In this article we’ll go over some of the (purported) treatments for gynecomastia in anabolic steroid users. As we’ve established in the previous article, the culprit of gynecomastia development in anabolic steroid users is an imbalance between androgenic and estrogenic action on breast tissue. If it develops during a cycle, it’s likely due to an absolute estrogen excess as a result of aromatization. After a cycle, when a transient period of testosterone deficiency commences, there’s an absolute deficit of androgens in the body with the possibility of a relative excess of estrogens. As such, it’s no surprise that endocrine therapy of gynecomastia revolves around decreasing estrogenic action.

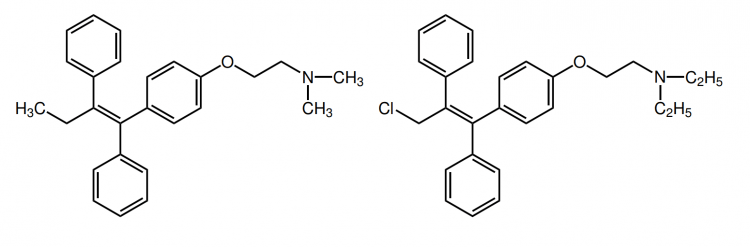

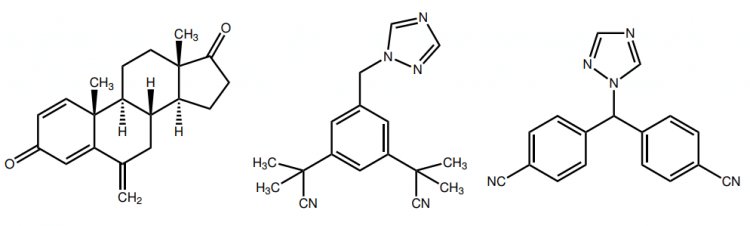

Two classes of drugs are commonly used for the purpose of treating gynecomastia. One targets the estrogen receptor, by function as an antagonist in breast tissue. This class of drugs is known as selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). Some examples belonging to this class of drugs are clomiphene (Clomid), tamoxifen (Nolvadex) and raloxifene (Evista). The other class of drugs targets the aromatase enzyme and thereby decreases the conversion of androgens into estrogens. These are known as aromatase inhibitors (AIs) and some examples are exemestane (Aromasin), anastrozole (Arimidex) and letrozole (Femara).

Let’s have a look at what the scientific literature has to say about the efficacy of these different treatment modalities. At the end of this article I will also briefly discuss some forms of surgery. As, after all, endocrine treatment, unfortunately, doesn’t always lead to full satisfaction. This unresponsiveness might, at least in some cases, have to do with how the glandular tissue develops over time. As it turns out, gynecomastia undergoes (irreversible) fibrosis and hyalinization over time [1]. The resulting tissue will be unresponsive to endocrine treatment. Some estimates have been made about the time required for this process to occur, with estimates varying from 1 [2] to 2 years [3]. However, regardless, successful treatment of gynecomastia present for more than 2 years with tamoxifen has been reported [4].

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs)

SERMs are drugs that work as a (partial) agonist for the estrogen receptors in some tissues, and as a (partial) antagonist in others. For example, it can have agonistic properties on the estrogen receptors in bone tissue, thereby adequately maintaining bone mineral density, while also having antagonistic properties in breast tissue. This means that it will block estrogens from binding to the estrogen receptors there, while not activating the receptor itself. As a consequence, the estrogenic action in this tissue is diminished. The mechanisms behind this are similar as those through which selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) are supposed to be working. Briefly, this involves a differential regulation of cofactor recruitment between tissues. And, in the case of SERMs, this also involves how these compounds differentially affect the estrogen receptor (ER) isoforms α and β and their relative concentration in the respective tissues. In general, the ERβ is seen as a negative regulator of the ERα [5].

But now I’m starting to drift off. Let’s focus on what’s important here, and that’s that SERMs are able to counteract estrogenic action in breast tissue. As a result, they have the potential to be a treatment option for gynecomastia.

Tamoxifen is one such SERM and is, arguably, the most popular one in the treatment of gynecomastia, albeit off-label. And, in my opinion, it’s rightfully the most popular one. A 2014 review paper published in the journal Nature Reviews Endocrinology notes that “Tamoxifen doses of 10–20mg daily used for 3–9 months have shown efficacy of up to 90% for the resolution of gynaecomastia.” [3]. Similarly, a slightly older review published in the New England Journal of Medicine writes that “(…) tamoxifen, administered orally at a dose of 20 mg daily for up to 3 months, has been shown to be effective in randomized and nonrandomized trials, resulting in partial regression of gynecomastia in approximately 80% of patients and complete regression in about 60%.” [6].

As noted earlier, there are worries that the longer gynecomastia has been present, the less responsive it will be to endocrine treatment. Something else that might affect it, that I haven’t touched on yet, is the size of the gynecomastia. With the larger it is, the lower the efficacy of endocrine treatment might be. There are two trials which I’d like to highlight in this regard. The first is a 10-year prospective cohort study of 81 idiopathic cases of gynecomastia [7]. They report a complete resolution of gynecomastia in response to tamoxifen in 90,1 % of their cases. Notably, what is reported as the “mean duration of swelling prior to treatment” (i.e. how long gynecomastia was already present before commencing treatment) was a few months longer (22 months) in those who achieved complete resolution compared to those who didn’t (17 months). This, of course, doesn’t preclude the possibility that the age of gynecomastia can’t affect treatment outcome. I’d say it does suggest that, if your gynecomastia is roughly 2 years old (or less), endocrine treatment is a viable approach. The authors also performed ultrasound to pretty accurately determine the size of the gynecomastia and it appeared that, the larger the size of the gynecomastia, the lower the chance of complete resolution by tamoxifen treatment. However, despite the difference being more than twofold in size between those who did and didn’t achieve complete resolution, this didn’t reach statistical significance. (The sample size was too small for those who didn’t achieve full resolution.) Finally, the high percentage of success in this trial might be attributed to the duration of treatment applied in this trial. The authors have let the duration of treatment depend on a response rather than using some rigid treatment protocol with a predefined amount of time. The mean duration in the group achieving full resolution was almost 7 months, with a standard deviation of almost 5 months. Patience is a virtue.

The second trial I’d like to highlight is a prospective cohort of 43 patients with gynecomastia due to various causes (most pubertal, but also caused by medication, secondary hypogonadism, toxic exposure and three with no known cause: idiopathic) [4]. Again, subjects were treated with tamoxifen (20 mg daily for 6 months) and the authors report that “Fifty two percent of gynecomastias over 4 cm and 90% of those of less than 4 cm in diameter disappeared (p<0.05).”. This is pretty much in line with the previous trial I highlighted, namely that size is a determinant of the efficacy of endocrine treatment with tamoxifen.

So what about the other two SERMs that I’ve mentioned? There’s actually very little about the two other options in the scientific literature. For clomiphene, trials generally show a poor (or moderate at best) response to treatment, with the most recent one I could find stemming from 1983 [8]. I guess because of the poor results researchers weren’t that interested in it anymore (especially given that tamoxifen was around too and actually did a good job). It’s hard to say why clomiphene doesn’t seem to work well. The most obvious reason might be that it’s simply not antagonistic enough in breast tissue. However, somewhat to my surprise, there don’t appear to be any studies which have evaluated the potency of clomiphene in breast tissue [9].

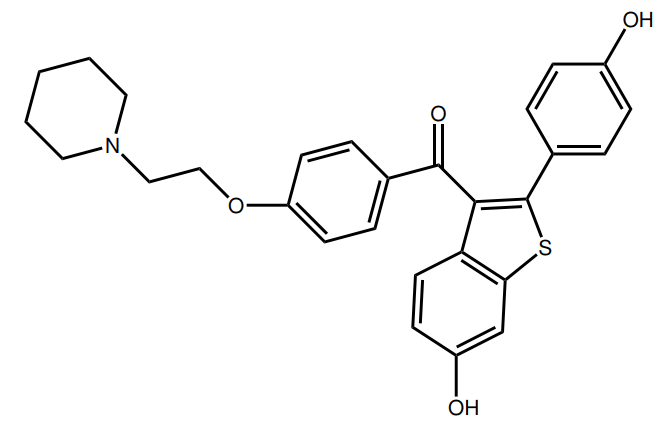

Finally, there’s raloxifene. While also a SERM, it belongs to a different chemical class of SERMs than tamoxifen and clomiphene. Tamoxifen and clomiphene belong to the triphenylethylene/chloroethylene derivatives, whereas raloxifene is a benzothiophene. Unfortunately, I’ve only been able to find one clinical trial of raloxifene in the literature in which it’s used as a treatment for gynecomastia [10]. The trial was a retrospective chart review, and not a randomized-controlled trial. As such, this leaves the results open to all sorts of biases and great caution should be taken when interpreting these results. Nevertheless, the results seem promising and I really wonder why no follow-up trials have been performed, given that this trial dates back to 2004. Anyhow, the patients in this trial received either tamoxifen (20-40 mg daily) or raloxifene (60 mg daily). When looking at the mean reduction in breast nodule diameter, it was slightly larger in those who received raloxifene (2.5 cm versus 2.1 cm). Both treatments scored similarly in the patient’s response to treatment. However, the authors note that, when solely looking at those showing a reduction greater than 50 %, those treated with raloxifene showed a greater response (86 %) than those treated with tamoxifen (41 %). Again, caution should be taken when interpreting these results. This doesn’t mean that raloxifene is better. One problem is the retrospective nature of the trial: subjects weren’t randomized to treatment. Another is that the subjects who received tamoxifen had a greater baseline breast nodule diameter (0.8 cm larger) although this wasn’t a statistically significant difference. Yet another is the small sample size; 7 with measurements of the nodule diameter in the raloxifene group, and 13 in the tamoxifen group. Finally, whereas the smallest reported breast diameter was 3 cm in the tamoxifen group, 3 of the 7 subjects of which there were measurements of the nodule diameter in the raloxifene group had a baseline breast diameter 1.5 cm (and these three fully resolved). As such, while raloxifene seems to hold promise, this is definitely not a study that blows away tamoxifen or anything. I’d suggest one could use this data as a source for a ‘step-up approach’. First start with tamoxifen treatment for several months, with an unsatisfactory response one might try out raloxifene.

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs)

The inhibition of aromatase by AIs leads to marked reductions in circulating estrogens. A 25 mg dose of exemestane demonstrates a maximal suppression of estradiol of 62 % 12 hours after intake in young men [11]. When taken consecutively for 10 days, a decrease of 38 % is observed 24 hours after the last administered dose. Increasing the dosage to 50 mg daily does not lead to further suppression. Anastrozole demonstrates similar efficacy. Administration of either 0.5 or 1.0 mg daily for 10 days in young men shows a decrease in estradiol levels of roughly 50 % [12]. Likewise, letrozole treatment (2.5 mg daily) for 28 days showed a decrease in estradiol of 46 % in young men, and 62 % in elderly men [13]. But no idea if this is a statistically significant difference: they didn’t test that. And another trial came with very similar results, showing a 56 % reduction in estradiol in men receiving the same dosage also for 4 weeks [14]. In any case, AIs lead to a marked reduction of estrogen in men. It’s also interesting to have a quick look at how well AIs work in men receiving exogenous testosterone, since these trials I just covered have been performed in men not administering testosterone. There’s little data on this, but one trial examined the effect of combining various dosages of testosterone gel (up to 10 g daily) for 16 weeks in chemically testosterone-suppressed men with anastrozole (1 mg daily) [15]. This trial demonstrated a suppression of over 90 % in the group receiving 10 g daily. (Which led to mean testosterone concentrations of 805 ng/dL, or 27.9 nmol/L.) As such, the suppressive effect on circulating estrogen seems stronger in men who receive exogenous testosterone. It’s hard to say what’s the cause of this. I think it might have to do with the fact that usually a considerable amount of circulating estrogen stems from the testes. The testosterone concentration in the testes is about 100-200 times higher than in the blood circulation [16, 17]. Since AIs bind competitively to aromatase, regular doses of AIs might very well be far from sufficient to be effective in the testes. As a result, only estrogen production in peripheral tissues is suppressed.

But how well do AIs work as a treatment modality for gynecomastia? Unfortunately, only a few trials have examined this, and the results aren’t too promising. A double-blind randomized-controlled trial looked at anastrozole’s efficacy (1 mg daily) in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia [18]. The patients were treated for a total of 6 months, and at the end of the treatment period, only 38.5 % of them showed a reduction of >50 % in total breast volume, whereas 31.4 % of those receiving a placebo showed such a reduction as well. (Note that pubertal gynecomastia in a good amount of cases resolves spontaneously, hence the good response with placebo as well.) No significant difference was apparent between the two groups. However, a partial explanation of anastrozole’s lack of efficacy might be explained by the relatively large number of subjects that had gynecomastia for at least 2 years. This might have rendered them less responsive to endocrine therapy. (Nevertheless, you simply see far better results in similar trials with tamoxifen.)

Another situation in which gynecomastia can develop is in men receiving the antiandrogen bicalutamide in the treatment of prostate cancer. An interesting double-blind randomized-controlled trial assigned prostate cancer patients receiving this antiandrogen to also receive either a placebo, anastrozole (1 mg daily) or tamoxifen (20 mg daily) [19]. In those receiving a placebo, 73 % developed gynecomastia. In those receiving anastrozole, 51 % developed gynecomastia. Notably, in those receiving tamoxifen, only 10 % developed gynecomastia. As such, anastrozole is a poor prophylactic drug for gynecomastia in prostate cancer patients, whereas tamoxifen turned out to be very effective. Other authors found similar results when comparing tamoxifen to anastrozole in bicalutamide-induced gynecomastia [20].

Finally, Rhoden and Morgentaler have reported two cases of gynecomastia in men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy in which treatment with the AI anastrozole was successful [21]. In the first case, a 61-year-old man developed gynecomastia at 6 months after beginning testosterone replacement therapy. After discontinuation, the gynecomastia disappeared within 1 month and the man was able to resume testosterone replacement therapy in conjunction with 1 mg of anastrozole daily without recurrence after 3 years. Similarly, a 30-year-old man developed worsening of his existing gynecomastia after 6 months of testosterone replacement therapy. Testosterone was discontinued and anastrozole was used at 1 mg daily with resolution after 1 month. This man was also able to restart his testosterone in conjunction with anastrozole and reported no recurrence after 5 months. Of course, these are just 2 case studies which have severe drawbacks with regard to extrapolation to the clinic, and I’m mostly noting them for completeness in this article.

So while tamoxifen consistently shows a (very) good response, anastrozole doesn’t under the same circumstances. I’ve been unable to find more data on this, or any data actually on the other two popular AIs (exemestane and letrozole) for the treatment of gynecomastia. However, given their roughly similar efficacy in reducing circulating estrogen, I wouldn’t expect them to differ much compared to anastrozole. I don’t really have a good explanation for the poor response to anastrozole in these trials. Despite its robust decrease in circulating estrogen, this might simply not lead to a sufficient reduction in estrogenic action at breast tissue. It could be this is more pronounced in those who administer exogenous testosterone (or other aromatizing anabolic steroids), since the decrease in circulating is stronger under these conditions. However, no evidence is available with regard to its ability to counteract gynecomastia under these conditions.

Concluding, there is simply very little evidence for the efficacy of AIs in the treatment of gynecomastia. The evidence there is suggests it’s efficacy is poor, whereas tamoxifen shows (very) good efficacy throughout. Finally, raloxifene holds promise but good evidence is lacking. As such, it might be an option in a ‘step-up’ approach after tamoxifen has demonstrated unsatisfactory results.

Surgery

If endocrine treatment fails, there’s always the option of surgery. An important determinant of an aesthetically pleasing result of gynecomastia surgery lies in the size of the gynecomastia that needs to be removed. Since, depending on the size, a different surgical approach might be required.

Small/mild gynecomastia can be removed by means of the Webster’s Method (or with modifications of it) [22, 23]. This approach is pretty straightforward. A semicircular incision is made along the inferior (bottom) inner edge of the areola. This incision then allows the surgeon to remove the breast tissue. This incision is relatively small but can, nevertheless, leave a visible scar. And, if too much tissue is removed, it can compromise blood supply to the nipple and the underlying structural support might be insufficient leaving you with a flat (or even dented in) nipple. Nevertheless, this type of surgery is relatively easy and any proficient surgeon with some experience should be able to do this pretty much flawlessly.

If the gynecomastia is moderate in size, a surgeon might resort to the Letterman technique [23]. Some skin tissue also needs to be removed if the gynecomastia is sufficiently large enough in order to obtain a good aesthetical result. Thus the nipple and areola need to be moved a bit too, and this gives the risk that there might be some distortion of the nipple and areola. And, because there’s some more cutting, you might end up with some more scar tissue compared to the Webster’s Method.

Finally, if your gynecomastia is very prominent, and your breast is hanging as well (ptosis), the surgery is more complex. This requires quite some more cutting and the surgeon will need to create a skin flap with the nipple-areola complex and reposition it [24]. Because of this complexity, there’s a higher risk of achieving a less good result than you would’ve hoped for. And, in case you carry around quite some fat, the surgeon will remove some adipose tissue in the area too.

What’s important here is that, the smaller your gynecomastia, the better your results of a surgery might be. As such, I find it worthwhile to see what tamoxifen does with the size of it if you use it a few months prior to any surgery. Every cm reduction counts. So even if tamoxifen doesn’t fully resolve the gynecomastia for you, or not even close, it might still have helped you with achieving a better result in surgery.

SERM dosages might need to be higher during cycles with testosterone

A final note I would like to make in this article is about the usage of SERMs during an anabolic steroid cycle. SERMs, like tamoxifen, function as a competitive antagonist. That means that they need to “compete” with other ligands of the estrogen receptor, such as estradiol, for binding. Without going into too much detail, that means you need more tamoxifen to occupy the same number (or concentration I should say) of receptors if there’s also a whole lot more estradiol around. Which is, of course, the case when injecting large quantities of testosterone. Concentrations of over 4 times the maximum reference range aren’t unheard of. As such, tamoxifen might be required in higher quantities too to reach sufficiently high concentrations to effectively compete with the increased concentration of estrogen for binding. While under physiological circumstances 10 to 20 mg daily is plenty, one might need dosages of around 40 mg daily while on a high-dosed cycle with an aromatizing androgen. However, this is speculation from my part as there’s no good data on this. But this might help explain why sometimes during an AAS cycle, tamoxifen might not be (sufficiently) effective to prevent gynecomastia from developing.

Conclusions

Tamoxifen is the mainstay treatment modality for gynecomastia. There’s plenty of evidence in the literature demonstrating its (very) good efficacy in the treatment of gynecomastia from various causes. Usually dosages of 10 to 20 mg daily are employed for several months. The drug is well-tolerated and is generally considered safe in this regard. Higher dosages might be required during a cycle, although it’s advisable to always start with the lowest possible dosage. Clomiphene seems ill-suited for the treatment of gynecomastia and raloxifene might hold some promise and could serve as a candidate in a ‘step-up approach’ if tamoxifen is not effective enough. A dosage of 60 mg daily is common in such a case.

There’s scarce evidence of AIs in the treatment of gynecomastia. The evidence there is suggests it’s only minimally effective. It’s unclear what’s the cause of this. It might be more effect in AAS users, as AIs appear to be more potent at suppressing circulating estrogen when administering exogenous AAS. However, there’s simply no data available with regard to its efficacy under such conditions in the treatment of gynecomastia.

Finally, several surgical options exist to get gynecomastia removed. In general, the smaller the amount of tissue that needs to be removed, the better the result of the surgery. Prior treatment with tamoxifen to shrink the tissue as much as possible could thus lead to a better surgical outcome.

Photo by JAFAR AHMED on Unsplash

References

- Nicolis, Giorgio L., Robert S. Modlinger, and J. Lester Gabrilove. “A study of the histopathology of human gynecomastia.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 32.2 (1971): 173-178.

- Mathur, Ruchi, and Glenn D. Braunstein. “Gynecomastia: pathomechanisms and treatment strategies.” Hormone Research in Paediatrics 48.3 (1997): 95-102.

- Narula, Harmeet S., and Harold E. Carlson. “Gynaecomastia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology 10.11 (2014): 684.

- Devoto, C. E., et al. “Influence of size and duration of gynecomastia on its response to treatment with tamoxifen.” Revista medica de Chile 135.12 (2007): 1558-1565.

- Böttner, M., P. Thelen, and H. Jarry. “Estrogen receptor beta: tissue distribution and the still largely enigmatic physiological function.” The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 139 (2014): 245-251.

- Braunstein, Glenn D. “Gynecomastia.” New England Journal of Medicine 357.12 (2007): 1229-1237.

- Mannu, Gurdeep S., et al. “Role of tamoxifen in idiopathic gynecomastia: A 10‐year prospective cohort study.” The breast journal 24.6 (2018): 1043-1045.

- Plourde, Paul V., Howard E. Kulin, and Steven J. Santner. “Clomiphene in the treatment of adolescent gynecomastia: clinical and endocrine studies.” American Journal of Diseases of Children 137.11 (1983): 1080-1082.

- Goldstein, Steven R., et al. “A pharmacological review of selective oestrogen receptor modulators.” Human reproduction update 6.3 (2000): 212-224.

- Lawrence, Sarah E., et al. “Beneficial effects of raloxifene and tamoxifen in the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia.” The Journal of pediatrics 145.1 (2004): 71-76.

- Mauras, Nelly, et al. “Pharmacokinetics and dose finding of a potent aromatase inhibitor, aromasin (exemestane), in young males.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 88.12 (2003): 5951-5956.

- Mauras, Nelly, et al. “Estrogen suppression in males: metabolic effects.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 85.7 (2000): 2370-2377.

- T’Sjoen, Guy G., et al. “Comparative assessment in young and elderly men of the gonadotropin response to aromatase inhibition.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 90.10 (2005): 5717-5722.

- Raven, Garrett, et al. “In men, peripheral estradiol levels directly reflect the action of estrogens at the hypothalamo-pituitary level to inhibit gonadotropin secretion.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 91.9 (2006): 3324-3328.

- Finkelstein, Joel S., et al. “Gonadal steroids and body composition, strength, and sexual function in men.” New England Journal of Medicine 369.11 (2013): 1011-1022.

- McLachlan, Robert I., et al. “Effects of testosterone plus medroxyprogesterone acetate on semen quality, reproductive hormones, and germ cell populations in normal young men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 87.2 (2002): 546-556.

- Roth, M. Y., et al. “Dose-dependent increase in intratesticular testosterone by very low-dose human chorionic gonadotropin in normal men with experimental gonadotropin deficiency.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 95.8 (2010): 3806-3813.

- Plourde, Paul V., et al. “Safety and efficacy of anastrozole for the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 89.9 (2004): 4428-4433.

- Boccardo, Francesco, et al. “Evaluation of tamoxifen and anastrozole in the prevention of gynecomastia and breast pain induced by bicalutamide monotherapy of prostate cancer.” Journal of clinical oncology 23.4 (2005): 808-815.

- Saltzstein, D., et al. “Prevention and management of bicalutamide-induced gynecomastia and breast pain: randomized endocrinologic and clinical studies with tamoxifen and anastrozole.” Prostate cancer and prostatic diseases 8.1 (2005): 75-83.

- Rhoden, E. L., and A. Morgentaler. “Treatment of testosterone-induced gynecomastia with the aromatase inhibitor, anastrozole.” International journal of impotence research 16.1 (2004): 95-97.

- Webster, Jerome P. “Mastectomy for gynecomastia through a semicircular intra-areolar incision.” Annals of surgery 124.3 (1946): 557.

- Rahmani, Samir, et al. “Overview of gynecomastia in the modern era and the Leeds Gynaecomastia Investigation algorithm.” The breast journal 17.3 (2011): 246-255.

- Kornstein, Andrew N., and Peter B. Cinelli. “Inferior pedicle reduction technique for larger forms of gynecomastia.” Aesthetic plastic surgery 16.4 (1992): 331-335.

About the author

Peter Bond is a scientific author with publications on anabolic steroids, the regulation of an important molecular pathway of muscle growth (mTORC1), and the dietary supplement phosphatidic acid. He is the author of several books in Dutch and English, including Book on Steroids and Bond's Dietary Supplements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.