What if Government authorities develop an interest in you? What if they focus on your online activities, and decide to develop a profile on your habits and contacts? They seek to identify your associates through the email addresses of those you’ve corresponded with.

One surveillance approach the Government has used in recent years has been to apply pen registers and trap and trace devices to the Internet. Pen registers are devices that capture the telephone numbers dialed on outgoing calls; trap and trace devices capture the numbers on incoming calls. These devices don’t disclose the contents of the communications, or even whether the parties actually speak – just that one phone dialed another phone. A list of every phone number dialed and the source of every call received can establish a comprehensive profile of a suspect’s contacts, affiliations and activities. Think about how useful these devices are in the investigation of racketeering conspiracies: “Hey, the target calls a number registered to ‘Jimmy Potts’ twice a day. Let’s do some surveillance on this guy Jimmy and see what develops…”

It’s been estimated that federal law enforcement agencies conduct roughly ten times as many pen/trap surveillances as they do “Title III” wiretaps (the kind that allows them to listen to content, such as by bugging rooms or eavesdropping on phone conversations). The beauty of pen/trap surveillance to law enforcement is that, unlike wiretaps, they can be obtained very easily. The Government simply has to certify to a judge that the information likely to be obtained by the surveillance is relevant to an ongoing criminal investigation – even if the target is not a suspect in that investigation. By comparison, for the Government to get a Title III wiretap, they have to meet the high standard of showing probable cause to believe that the target committed one of a list of severe crimes. So, pen/trap surveillance can help the Government fish around for evidence against people it has no proof against. Also, the feds don’t need to report their findings back to the court like they have to with traditional wiretaps, so there’s little chance of oversight of potential abuses.

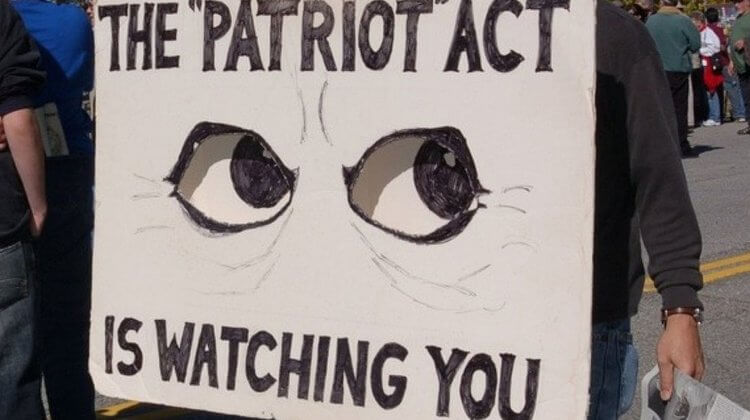

Before the USA PATRIOT Act (Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115 Stat. 272 [Oct. 26, 2001]), some judges were already authorizing the use of pen/trap surveillance to capture the source and destination information for emails. But the PATRIOT Act furthered things along by explicitly applying pen/trap surveillance to the Internet by federal statute. While it does not permit the feds to read any of the contents of the emails, including the subject line, with a pen/trap order, it can be argued that pen/trap surveillance on the Internet is more intrusive and personally revealing than on telephones because email addresses are unique to individual users while many individuals may share one telephone number. Further, there remain serious questions in situations involving Web “addresses” and other URLs identifying particular content.

The PATRIOT Act also diminishes online privacy by changing the law to increase how much information the Government can get about Internet users from their Internet Service Providers (ISPs) or others who handle and store their online communications. It allows ISPs to voluntarily turn over all “non-content” information to Government agencies without a court order or subpoena. It also broadens the types of records that the Government can seek with a subpoena and without a judge’s review.

All in all, while the PATRIOT Act may be terrific when applied to combat terrorism, some of you may not like it in other contexts. For example, if Congress passes the proposed amendments to the Anabolic Steroid Control Act, will the suggested harsher treatment for steroids and prohormones motivate the Government to monitor those they may suspect are conducting transactions online? In the absence of comprehensive judicial oversight, just how expansively might the Government apply this law?

About the author

Rick Collins, Esq., J.D. is a principal in the law firm of Collins Gann McCloskey & Barry PLLC, with offices on Long Island and in downtown New York City. He is nationally recognized as a legal authority on anabolic steroids, human growth hormone, and other performance-enhancing substances.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.