Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Introduction

This article is not just about female bodybuilders or fitness competitors. It is not about who is posing where and how. It is not about who is more feminine, athletic, sexy, muscular, or appropriate. It is about the creation, maintenance, and representation of a so-called crisis.

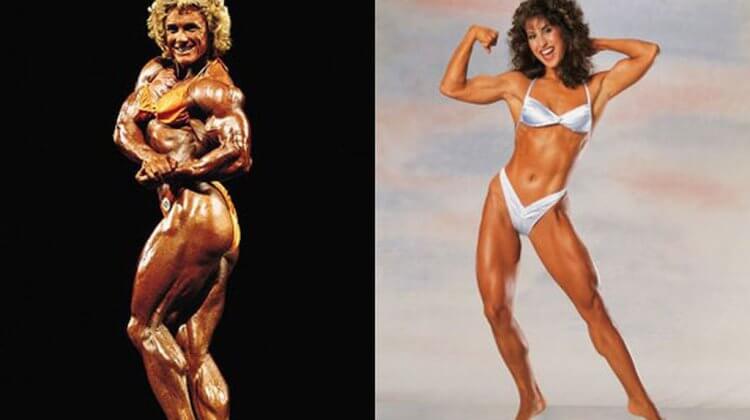

Avid watchers of physical culture, or anyone who reads mainstream muscle mags on the Stairmaster, will know that in recent years a “crisis” has been introduced into the world of women’s bodybuilding. This crisis is, of course, the appearance of fitness competitors, who are lauded by supporters as providing an athletic yet feminine alternative to ungainly and androgynous female bodybuilders, and criticized by detractors as being little more than pectorally amplified lingerie racks.

This apparent schism found its way finally to the New York Times in an article entitled, “Female Bodybuilders Discover Curves“. The author writes, in part:

“When the history of women’s bodybuilding is written, 1998 will emerge as the year that the weights tipped in favour of the sport’s old nemesis, femininity…. Fitness competition, a slenderized version of women’s bodybuilding, has eclipsed some of the bulked-up muscle shows in participant and audience popularity.”1

Female bodybuilders, so the story goes, are lumpy and icky and threatening to their gender. They used to be nice and acceptable in the days of Rachel McLish, then things got out of hand. Fitness competitors, according to the New York Times article, are providing viewers and participants with a more socially acceptable kind of female athletic ideal, since they pose in heels and evening gowns. They do lingerie and swimsuit pictorials in muscle mags which, according to Leslie Heywood, verge on pornographic. Female bodybuilders, strength trainers, and powerlifters are said to ridicule this new ideal as “bodybuilding lite”. Even feminists are in on the act, according to the New York Times article.

What this amounts to is media salivation over a perceived spectacle of a catfight par excellence (though feminists can generally be counted on in mainstream media depictions to rain on everyone’s parades). Interestingly, though fitness competitions for men are apparently also on the rise, and are, according to the Times, “expected to attract more participants than traditional bodybuilding competitions”, little is heard from muscle mags about the crisis in men’s bodybuilding. Male bodybuilders are not “discovering leanness” or being haunted by their “old nemesis of masculinity” (such a possibility in fact seems patently ridiculous). I begin to suspect that this crisis is greater than a schism over the Bodybuilding Reformation. Rather than rooting for one side or the other (since after all, wouldn’t those fitness competitors just hog all the good cheerleaders?), or providing learned explanations on why female bodybuilders are really just nice girls, or why fitness competitors are really in good shape, it is more interesting to consider the meaning of the crisis itself. What is actually behind the promotion of a crisis anyway? Why is it necessary to juxtapose the success of fitness competitions with the perceived failure of bodybuilding competitions? Why is the so-called crisis cast in terms of discovering/rejecting femininity?

Crisis and its Discontents

Speaking in another context which I think is applicable here, Geraldine Heng and Janadas Devan write:

“It is a… truism that they who successfully define and superintend a crisis, furnishing its lexicon and discursive parameters, successfully confirm themselves the owners of power… [T]he habit of generating narratives of crisis at intervals becomes an entrenched, dependable practice… when a distortion in the replication or scale of a composition deemed ideal is fearfully imagined.”2

In other words, the generation of a crisis is a reliable institutional response to a perceived threat to the status quo. Political cynics argued that Clinton bombed Iraq to divert attention from his infidelity and perjury troubles. The post-WWII governmental propaganda machine dispensed countless instructional films on why mothers who continued to work in the factories could count on their children becoming serial killers. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century scientists lamented the degeneration of “the race” in the face of geographical migration by countless thousands of people. And so forth. One need not be overly paranoid to note that the best defense is a good offense.

Female participation in athletic activities has always had a dubious foundation. It’s an odd coincidence that just as more girls than ever—perhaps inspired by Gabrielle Reece, Flo-Jo, the women’s Olympic hockey teams, Nike, or Title IX—are taking up sports, a crisis arrives in how to represent them (or how they choose to represent themselves). In fact, this crisis seems designed to get them fighting amongst themselves. Female powerlifters sneer at bodybuilders, who sneer at fitness competitors. Average female recreational athletes sneer at all of them for being obsessed with perfection in their particular subcultures. Each group feels compelled to defend their tiny piece of turf that they have managed to swipe and subdivide from the larger sports-entertainment complex. And meanwhile the mainstream media gleefully runs stories of steroid deaths, ephedrine overdoses, muscle dysmorphia, aerobics obsessions, musings on just what is wrong with Calista Flockhart to be so skinny and Kate Winslet to be so “full-figured”, why diets don’t work but obesity kills, etc. etc.

In isolation, these things make sense (why wouldn’t female bodybuilders be jealous of fitness competitors? everyone wants femininity!). But together, and cumulatively in their omnipresence and repetition, these elements provide a disturbing synthesis. What agenda is served by promoting a crisis? What ideologies lie behind the contradictory messages that women and girls receive about sport, fitness, exercise, and its representations? What is achieved by setting up women athletes against one another?

I’ll Scratch Her Eyes Out

Generating internal conflict amongst women is nothing new. From the earliest days of the “virgin-whore” dichotomy, encouraging women’s hostilities to one another has been a familiar divide-and-conquer tactic, whether it was maternal feminists against militant suffragettes, “career women” against “stay-at-home-moms”, or wives against “the other woman”. Advertisers have known for years that cosmetics are like sports supplements for women seeking an advantage on the perceived competition. In situations with limited actual power, it’s not hard to incite dissent amongst the ranks and turn hostility inward instead of outward, to prevent any kind of critical structural analysis.

There are a variety of ideologies behind promoting a crisis in women’s athletic representation. In general, manufacturing a crisis ensures that women are prevented from working with one another to secure some actual power. If they spend their energies turning up their noses at one another they will not be knocking on institutional doors en masse, demanding more money for female sports. They won’t be supporting one another. They won’t be working together across their differences to make things better for other women. Instead, they’ll be fixated on fighting over that most intangible of qualities, “femininity”. Furthermore, success is often defined in competitive posing circles as who can score the most lucrative supplement contracts. The mass media is a testing ground to see which strategy is most successful in moving products off the shelves of the local GNC. There’s nothing quite like a good scrap to get people’s attention, and female consumers can be reassured that the products they purchase will not make them “unfeminine”.

Whose femininity is more feminine is a grizzled cliche in women’s bodybuilding circles by now. I find the application of “femininity” as a criteria for success in a sport an interesting one, and perhaps on one level it speaks to the uneasy relationship that bodybuilding competitions have with beauty pageants. To explore the idea of pageantry alone is poignant enough: the Miss America pageant appeared the year that women got the vote in the early 20th century, and women’s bodybuilding competitions emerged at a time of great political and social gains for women (short years after women threw corsets and bras into a trash can at a beauty pageant, an event which gave rise to the myth of “bra-burning”). On another level, what relevance does the question of femininity have to an activity that judges the degree of muscular development on a body? I think the answer lies in another question: what kinds of cultural anxieties are being expressed in discussions of female bodybuilders’ femininity?

Throughout history there have been few enduring icons for the projection of cultural and social fears that have had the power of the female body. Implicit in the “discovery of curves” by female bodybuilders is a call to return to a happier time when boundaries between genders were narrowly defined and rigidly enforced, where there was little diversity or change encouraged and everyone liked it that way. The false nostalgia for femininity (for, in truth, there has never been a time when everyone of either gender happily and mutely settled into their assigned roles) reflects more about the present than it does about the past. Susan Faludi writes, “The demand that women ‘return to femininity’ is a demand that the cultural gears shift into reverse…”3 Does the so-called crisis in female bodybuilding represent an attempt to divide and conquer with regard to women’s engagement in fitness and weight training?

Interestingly, the New York Times article on female bodybuilders and fitness competitors is next to a short piece entitled, “Babies on Sideline as Moms Work Out.” The article text is about a “Strollercize” exercise class in which an instructor bellows at new moms: “‘Why do we lunge, everybody?… Because we need the strength to pick up those toys!’” And even in this idyllic picture of moms and babies we hear a hint of “the other woman”. One new mom says: “It’s tough to stroll down Madison [Avenue] with all the size 2′s, so it’s nice to be with other mothers who are going through the same thing… I wouldn’t be caught dead in a gym right now.”4 Mere inches away from this text I read that the current Ms. Fitness, Susie Curry, is 5’2″ and 115 pounds, perhaps the stereotypical “size-2″ that the new mom wishes to avoid. Does this new “fitness ideal” promoted by the mass media really represent a return to femininity or a new way to generate insecurity and a false sense of crisis? Do women see themselves emulating either the female bodybuilder or the fitness competitor or are both mocking icons of ideal and unattainable bodies? The female bodybuilder, we are told, is a masculine steroid freak whose practices of gaining muscle and reducing fat are “unhealthy” (I read “unhealthy” as another word heavily laden with unspoken meanings), yet the female fitness competitor sports high heels and breast implants, low bodyfat, and the ability to engage in grueling aerobics routines with a smile on her face. Is the so-called crisis in female bodybuilding really about competition for the attention of the female consumer?

Boundary Politics

As I flip through the sports section in Canada’s national paper The Globe and Mail, I am entranced by a photo of Mary Pierce having just smashed a tennis ball into the next dimension. Her tanned arms and shoulders are big and muscular as they peek out from her Nike tennis dress. The copy in the accompanying article says in praise of another female tennis player, “The right-hander from Laye is a strong 5-foot-10 and 145 pounds and is able to exploit her size on her serve and ground strokes.” Here is an arena where female size and power are rewarded. There is a second photo with the article, this one of six Mary Pierce fans, male and female, who are all attired in blond wigs and Pierce’s trademark gold tennis dress. It’s an interesting gender-bending homage.5

Faludi writes in Backlash that the prevailing wisdom about women’s apparent collective “unhappiness” (or the crisis in women’s bodybuilding, as the case may be) is that “[w]omen are enslaved by their own liberation.”6 Implicit in the coverage of the so-called crisis is the sense that female bodybuilders have brought their own doom upon themselves. The appearance of Bev Francis’ incredibly powerful physique in the early 1980s is sometimes held up as the beginning of the end. Women bodybuilders got ahead of themselves, so the hand-wringing copy goes. They were out of control. They got too big, too freaky, too drugged-out, too lean, too scary. They were the dragon from which the damsel-in-distress-femininity had to be saved by the fitness competitors. Female bodybuilders and fitness competitors were thus cast as enemies in the morality play of women’s fitness representations.

To paraphrase Faludi, to blame female bodybuilders for the destruction of femininity is to miss the point of female bodybuilding, which was to open up a new set of experiences for women as strong, physically powerful beings. Weight training for women is extremely beneficial, and no scientific evidence supports the notion that women have to train differently from men lest they risk “getting too big” or otherwise damaging themselves. The fact that fitness competitors are being set up against female bodybuilders should tell us that negotiation of gender boundaries is still a hot topic which is profoundly reflective of our own cultural and social anxieties. There is no surer way to shore up borders than to prepare for a state of war. There is no surer way to reinforce traditional gender divisions than to present physical diversity as a threat. It’s not about which is better; it’s about what “better” means, and what agenda defines it.

Notes

Marlene Roach, “Female Bodybuilders Discover Curves“, New York Times (Nov. 10, 1998), D9.

Geraldine Heng and Janadas Devan, “State Fatherhood: The Politics of Nationalism, Sexuality, and Race in Singapore”. Nationalisms and Sexualities (ed. Andrew Parker et al). (London: Routledge), 343-4.

Susan Faludi, Backlash (New York: Doubleday, 1991),70.

Kimberly Stevens, “Babies on Sideline as Mothers Work Out”, New York Times (Nov. 10, 1998), D9.

Tom Tebbut, “Women Playing Up to Form”, Globe and Mail (Jan. 24, 1999), S1.

Faludi, x.

About the author

Krista Scott-Dixon, PhD, earned her doctorate in Women’s Studies from York University. She holds counseling certifications from George Brown College and Leading Edge Training, which is certified by the Canadian Psychological Association. Currently, she’s pursuing a master’s degree in Counseling Psychology at Yorkville University in New Brunswick, Canada.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.