The human body is covered in an awful lot of hairs. Many of them, however, are very short, light-colored, and thin, making them barely noticeable. These hairs are found all over the body, such as on the upper arms, the belly, the chest, etc. These hairs are also known as vellus hairs. The visible hairs, that are pigmented, longer, and thicker, are known as terminal hairs. These can be found on the top of your head—of course. But also in the pubic region, arm pits, legs, and forearms. In (most) men, these hairs are also found on the face, giving them a beard and a moustache. But also on some of the other regions, such as the chest, back, upper arms, etc. Regions where women, commonly, hardly have any terminal hairs.

In this article I’ll present how hirsutism is assessed using something called the Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system. This system is useful to keep track of any changes in hair growth that might result from androgen use. I’ll also discuss what’s seen in research studies where women are given androgens and how this impacts their hair growth. Finally, I’ll glance over some treatment options for anabolic steroid-induced hirsutism.

Hirsutism can be scored/assessed with the Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system

While women generally don’t have visible (terminal) hairs in the ‘male areas’, the situation is different in hirsutism. Under the influence of androgens, some of these vellus hairs turn into terminal hairs. The threshold at which hair growth is considered hirsutism is somewhat of an arbitrary one. The extent to which it occurs can also vary wildly. Hirsutism isn’t just a condition in which a woman suddenly develops a grizzly bear-like hair coat.

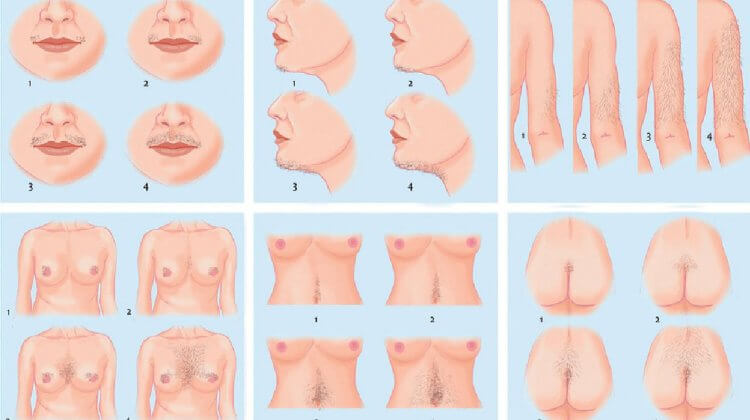

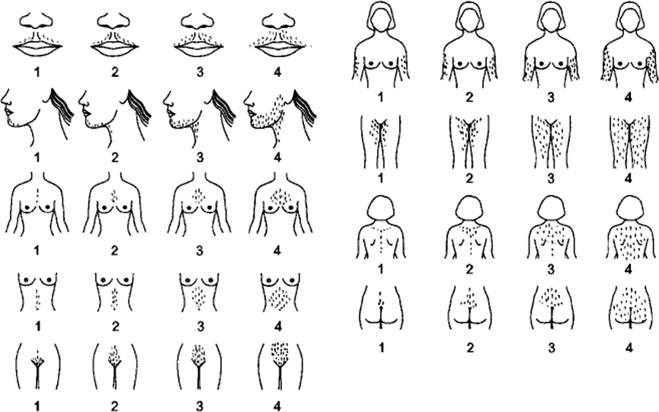

In research, Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system (or actually a modification thereof) is commonly used to assess the degree of hirsutism [1]. It rates the extent of hair growth in 9 body areas, of which each area gets graded from 0 (absence of terminal hairs) to 4 (extensive terminal hair growth). Thus it can yield a score of 0 to 36, with the threshold of hirsutism reached at a score of >6-8 [1]. I should highlight here that the threshold is lower for Far East and South East Asian women, where it’s considered to be hirsutism with a score of 3 or higher [2]. Regardless of these thresholds, a considerable amount of women with androgen excess have scores in the range of 2 to 6, and many women without androgen excess score below 3, and therefore it has also been suggested that a ‘normal’ amount of hair may be lower than 3.

Anyhow, hirsutism is generally considered mild up to a score of 15, moderate from 16 to 25, and severe above 25 [2].

Below is an image in which you can see how this rating system works. It scores the hair growth at the upper lip, chin, breast, upper and lower abdomen, upper arms, thighs, upper and lower back.

Androgens increase hair growth and can cause hirsutism

The link between androgen exposure and hirsutism is an obvious one. It’s the most commonly used clinical diagnostic criterion of androgen excess and most hirsutism cases are caused by it [3]. It should therefore come as no surprise that exogenous administration of anabolic steroids can also induce hirsutism. This might hold especially true for testosterone. This has to do with the local conversion of testosterone into the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). An enzyme called 5α-reductase is responsible for this conversion and is expressed in various tissues, including the skin. This conversion amplifies the effect of testosterone in these tissues expressing 5α-reductase.

The relevance of this is highlighted by clinical trials employing an inhibitor of this enzyme (Finasteride). Women with hirsutism who are given Finasteride show an improvement in their hirsutism [4, 5, 6, 7]. It could be argued that the use of nandrolone might confer a lower risk of developing hirsutism. The reason for this is that nandrolone gets converted by this same enzyme, except not into a more potent androgen but a less potent androgen: dihydronandrolone [DHN] [8]. This has not been directly researched, so this remains speculative but plausible.

In one trial, it was estimated that about 1 in 5 women who received 150 mg testosterone enanthate (plus estradiol) once every month developed mild hirsutism [9]. Herein it manifested itself by an increased growth of hair on the chin or upper lip. The same authors mention that, when the dose is halved, less than 5 % will develop hirsutism. There are some problems with these results, though. For one, they didn’t systematically assess hirsutism, which leaves open some room for bias. Second, once monthly administration of testosterone leads to significant peaks and throughs. It’s not unthinkable that that might affect the risk of hirsutism differently than a similar monthly dose that’s more evenly spread throughout the month.

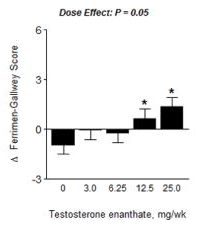

Bhasin’s lab investigated the testosterone dose-response relationship in hysterectomized women with and without oophorectomy [10]. Women were given a placebo, 3, 6.25, 12.5 or 25 mg of testosterone enanthate weekly for 24 weeks. The Ferriman-Gallwey scoring system, as described above, was used to assess hair growth. Significant differences in the Ferriman-Gallwey score were found in the 12.5 and 25 mg groups:

As can be seen, however, the increase was (very) small. Remember: the scale runs from 0 to 36, and an increase of 1 point is pretty small. Thus it appears that, at least up to 25 mg testosterone enanthate weekly, changes in hair growth are minimal when administered up to 24 weeks. An important thing I’d like to highlight, though, is that the onset of hirsutism is quite slow, taking up to 4–6 months [11]. These results could thus definitely be different if this trial was undertaken longer.

And what about higher dosages? Let’s have a look at a study done with female-to-male transsexual patients—after all, this is the only group of patients of which you’ll see (good) clinical trials with high dosages. In a 1986 study, 30 female-to-male transsexual patients received 200 mg testosterone cypionate every 2 weeks [12]. While the authors didn’t accurately assess hair growth (why would they?), they did report that “The increases in amount and coarseness of hair on the chest, abdomen, and facial hair were striking.”. It’s fair to assume that this would’ve been more than just a 1-point increase in the Ferriman-Gallwey score. Another interesting thing they note is that “Growth of a cosmetically acceptable beard was not predictable; genetic variability among individuals may be responsible for that variation.”. This is interesting and highlights what you might also expect: there is, of course, some variation from one woman to the other. An equal dosage of an androgen might lead to different results in the extent of hair growth, or the pattern in which it grows, between individuals.

Treatment (or solutions, I should say)

Stating the obvious: hairs can be shaved, plucked or waxed, and in many cases this might already be good enough. However, not everyone likes these solutions for various reasons. Shaving needs to be repeated quite regularly and leaves hairs with a blunt point at the tip which might feel uncomfortable. It can also cause irritation to skin, and this is much the same for plucking and waxing of course—albeit to a larger degree. These latter two might even cause scarring, folliculitis or hyperpigmentation on occasion. Moreover, not all areas can be reached by yourself. Good luck waxing your own back.

Pharmacologically speaking, several treatment options are available, but they aren’t the brightest of choices if you’re using anabolic steroids. For example, oral contraceptives are being used. Their effect under physiological circumstances might be twofold: on the one hand they might decrease endogenous testosterone production (which is obsolete when exogenously administering anabolic steroids) and on the other hand they might increase SHBG, which leaves a smaller free fraction of testosterone/anabolic steroids circulating in the blood. In similar vein, antiandrogens are also sometimes prescribed to treat hirsutism. These obviously would also counteract the sought-after anabolic effects. This leaves Finasteride, which I touched upon earlier in this article. It counteracts the conversion of testosterone into the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). It does so by inhibiting the enzyme responsible for this, namely 5α-reductase (Finasteride is a 5α-reductase inhibitor). Dosages used for this purpose are in the 2.5 to 5.0 mg daily range. It should be highlighted that, if this were to work for exogenously administered anabolic steroids, it would only work for testosterone, as its virtually the only common anabolic steroids which is converted into a more potent androgen by 5α-reductase. See the table below.

| Compound | Can be 5α-reduced in the body? |

| Testosterone | Yes, to a more potent androgen (DHT) |

| Nandrolone | Yes, to a less potent androgen (DHN) [13] |

| Boldenone | No, not significantly 5α-reduced in the body [14, 15] |

| Trenbolone | No, not significantly 5α-reduced in the body [14] |

| Methandienone | No, not significantly 5α-reduced in the body [14] |

| Turinabol | No, not significantly 5α-reduced in the body [14] |

| Fluoxymesterone | No, not significantly 5α-reduced in the body [14] |

| Methenolone | No, already 5α-reduced |

| Drostanolone | No, already 5α-reduced |

| Stanozolol | No, already 5α-reduced |

| Oxandrolone | No, already 5α-reduced |

| Oxymetholone | No, already 5α-reduced |

Other options are hair removal methods such as electrolysis and photoepilation. Electrolysis is available as so-called galvanic electrolysis,, thermolysis, or “the blend method” which simply is a combination of electrolysis and thermolysis. This method is pretty damn time-consuming, as a needle needs to be inserted into every single hair follicle that you’d like to get treated. With galvanic electrolysis a direct current is passed through the needle to ‘electrocute’ the follicle, whereas with thermolysis an alternating current is used to, well, ‘fry’ it. The results are good and other than it being time-consuming, it’s tolerated well.

Photoepilation is a blessing if you don’t want lengthy treatment sessions. This makes it more feasible if large areas need to be treated. Basically it uses light at a certain wavelength to ‘laser’ the hair follicles. The light is absorbed by the melanin pigment of the hair strands and given off as heat to the surrounding follicle which damages it. This, ultimately, prevents the hair follicle from producing a new strand of hair. However, this method isn’t suitable for all types of hairs—as it relies on the melanin pigment of the hair strands. Thus it works less good for white and blond hair. Finally, photoepilation, for some reason, causes increased hair growth in the treated areas in some cases (around 10 % in one trial) [16].

Conclusion

Exposure to anabolic steroids can make women grow excess hair, a condition known as hirsutism. This hair will grow in the ‘manly’ places, like above the upper lip, the chin, the chest, upper arms, back, etc. Not all women are affected equally, so one woman might experience to a greater or smaller degree than another, and there’s also variation in the affected areas. Hirsutism usually takes quite some time to take place; several months of increased androgen exposure. So you won’t wake up with a moustache after a few days of anabolic steroid use. Anyhow, this side effect is purely cosmetic, can be easily monitored, and if desired can be dealt with with some of the options outlined above. As a final note: it’s most likely reversible, as it’s also reversible in conditions in which it’s the result of increased androgen exposure over time. When the increased androgen exposure is corrected, the hirsutism subsides.

References

- Yildiz, Bulent O., et al. “Visually scoring hirsutism.” Human reproduction update 16.1 (2010): 51-64.

- Escobar-Morreale, H. F., et al. “Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hirsutism: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society.” Human reproduction update 18.2 (2012): 146-170.

- Yilmaz, Bulent, and Bulent Okan Yildiz. “Endocrinology of hirsutism: from androgens to androgen excess disorders.” Hyperandrogenism in Women 53 (2019): 108-119.

- Ciotta, Lilliana, et al. “Clinical and endocrine effects of finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor, in women with idiopathic hirsutism.” Fertility and sterility 64.2 (1995): 299-306.

- Venturoli, S., et al. “A prospective randomized trial comparing low dose flutamide, finasteride, ketoconazole, and cyproterone acetate-estrogen regimens in the treatment of hirsutism.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 84.4 (1999): 1304-1310.

- Falsetti, L., et al. “Treatment of hirsutism by finasteride and flutamide in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.” Gynecological Endocrinology 11.4 (1997): 251-257.

- Lumachi, Franco, and Riccardo Rondinone. “Use of cyproterone acetate, finasteride, and spironolactone to treat idiopathic hirsutism.” Fertility and sterility 79.4 (2003): 942-946.

- Bergink, E. W., et al. “Comparison of the receptor binding properties of nandrolone and testosterone under in vitro and in vivo conditions.” Journal of steroid biochemistry 22.6 (1985): 831-836.

- Sherwin, Barbara B. “Randomized clinical trials of combined estrogen-androgen preparations: effects on sexual functioning.” Fertility and Sterility 77 (2002): 49-54.

- Huang, Grace, et al. “Testosterone dose-response relationships in hysterectomized women with and without oophorectomy: effects on sexual function, body composition, muscle performance and physical function in a randomized trial.” Menopause (New York, NY) 21.6 (2014): 612.

- Braunstein, Glenn D. “Safety of testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women.” Fertility and sterility 88.1 (2007): 1-17.

- Meyer, Walter J., et al. “Physical and hormonal evaluation of transsexual patients: a longitudinal study.” Archives of sexual behavior 15.2 (1986): 121-138.

- Bergink, E. W., et al. “Comparison of the receptor binding properties of nandrolone and testosterone under in vitro and in vivo conditions.” Journal of steroid biochemistry 22.6 (1985): 831-836.

- Schänzer, Wilhelm. “Metabolism of anabolic androgenic steroids.” Clinical chemistry 42.7 (1996): 1001-1020.

- Schänzer, W., and M. Donike. “Metabolism of boldenone in man: gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric identification of urinary excreted metabolites and determination of excretion rates.” Biological mass spectrometry 21.1 (1992): 3-16.

- Willey, Andrea, et al. “Hair stimulation following laser and intense pulsed light photo‐epilation: Review of 543 cases and ways to manage it.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine: The Official Journal of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery 39.4 (2007): 297-301.

About the author

Peter Bond is a scientific author with publications on anabolic steroids, the regulation of an important molecular pathway of muscle growth (mTORC1), and the dietary supplement phosphatidic acid. He is the author of several books in Dutch and English, including Book on Steroids and Bond's Dietary Supplements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.