While the participation of women in sports has increased significantly over the last several decades, research of women in sports has lagged behind that of men. This is particularly true in matters related to reproduction and menstruation. Up until even recent years, women were cautioned not to partake in sports while pregnant or during menstruation because exercise during these times was thought to be detrimental to a woman’s health. While there certainly are precautions recommended for pregnant women, recent studies show that modified participation in exercise and sports activities is beneficial. As well, menstruation has become less of a roadblock in achieving sports goals for women. Nevertheless, there is still much we do not understand regarding women and gynecological issues.

Menstruation has historically been a taboo subject in sports science and between coaches and female athletes. Embarrassment and lack of empathy by a male-dominated field have often surrounded the issues. As well, any woman who is old enough to be acquainted with the pre-tampon days will remember how inconvenient menses were while swimming or during a sports match. Since the late 1950’s, improvements in feminine hygiene products facilitated increased participation of women in exercise and sports. We now see women active in all aspects of exercise and competing in sports alongside their male counterparts.

Although there is abundant research addressing how exercise affects menstruation (see previous column “Female Athletes and Menstrual Irregularities“), less is known about how menstruation affects women’s performance in exercise and athletics. These cyclic hormone changes can affect physical and psychological potentials and ultimately influence sports performance although experiences are highly individual. This article will look at some of the research on how exercise performance is affected by the menstrual cycle and include anecdotal observations reported by women athletes and coaches.

The Menstrual Cycle

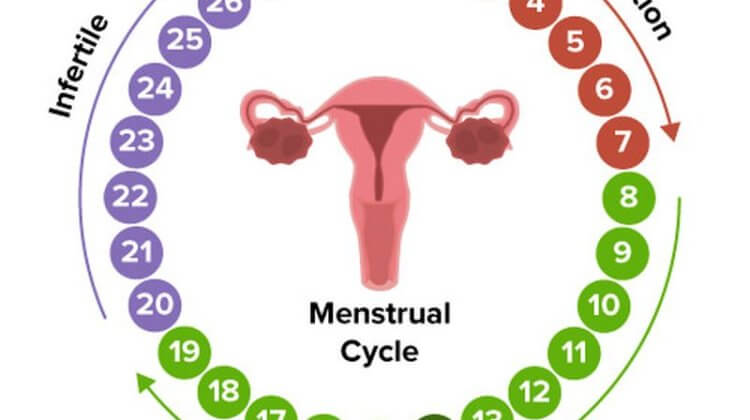

Before we can address the topic, readers need to have a clear understanding of the major phases of the menstrual cycle. The typical menstrual cycle is 28 days long, with the first day of menses (shedding of the uterine lining) considered Day 1. Menstruation is usually completed by Day 5, and the mucosal lining (endometrium) of the uterus once again begins to proliferate in preparation for an egg. The phase from Day 1 to ovulation, which is normally Day 15, is called the follicular phase. The luteal phase is from ovulation until the day before menses, normally about Day 28. The terms follicular and luteal phases are used most frequently in the literature and will be used in this article.

Steroid hormones, most predominantly oestrogen and progesterone, regulate the various phases of the menstrual cycle. These hormones in turn are regulated in a complex feedback system by luteinizing (LH) and follicular stimulating (FSH) hormones secreted by the pituitary gland. And so the cycle continues from the beginning of the first menses until menopause.

As most women know, symptoms that accompany menstrual cycles vary considerably. Some women do not experience any symptoms; others may suffer slight discomfort to severe pre- or initial-flow discomfort. Changes in exercise performance during the menstrual cycle are also variable. Many women report impaired performance and many do not. There are a number of women who have won Olympic medals while menstruating. Some women may experience some minor discomfort but merely push themselves forward during participation. Let’s take a look at what the research reports and at some of the observations by coaches and female athletes.

The Research

Most exercise physiology texts state that menstruation does not affect athletic performance. However, if you talk to female athletes, many report some differences, ranging from symptoms of low back pain to increased fatigue. Granted, there are few controlled studies on the topic and most of the information found is based on subjective reports. To add to the confusion, the published studies are often times conflicting. Some studies report that performance is enhanced during the follicular phase, while others report it is best during the flow phase. Poorer performance has been reported in more endurance-type activities during menses. Conversely, winning performances in swimming and track-and-field have occurred during menses.

Lebrun (1) published a comprehensive review of the literature examining the effect of menstrual cycle phase on athletic performance, citing the inconsistencies in the surveys, methodologies, and lack of substantiation of cycle phase. According to an analysis of the surveys, most female athletes (37-67% of those polled) did not report any detriments, while a minority (13-39%) reported improvements during menstruation. Some studies report differences during the cycle phases with best performances during the intermediate postmenstrual days and worse performances during premenstrual and initial-flow days.

Although study results vary, some show that metabolic and cardiovascular responses during submaximal and maximal exercise are not systemically affected during different phases of the menstrual cycle. One study reported no changes in fat and carbohydrate utilization during exercise performed throughout the menstrual cycle. Yet another study demonstrated that glycogen repletion after exercise was greater during the luteal phase than the follicular phase. The results of the second study suggest that muscle glycogen content may be enhanced during the luteal phase. A further study investigated the effects of a 24-hour low-carbohydrate diet on responses during prolonged exercise in both phases of the menstrual cycle. A significant decrease in blood glucose levels was observed after 70-90 minutes of medium intensity (63% VO2max) exercise during the luteal phase. This study, as well as others, documents variations in plasma electrolyte concentrations during the menstrual phases, with sodium, potassium and chloride higher during the follicular phase and falling significantly during the luteal phase. Bicarbonate levels were also lower in the menstruation days and during ovulation. Whether these findings ultimately affect performance is not clear. However, it may account for consistent reports of increased fatigue during the menstrual phase.

Additionally, several studies demonstrate reduced reaction time, neuromuscular coordination and manual dexterity during the pre-menstruation and menstrual phases. Considering there is evidence that blood sugar levels, breathing rates and thermoregulation vary during the menstrual cycle, the slight decreases in aerobic capacity and strength reported by some women may indicate physiological bases for some women’s observations.

The most consistent reports are effects of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) on exercise performance. Nearly all women are familiar with symptoms of bloating, headaches, fatigue, and cramping during the late luteal phase. Many studies relate an increase in perceived exertion during premenstrual and early menstruation days. As well, several authors reported that effects of PMS could alter performance as the tasks increased in difficulty and complexity. Others note impairments in exercise performance arise from breast tenderness, abdominal constriction, and fatigue.

Also reported in some of the literature is an increase in musculoskeletal and joint injuries during this time of the menstrual cycle. However, there is little definitive research indicating the exact causes. One theory is a relationship of increased relaxin levels and increased flexibility and elasticity of connective tissue, such as in articular joints. Relaxin is a hormone that is thought to be responsible for softening and relaxation of the ligaments in various joints. Although still poorly understood in humans, relaxin levels highly correlate with relaxing of the pubic bones allowing for birth in females of several mammal species. Relaxin is thought to create joint laxity, which allows the pelvis to accommodate the enlarging uterus. This may also weaken the ability of supports in the lumbar spine to withstand shearing forces. In the pelvis, joint laxity is most prominent in the cartilage between the two pubic bones and the sacroiliac joints.

Relaxin secretion has been shown related to ovulation, with increased levels about 6 days after LH peak. Significantly high levels were detected in women using oral contraceptives, possibly due to induced changes in relaxin secretion. Several studies associate high levels of relaxin with low back pain in women during pregnancy, and similarly high levels in non-pregnant women with posterior pelvic pain. Although there is no investigation in the role of relaxin in sports injuries in wome, there may be a correlation.

While women secrete considerably less androgens than men, they may still play a role in women’s physiological status during training. Androgens are important for increased red cell production, bone density, increasing muscle synthesis, and alleviating fatigue. Plasma testosterone in women normally fluctuates throughout the menstrual cycle with peak levels around ovulation. Some female athletes report increased strength during this time, but this has not been substantiated in studies.

As previously stated, there are many inconsistencies in the information available due to the numerous variables (nutritional status, fitness level, degree of exercise, mood state, etc), different methodology and small numbers of women studied. We know that physiological functions fluctuate, sometimes widely, throughout the menstrual cycle. Obviously, with some of the reported physiological changes during phases of the menstrual cycle, athletic performance could potentially be impaired or increased. Interestingly, none of the literature has associated any physiological fluctuations or athletic impairment in women who are on oral contraceptives. Of course, this aspect has not been investigated thoroughly, so conclusions should be made with caution.

Anecdotal observations

Nowhere in the literature is there such a thorough presentation of female athlete’s testimonies on the influence of the menstrual cycle as in Judy Daly and Wendy Ey’s book “Hormones and Female Athletic Performance” (2). The authors have compiled testimonies by many female athletes, many whom are Olympic medal winners. Many women reported impairments in their training and performance, mostly due to premenstrual symptoms. As well, several women reported increased incidence of injury during the premenstrual week.

In my own informal survey (with limited numbers of women and coaches), I have found about an equal response of impairment and no interference of menstrual cycle on exercise performance. The most common observation is increased fatigue during premenstrual and initial-flow days. Another comment some women have made is general lack of energy during the early days of menstruation and PMS- associated low back pain. A few female endurance runners have noted decreased aerobic capacity as well.

A physical therapist I spoke with that works with many athletes related a high incidence of musculotendon and joint injuries amongst women athletes. He observed that many of his female athlete patients complained of low back tenderness or pain, mostly confined to the sacroiliac joint, during the premenstrual phase. A few coaches I have corresponded with also report complaints from their female athletes of periodic low back pain. Some coaches modify their female clients weight training during phases of their menstrual cycles.

Strength training

We have thus far discussed the influence of the menstrual cycle on general performance of athletes and in exercise. Let us now examine how this relates to women and strength training in more detail.

There are few studies that specifically investigate the effects of the menstrual phase on strength training. One study reports no statistical significance in physiological and subjective responses to lifting during the various phases, except for a slight elevation in heart rate during the post-ovulatory phase. However, subjects were only required to lift a weighted box from knee to shoulder level at six repetitions for 10 minutes.

Another study measured maximum voluntary isometric force of the quadriceps and handgrip by electrical stimulation. There was an increase in quadriceps and handgrip strength at mid-cycle, but what relevance this has on real training is questionable. Additionally, no variation in strength due to menstrual status was found in a large survey of women aged 45-54 years by measuring isometric handgrip, quadriceps strength, and leg extensor power.

The effects of two different training programs for women were compared which altered the frequency of training sessions. Regular training consisted of a training session every third day over the entire menstrual cycle. The other approach, menstrual cycle triggered training (MCTT), incorporated training sessions every second day in the follicular phase and once per week during the luteal phase. Subjects performed three sets of 12 repetitions each to increase maximal strength. Measuring body temperature, LH peak, and analyzing plasma levels of hormones and sex hormone binding globulin determined cycle phases.

The MCTT resulted in an increase in maximal strength (32.6%) compared to the regular training (13.1%). Muscular strength was significantly increased during the second menstrual cycle, with all subjects showing high strength adaptations. There were significant correlations between force parameters and the accumulation of estradiol. The authors found that the MCTT was more efficient compared to the regular training program.

Charles Staley, sports strength and conditioning coach, reported to me that he noticed a similar pattern that was consistent in his female athletes. He modified his female strength athletes’ training to correspond with the volume fluctuations in the above study and observed an improvement that prompted him to continue with the modifications.

A coach who trains women for powerlifting related to me that he reduces intensity and volume during the week before and a few days into menstruation. He integrates low rep sets or decreases the weight load in order to compensate for increased fatigue and to preserve joint integrity.

From my own experience as a powerlifter, I suffered a connective tissue injury twice in the sacroiliac region while lifting heavy during dysmenorrhea (abnormally frequent menstrual flows). A sports orthopedist and two physical therapists that treated me commented that it was very likely connected to abnormal hormone levels and effects on the connective tissue. The historical observation that I normally experience low back pain during the premenstrual phase may lend evidence to the influence of hormone fluctuations on my athletic performance.

Summary

While many studies that measured physiological responses of the menstrual cycle in women during exercise found no performance changes, any changes most likely depend on the individual and her specific conditions. Some women suffer more from cramping, PMS, or heavy bleeding than others and thus may impact their performance.

Several coaches suggest their female athletes log their menstrual cycle and associated physical and emotional states. They can also chart their exercise and athletic performance to establish strongest and best training days and when they are impaired. This will facilitate modifying a training schedule by planning for strenuous sessions, peak training and when rest is needed. Factors that can be altered are volume (number and duration of repetitions), intensity (speed and load), and difficulty (skill level and injury risk). Nutritional considerations should also be factored to optimize recovery and fuel stores. Considering that testosterone peaks around ovulation, it may be beneficial to plan for peak strength training loads at this time.

It is important for athlete and coach to remember that all athletes are individuals and may respond differently. A master plan may not work for all. Careful record keeping and modifications in training if needed may increase performance and reduce risk of injuries. In today’s increasingly competitive sports field, this may become important to achieve athletic excellence.

References

1. Lebrun CM. Effect of the different phases of the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptives on athletic performance. Sports Med 1993, 16(6):400.

2. Daly J and W Ey. Hormones and Female Athletic Performance. Women’s Sport Foundation of Western Australia, Inc., 1996.

About the author

Elzi has spent the last several decades trying to determine where 'home' is: from New York, Maine, California, Oregon and now Texas. As well, her career has encompassed tool & die apprentice, forest ranger, assistant extension agent, mother, sheep and horse rancher, and mad research scientist. She has also been a competitive bodybuilder, but has found true joy in powerlifting. When Elzi is not playing fetch with her 1200 lb four-footed buddy, she is most happy in the gym and in a research lab.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.