Currently the only approved treatments for hypogonadism or testosterone deficiency are testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) therapy. Of the two, TRT is definitely the one most commonly prescribed. One of the reasons is that hCG is ineffective in primary hypogonadism—a type of hypogonadism in which testicular failure is the culprit. This would exclude around 15% of cases with testosterone deficiency [1]. Other reasons can be that hCG requires frequent injections (commonly three times a week) and is more expensive than certain TRT alternatives.

A central issue with TRT is that it suppresses spermatogenesis and therefore leads to infertility in a substantial number of men. Additionally, testicular size decreases. For men who therefore wish to preserve fertility and testicular size, TRT is obviously a less than ideal candidate. While this is less important for older men who are eligible for TRT, as they are less likely to have plans for having kids, it is an important issue for young men who wish to treat their hypogonadism.

As discussed in my previous article Anabolic Steroids and Fertility, testosterone suppresses the secretion of LH and FSH, consequently, spermatogenesis is inhibited. Part of this suppression is mediated by the conversion of testosterone in estradiol. One could, therefore, increase testosterone levels by negating this suppressive effect of estradiol on the hypothalamus and pituitary. Indeed, use of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs)—which exert antagonist action on the estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus and pituitary—leads to a robust increase in LH, FSH and testosterone in men with secondary hypogonadism [2]. Similarly, use of aromatase inhibitors—which prevents testosterone from being converted to estradiol by the action of the aromatase enzyme—also leads to increases in LH, FSH and testosterone in these men [3]. A consequence of this is that spermatogenesis can be preserved.

Wouldn’t it be an ideal form of treatment for secondary hypogonadism if this turned out to be efficacious and safe?

Enclomiphene as a treatment for secondary hypogonadism?

Indeed it would be an ideal form of treatment if that would be true. As such, a pharmaceutical company, Repros Therapeutics Inc., made an attempt at making a SERM approved by the FDA for the treatment of secondary hypogonadism. Before I continue about how this process went, I’d like to provide some background on their SERM: enclomiphene citrate (brand name Androxal, later rebranded to EnCyzix).

In the 1960s, a drug named clomiphene citrate was found to induce ovulation. As such, it could be used as a treatment modality to promote fertility in anovulation or oligoovulation. Back in the day, it was already known clomiphene worked through increasing the release of gonadotropins (LH & FSH) [4]. For this reason, researchers also started to evaluate its effect in men on spermatogenesis and testosterone. In the decades to come, a lot of trials have demonstrated its efficacy in stimulating testosterone production in hypogonadal men. However, clomiphene has not been approved by the FDA for the treatment of hypogonadism. Nevertheless, it’s prescribed off-label for this indication, and the 2018 guideline for the evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency by the American Urological Association conditionally supports its use as an alternative to TRT [5].

An issue related to clomiphene treatment is that, despite robustly increasing testosterone levels, the data of its effect on symptom relief of hypogonadism is conflicting [6]. Large scale good-quality trials might clarify these matters and perhaps shed a light on which patients might benefit the most from its usage. Given that the drug’s patent expired ages ago and generics are being manufactured, it’s not so attractive for pharmaceutical companies to invest in it. So these trials might never ensue.

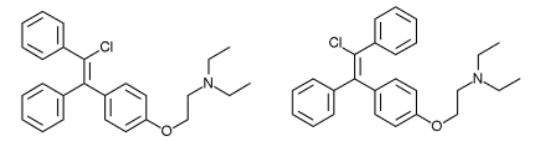

As is the case for a lot of drugs, clomiphene is a racemic mixture. Which means as much as that it consists of a “left-handed” and “right-handed” type of the molecule. Typically only one of these stereoisomers, as it’s called, is the active compound. Which is the result of a better fit with the receptor it acts on. Much like how a glove only fits one of your hands and not the other, the “left-hand” type is more effective in binding to a “left-hand” receptor than the “right-hand” stereoisomer. Clomiphene consists of the stereoisomers zuclomiphene (pictured on the left) and, you’ve guessed it, enclomiphene (pictured on the right):

In general, zuclomiphene is viewed as functioning as an estrogen receptor agonist, whereas enclomiphene is viewed as a potent estrogen antagonist [7]. Enclomiphene can therefore be viewed as the active stereoisomer of clomiphene. The idea of enclomiphene, thus, is that you have something that might be more effective and safer than clomiphene. Although I guess the most important aspect is that Repros Therapeutics Inc. could patent its therapeutic use for the treatment of male hypogonadism.

Clinical data on enclomiphene

In order to apply for FDA approval, the pharmaceutical company had to conduct some clinical trials. The first published trial only included 12 men and was unblinded in nature [8]. Meaning, both the participants and researchers knew which treatment the men were receiving. The participants were men with secondary hypogonadism treated previously with topical testosterone. They were randomized to either receive topical testosterone again or enclomiphene (25 mg daily).

After six months of treatment, testosterone levels were practically the same between the groups: 545 ng/dL (18.9 nmol/L) in the group receiving the gel and 525 ng/dL (18.2 nmol/L) in the group receiving enclomiphene. Free testosterone levels went up too and were also virtually the same between the groups. Additionally, and of course, sperm count was suppressed in the men receiving testosterone with numbers around the 20 million/mL. And also as expected: sperm count was up in the men receiving enclomiphene, with an average around 150 million/mL.

A couple of subsequent clinical trials were conducted. Perhaps the most interesting was one published in 2016, which was aimed at obese hypogonadal men [9]. The paper encompasses two parallel randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trials. Now that’s a mouth full, and I think the term ‘double-dummy’ requires some explanation. In the earlier trial I covered, I mentioned it being unblinded in nature. So the participants and researchers knew what treatment each subject was receiving. Commonly, when comparing two different medications, you can simply blind the subjects (and researchers) by giving the groups identical capsules, or tabs, or whatever. However, testosterone gel is a gel, and enclomiphene is a tab that you need to swallow. So you can’t do that. In order to thus make a trial like this blinded, you need to give both groups both tabs and a gel. So one group receives a placebo gel and enclomiphene, and the other group receives testosterone gel and a placebo tab. Aka, double-dummy. (And because the trial was placebo-controlled, one group received a placebo gel and placebo tab.)

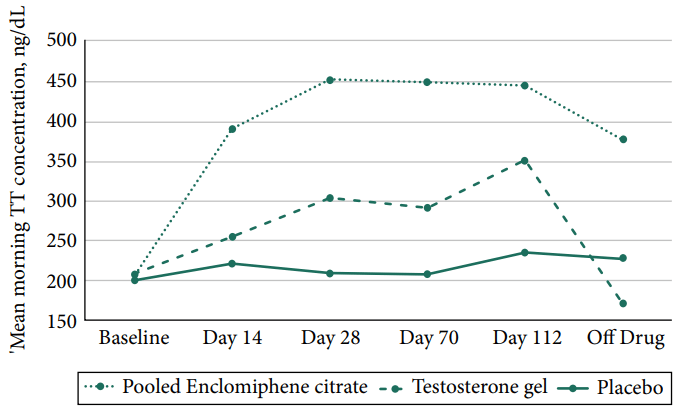

The two trials described in this paper used the same protocol, and what was perhaps most interesting was the sample size: 256 subjects in total! That’s finally getting somewhere. The intervention lasted 16 weeks, and subjects in the enclomiphene group received 12.5 mg daily and were titrated up to 25 mg daily if testosterone levels hadn’t increased to at least 450 ng/dL (15.6 nmol/L) at week 4. The up-titration was done for half the subjects receiving enclomiphene. Now this is where things start to be interesting: although half the subjects got titrated up at week 4, absolutely nothing happened with the mean testosterone concentration:

And, indeed, at the end of the intervention, the group mean was just slightly below the 450 ng/dL (15.6 nmol/L) cut-off for up-titration still. Finally, 29 of the 85 men in the enclomiphene group didn’t see their testosterone rise above the hypogonadism cutoff value of 300 ng/dL (10.4 nmol/L) after 16 weeks of treatment. Additionally, the researchers did a HORRIBLE JOB at getting the testosterone gel group treated properly, as can be seen by the mean testosterone concentration of that group. Almost as if they did it deliberately so the enclomiphene group would do better on some measurements… (while it’s a double-dummy study, you can still instruct your patients improperly with the gel application.)

Importantly, the only endpoints were testosterone, LH, and FSH levels, and sperm concentration. Clinically relevant endpoints, such as sexual desire, erectile function, fatigue/vitality, etc. were not investigated. Seemingly also not in the other (published) trials. Or, perhaps, they were investigated, but simply never reported in the study results because the results were disappointing. And I think it might’ve been the latter, as the FDA did not approve the drug for the treatment of secondary hypogonadism, because there was a lack of measurable symptomatic improvement [10]. The EU equivalent of the FDA, the EMA, also refused the marketing authorisation for enclomiphene some time later, with similar concerns:

“The CHMP [Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use] noted that although the studies showed an increase in testosterone levels with EnCyzix [enclomiphene], they did not look at whether EnCyzix would improve symptoms such as bone strength, weight gain, impotence and libido. In addition, there is a risk of venous thromboembolism (problems due to the formation of blood clots in the veins) with the medicine.”

And clomiphene actually shows very similar results, even mg per mg, as enclomiphene. I’m not gonna summarize the entire literature of clomiphene here, but take for example a trial by Katz et al. in which 86 young hypogonadal men received 25 mg or 50 mg every other day for a mean of 19 months and saw total testosterone increase by 152% (from 192 ng/dL to 485 ng/dL) [11]. Notably, their free testosterone increased a whopping 332%. And if we look at a different trial with obese men, testosterone increased by 98% (from 303 ng/dL to 599 ng/dL) at 25 mg daily [12]. In terms of increasing testosterone, enclomiphene does not seem to have an edge over clomiphene (I have been unable to find a head-to-head trial.)

So, unfortunately, there’s still no FDA-approved alternative besides hCG or TRT for treatment of hypogonadism. And with that, hypogonadal men who seek treatment will be bound to injections if they wish to preserve fertility during TRT. Perhaps (current) SERMs are just a dead end, as their estrogen antagonism also counteracts positive effects. Indeed, as Finkelstein et al. elegantly showed, the addition of an aromatase inhibitor to a testosterone gel leads to a negative impact on body fat and sexual function [13].

References

- Tajar, Abdelouahid, et al. “Characteristics of secondary, primary, and compensated hypogonadism in aging men: evidence from the European Male Ageing Study.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 95.4 (2010): 1810-1818.

- Wheeler, Karen M., et al. “Clomiphene citrate for the treatment of hypogonadism.” Sexual medicine reviews 7.2 (2019): 272-276.

- De Ronde, Willem, and Frank H. de Jong. “Aromatase inhibitors in men: effects and therapeutic options.” Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 9.1 (2011): 1-7.

- Jungck, Edwin C., et al. “Effect of clomiphene citrate on spermatogenesis in the human: a preliminary report.” Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 19.3 (1964): 520.

- Mulhall, John P., et al. “Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline.” The Journal of urology 200.2 (2018): 423-432.

- Scovell, Jason M., and Mohit Khera. “Testosterone replacement therapy versus clomiphene citrate in the young hypogonadal male.” European urology focus 4.3 (2018): 321-323.

- Fontenot, Gregory K., Ronald D. Wiehle, and Joseph S. Podolski. “Differential effects of isomers of clomiphene citrate on reproductive tissues in male mice.” BJU Int 117.2 (2016): 344-50.

- Kaminetsky, Jed, et al. “Oral enclomiphene citrate stimulates the endogenous production of testosterone and sperm counts in men with low testosterone: comparison with testosterone gel.” The journal of sexual medicine 10.6 (2013): 1628-1635.

- Kim, Edward D., Andrew McCullough, and Jed Kaminetsky. “Oral enclomiphene citrate raises testosterone and preserves sperm counts in obese hypogonadal men, unlike topical testosterone: restoration instead of replacement.” BJU international 117.4 (2016): 677-685.

- Earl, Joshua A., and Edward D. Kim. “Enclomiphene citrate: A treatment that maintains fertility in men with secondary hypogonadism.” Expert review of endocrinology & metabolism 14.3 (2019): 157-165.

- Katz, Darren J., et al. “Outcomes of clomiphene citrate treatment in young hypogonadal men.” BJU International-British Journal of Urology 110.4 (2012): 573.

- Pelusi, Carla, et al. “Clomiphene citrate effect in obese men with low serum testosterone treated with metformin due to dysmetabolic disorders: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.” PLoS One 12.9 (2017): e0183369.

- Finkelstein, Joel S., et al. “Gonadal steroids and body composition, strength, and sexual function in men.” New England Journal of Medicine 369.11 (2013): 1011-1022.

About the author

Peter Bond is a scientific author with publications on anabolic steroids, the regulation of an important molecular pathway of muscle growth (mTORC1), and the dietary supplement phosphatidic acid. He is the author of several books in Dutch and English, including Book on Steroids and Bond's Dietary Supplements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.