the World Cup — soccer if you’re from the U.S., football if you’re from anywhere else – finished on the same weekend as the Mr. Olympia. While the former produced billions of dollars in revenue, the latter reportedly lost money; note that it’s been less than a week since the contest at the time of this writing, so the accounting may change, but currently I’m being told that the losses are in the millions of dollars. Bodybuilding is so unpopular that the most prestigious contest in the world is reportedly operating at a loss. This means that even a major bust (relative to bodybuilding) is objectively going to involve a bunch of nobodies. This is an unappealing bust compared to going after a coach or athlete involve in the Big Four (or really any sport with a legitimate professional league). And while not all prosecutors care about “big game hunting” (going after famous or big-time defendants), it would be foolish to believe that this doesn’t often factor into what cases get opened.

- The victims can’t (or won’t) report the perpetrator.

One of the attorneys with whom I spoke, suggested that most prosecutions involving the unlicensed practice of medicine will typically involve at least one other aggravating factor. This is what I think also. Most cases I reviewed weren’t simply someone giving drug advice. Often there was an element of fraud (typically claiming to be a doctor) and physical injury (because the patient is usually the one reporting the incident to the police). This is great news for every pothead, ever, who’s cornered someone at a party to talk about what strain of weed they should smoke to relieve anxiety or sleep or…whatever, man. It’s also great news for precontest coaches, because the client can’t report their coach without admitting that they themselves broke a ton of laws and turning over a huge cache of personally incriminating evidence.

Yes or no?

So in the end, I believe it’s highly probable that a precontest coach can be successfully prosecuted under specific circumstances, with appropriate evidence, on a charge of practicing medicine without a license. But I also believe there to be many reasons we are unlikely to see those charges filed any time soon.

About the author

Anthony Roberts is an expert in the field of performance and image enhancing drugs. He has authored books ranging from the pharmacology of anabolic steroids and growth hormone to their illicit use and trafficking. His writing can be found in magazines such as Muscle Evolution, Muscle & Fitness, Human Enhancement Drugs, Muscle Insider, and Muscular Development.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.