I have been an athlete all my life, having participated in everything from basketball to figure skating, but focused on volleyball and rugby as a York U Varsity athlete. Sport wasn’t just something I did, it represented who I was and, more importantly, what I wanted to become. I first started training with weights after university at a fitness club in Toronto. Initially, I was interested in training for triathlons, but soon found I enjoyed strength training more than I had expected and results came quickly with relative ease. Given my history of athletic participation, educational background in Kinesiology, academic interest in feminism and personal views regarding sexuality, bodybuilding for me represented a point in my life where all of these elements collided into one big grand experiment. I was drawn to the feeling of physical empowerment the weights provided that I never received with aerobic conditioning. Bodybuilding seemed to be a natural progression and an ideal fit after years of participating in team sport. It provided me with the opportunity to pursue an individual sport where I would be completely responsible for my own success and/or failure.

At first, the sport was an alien subculture to me, as it is to many others and even more so with women. While some individuals quest for the perfect body to be admired by others, my goal was to develop a competitive physique that would be one day be worthy of a championship title. It was always about athletic competition for me and unfortunately, not everyone saw my goals as compatible with their own and the attention I received proved difficult to get accustomed to. Reactions have always been both positive and negative right from the start as, unlike female athletes in other sports, women who compete in bodybuilding are immediately recognizable and always on public display. I grew tired of talking about my best lifts, the size of my arms or what the best exercise was for complete calf development. People were forever commenting on my physique, motives and ability to be successful in the sport, reflecting their own perceptions primarily influenced by negative media attention and false information having little to do with my own experience.

Although I was a straight female athlete throughout my years in sport, issues surrounding heterosexism have profoundly affected me, which have had a tremendous influence on my life. It wasn’t until a few years ago that I realized that this identity was no longer compatible with the person I knew I was becoming. I certainly wasn’t as straight as I thought (and probably hoped) I was. Bodybuilding has played a role in how I view my sexuality and raised my awareness of the power it has over others. It is one thing to understand how we are constructed in terms of gender, but quite another to have lived through the experience. All of a sudden, I was made to feel that I must be a man stuck in a woman’s body or that I wanted to morph into one. But that was not the case for me at all, I have never felt like a man, nor was I interested in becoming one. I don’t equate my value as an athlete with my level of sexual attractiveness, so whether or not someone found me more or less attractive because of my physique was not my concern. It had nothing to do with wanting what men have; it was about having the freedom to decide which physique I wanted and the opportunity to be able to do it. I still find myself defending this position to the present day.

As a human being, sexuality is important to me, but as a female bodybuilder it was the furthest thing from my mind. I’ve always believed that it is not our sexuality that defines us as athletes, but our passion for sport that allows us to share a set of common experiences unique to those who choose to compete. However, I have spent a great deal of time defending my sexuality, athleticism and right to be an equal participant in the sporting world. I have been warned against playing for particular Universities based on the coach’s reputation; failed to report sexual assaults on campus out of fear of being labeled a dyke; discouraged from participating on teams known to be filled with those types of girls; prevented from bonding with teammates and coaches fearing guilt by association; endured attacks from other players for associating with known lesbians; ended friendships with women stigmatized by the lesbian label; silenced and denied (apologetically-so) leaving me with deep feelings of loss and regret. It is for these reasons why it’s important to me to be open about my experiences in sport, because there’s too much at stake for those that still don’t get it.

Perception of Reality

There are a number of misconceptions in the sport of bodybuilding and regarding its participants from my perspective.

Anyone can be a successful competitive bodybuilder.

As in any professional sport, the athletes that rise to the top have been genetically advantaged to excel in that particular contest. In bodybuilding, you either have it or you don’t and while great genetics doesn’t guarantee you a successful career, it does determine what the final product looks like. In the end, it is the individuals that do the most with what they’ve got that usually come out on top.

Female bodybuilders are trying to turn themselves into men.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. If anything, women that transform their physiques are attempting to become better women, not men. I attribute this thinking to a society that continues to be disturbed by their level of physical development due to commonly held misconceptions of gender and being unable (or unwilling) to separate an athletic pursuit from a woman’s sexuality. Some will always see female athletes in sexual terms and use them explain what they don’t understand. If a woman with muscle is more of a man, is a man without muscle more of a woman?

The majority of female bodybuilders must be lesbians or they wouldn’t want to look the way they do.

I don’t know if there are any more or less lesbians in female bodybuilding than there are in any other sport or in society in general. I do know that most women who build competitive physiques are doing so for themselves, some even do it for the men they are already involved with; husbands, boyfriends, coaches and trainers. Some think that if women aren’t focused on appealing sexually to men that she must be attracted to women, but not every pursuit is motivated by sex. The bottom line for many rests on athleticism, competition and personal achievement, not about scoring more numbers to beef up a little black book.

Female bodybuilders use drugs to build their physiques, while the men rely on supplements.

It seems obvious that the major changes began happening to the women’s side of the sport as the nature of the supplement industry changed. Female bodybuilders suddenly became less marketable to female consumers targeted for products that promised a magic pill to lose weight, burn fat and gain muscle, but only a little bit. They have created a situation where consumers with little knowledge about the issue are made to believe that men use supplements to develop their physiques, while the women, who are not supported by these same companies, use drugs to develop theirs. Supplement companies promote their products as natural alternatives to drugs, while using enhanced athletes as walking advertisements. These companies benefit from the association consumers make with the level of development the athletes exhibit and their products even though one may have very little to do with the other.

Female bodybuilders are to blame for sport’s lack of mainstream appeal.

The industry continues to contribute to the notion that the women get what they deserve and are to blame for the sport’s lack of mainstream appeal. If drug use among the competitors is, in fact, a major obstacle preventing mainstream acceptance, then the answer is simple; drug test the athletes. They can’t have it both ways. Either enforce mandatory drug testing across the board and deal with the results on an individual basis or don’t test the athletes and stop assigning blame only to the women as a group, judging them all by the worst, rather than the best available examples in the sport. Many female bodybuilders are highly educated professionals, who rarely get credit for the contributions them make to the sport and society in general usually taking a back seat to swimsuit spreads and profiles with bikini models.

Women are just not biologically suited for muscular development.

Females are taught to halt the development of their bodies because of this cultural proscription against women being strong, receiving messages to not get too big or muscular so as to appear non-threatening. What may prevent women from taking advantage of their natural physiology is not their bodies, it is that these biological tests have turned into a social rules that encourage them to remain inactive and weak. We won’t know what women are truly capable of until they stop putting their bodies through a constant disciplining regime of some sort whether is be in terms of caloric restriction and/or excessive exercise with the end goal being to tear down rather than build up their physiques. Given the same opportunities, the gap between male and female athletes is much narrower than they would like to believe, dependent upon social forces rather than biological determinants.

The Straight Goods

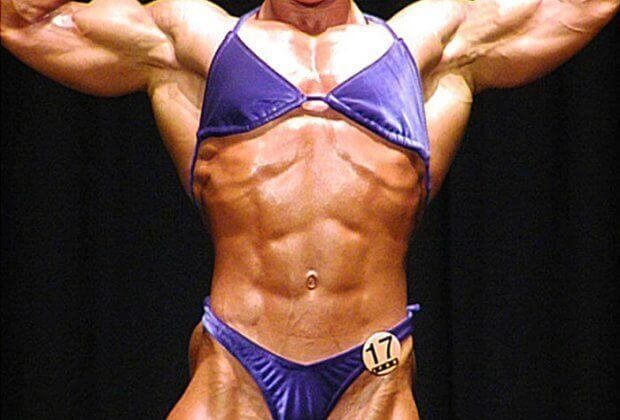

Bodybuilding competitions are based on the aesthetics of an athlete’s physique in comparison to other individuals judged on symmetry, muscular development, conditioning and overall presentation. Competitors are judged based not only on how they look when standing alone, but how they look in comparison to the other athletes on stage that day and at that particular time. The sport is not only focused on physical development, but about targeting a specific demographic using extreme versions of masculinity and femininity represented to an audience believed to prefer to see sex (of a particular kind) at shows. For women in particular, it is not a sport about performance, but about who fits the criteria of acceptable womanhood that varies upon different individuals at the same show. For those athletes that compete for points based upon how they look, rather than against an opponent or clock, the situation becomes far more complicated. Final judgments are left up to the discretion of individuals that score a woman’s physique based on guidelines that have less to do with muscular development and more to do with personal preference.

Many women in the sport will define themselves publicly as muscular, yet feminine, having retained something that the others have apparently lost sometime ago. They attempt to separate themselves from the rest of the pack mistaken in their belief that they will be seen as the exception, rather than the rule. Most take great pains to establish their femininity and go overboard in proclaiming their heterosexuality in a number of subtle and not-so-subtle ways. To clarify some of the bodybuilding jargon as it relates to its female participants, mainstream means appealing to a young heterosexual male demographic who require that any and all female athletes look like strippers in order to justify buying protein powder from the women that sell their photos/selves at booths set up by supplement companies. Healthy means voluptuous, new look means silicone and endorsement contracts mean free T-shirts and such. Increased prize money is the proverbial carrot that gets hung out in front of the female competitors in an attempt to convince them that those that comply will find a pot of gold at the end of the industry’s rainbow.

The current state of affairs for the women in bodybuilding is not a positive one and continues to reinforce the same sexist stereotypes that has created an increasingly negative atmosphere, where female bodybuilders have been hung out to dry in terms of sponsorship and other financial opportunities off stage. Although more money is being made than ever before within the industry, the women are competing for less now than they were 15 years ago, while the men’s prize money has continued to increase with each passing season. The women have become victims of their own success and constantly subject to changing guidelines thought to increase their marketability and sponsorship opportunities, even though they have been completely removed from every magazine, marketing piece and promotional item. The men compete as respected professionals and are rewarded accordingly, while the women are expected to be grateful that they’ve even been allowed to participate. Marketability has replaced physical ability where the bottom line now serves as the dividing line between the have’s (men) and the have nots (women). As a result, the women have learned to justify and/or apologize for their physiques in order to be accepted by a population that fails to understand it.

Rules of the Game

Athletics has given me the opportunity to challenge conventional notions of what it means to be a woman although, like most female athletes, I have spent a great deal of time conforming to, defending against and asserting myself to a society where female athletes must exhibit a level of sexual attractiveness that appeals to an artificial standard of femininity. I knew from the beginning that I wasn’t going to fit in very well; being coy is not one of my stronger attributes; neither is doing gender or playing the femininity game. I found that most female bodybuilders represent a contradiction in terms. On the one hand, their image portrays a rejection of the ideal female form and, on the other, an attempt to make up for it by adhering to traditional expectations. Female bodybuilders have acknowledged society’s view of the feminine ideal and have chose to reject it on some level, yet many still allow themselves to be judged by it.

Athletes are categorized by gender rather than athletic ability in order to ensure that they remain in opposition to one another, which suppresses evidence of variance among individual characteristics required for success in competition. Elite athletes look and act more alike than they do different, exhibiting traits that are common to them as a group and not assigned to one gender over another. Women that willingly play the femininity game set a standard for female athletes to be judged by their success as feminine women, rather than their value as competitors in their own right. Although this game is one that everyone is expected to participate in voluntarily, the winners have usually been predetermined ahead of time. Female bodybuilders have the distinct ability of allowing others to question if muscle really does have a gender. How is femininity defined in a sport that requires that female competitors be unfeminine by traditional standards in order to pursue it? Is it standard for all women or does it vary in degrees from one athlete to another? If it exists along a continuum, at which point is the line drawn between un/acceptable levels and how much variation is acceptable? Who makes the final call should there be discrepancy among judges?

Identifying femininity as a deciding factor in the overall assessment of female bodybuilders, which requires they adhere to standard notions of what a woman should look like is clearly discriminatory towards female athletes as there are no such similar attempts made to enforce masculinity on the men’s side. The fact is that femininity cannot be defined, regulated or judged as unacceptable by any representatives claiming they are in a position to do so. What these terms really attempt to regulate are notions of gender compliance that project a public image that IFBB professional athletes are ‘real’ men and women, not to be feared by mainstream interests.

Body Wars

Female muscularity is thought to be particularly offensive to a number of mainstream publications as it contradicts notions of gender appropriateness. Muscular women and mainstream models both represent extreme levels of physical development, sharing a similar goal to drastically alter their body composition, but representing polar opposites in terms of acceptability and perception by society. One is celebrated by the media, while the other is criticized; one is highly marketed and the other rarely publicized; one is set up for mainstream acceptance and the other for certain rejection. We as a society turn a blind eye to the negative impact of the fashion model while simultaneously refusing to acknowledge the potentially empowering message of a strong female physique.

Female bodybuilders continue to be compared against images that all females must aspire to and few will ever achieve, although most inevitably spend a lifetime trying. How much money, and subsequent power, would be lost if women refused to be locked into a single body ideal, but rather presented themselves as they really are? Would the images differ and would they reinforce existing myths about women’s bodies or would they construct new, more realistic versions of the diversity of the female physique? What if female athletes stopped competing for male approval and changed their target audience to women exclusively…would their attitudes and behaviours change? Would they continue to promote a highly sexualized image for other women that may or may not be interested in their attractiveness, but instead on their athletic accomplishments? How many years must women participate in sport before their involvement is viewed as compatible with their assigned gender? If you think muscle on a woman is offensive, try looking at one without any.

Sexuality plays an important role in the construction of gender and power relations in sport and as women have become physically stronger, homophobia has gotten increasingly more powerful to keep up with the demand. Homophobia for women is not a fear of lesbians; it is the fear of being called one. It stands to reason that judging a female athlete based on her beauty is like judging a supermodel based on her hook shot. If sexuality didn’t matter, then sexualization wouldn’t be necessary, as it is much easier to accept a muscular woman if she is portrayed as a sexual object for public consumption. However, when competitors are routinely portrayed in a way that prevents them from being taken seriously as athletes, then bodybuilding for women never stands to gain the respect it deserves or the payoffs it’s capable of. When any female athlete is identified more often with lingerie than with workout wear, it’s difficult to find a way to promote her as a serious contender when show time comes around.

I doubt that going mainstream should include the opportunity to be equally exploited alongside other women or that liberation means that we should all be able to pose for magazines that get wrapped in plastic, so women everywhere know that it contains nothing in it for them. “Men are interested in seeing strong women who aren’t afraid to be sexual” goes the argument, but their motivation is likely just the opposite. They may be more afraid not to be sexual in an industry that demands their full cooperation when it comes to the focus on breasts over biceps. It simply becomes impossible for women to be equally competitive in sports that include female athletes as centerfolds, spread-eagled and airbrushed, in the middle of every player’s official rulebook.

Image and Damage Control

We have been divided along lines of gender and sexuality, rather than athletic ability and forced to compete with one another for things that have nothing to do with performance on stage.

There is a very specific audience for bodybuilding as a sport, but there is a much larger audience for women’s physical development in general. Competitive bodybuilding is very structured and requires a great deal of discipline, but for the majority of women that train with weights, it allows them to have options beyond that of the ideal female form currently portrayed in mainstream advertisements. If the industry would spend more time showcasing the participants as athletes, rather than amazons, then the public would be able to gain a better understanding of the sport itself.

As female athletes, we battle issues surrounding body image, sexuality and sexual orientation; being too big, too muscular and not feminine enough. I’ve always been more concerned about the freedom for women to develop their physiques as they see fit, rather than ascribing to traditional notions about what a woman’s body should look like. In the struggle for women to gain control over their bodies, bodybuilding can serve as a way to empower women physically and inspire other women to build up, rather than break down and to become strong, rather than remaining weak. The existence of muscular women alone allows others to train with weights and develop stronger, more powerful physiques, because they had the courage to go there first.

Whether sexuality is a choice or something you’re born with, the time I have spent as a bodybuilder has led me to the conclusion that those who attempt to conform to someone else’s version of reality will inevitably live a life filled with frustration. I don’t know which side of the nature/nurture debate I fall upon, although I tend to believe that there is a combination of factors that go into all aspects of personal and individual development. As women, we are only able to compete in sport because of the battles fought long ago by a number of athletes who sacrificed their images, reputations and lifestyles, risking tremendous public scrutiny in the hope that those who followed would have an easier road to victory. I am both a woman and an athlete, but realize that women compete in a number of sports that see these as mutually exclusive and choose the former to gauge a successful performance. Hopefully, more women will begin to see their beauty lies more in their strength than in their weakness and stop playing games that don’t matter in order to focus on the ones that do.

About the author

1999 CBBF Canadian National Bodybuilding Championships - 1st Heavyweight

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.