Prologue

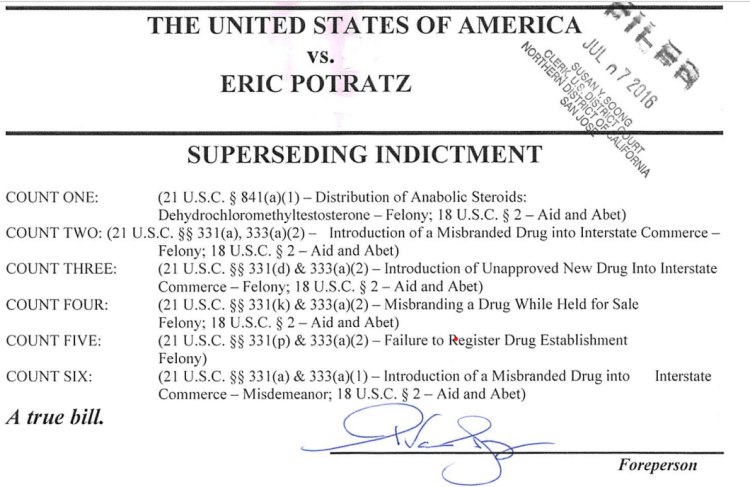

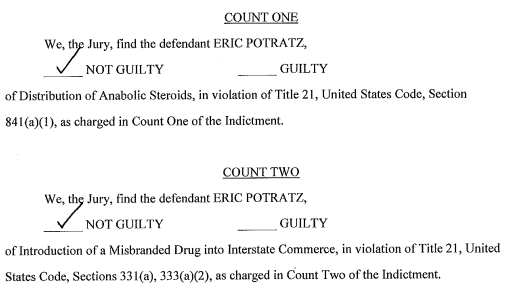

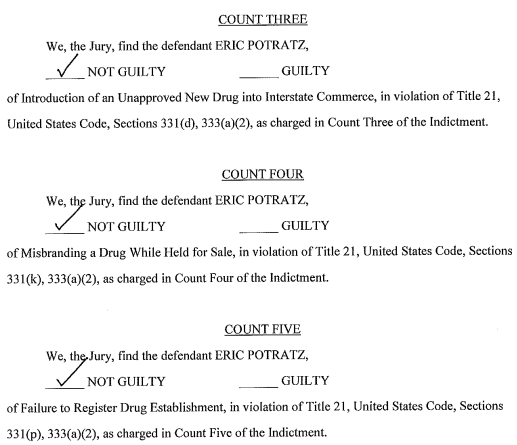

On the Eighth of February 2010, a federal criminal investigation was opened into a prohormone company. The government had been tipped off by anti-doping authorities and tapped the most famous anti-doping agent in the world to investigate. The investigation led to undercover work and eventually a raid. The government waited for the seized products to expire before performing chemical analysis on them – well past the stage when a reasonable chemist would know that impurities would develop. The investigation continued for years. Right before the statute of limitations expired, after untold taxpayer dollars and federal law enforcement resources had been spent, an indictment was finally unsealed. The superseding indictment charged the owner of the company with numerous steroid-related crimes, based on these impurity levels. The impurity levels that were only present after the products had long expired, and not while they were sold by the defendant. A trial followed the indictments. A jury verdict of not guilty on all counts followed the trial. But the company folded anyway, financially, and publicly crushed by a textbook example of prosecutorial overreach.

This is the story of Primordial Performance. But it’s also the story of many other companies who have been destroyed, not through a jury verdict of guilty, but through simply being prosecuted. Some, perhaps most, staring down the barrel of the very real possibility of a decade—or more—in prison, take a plea deal right away. Because what these defendants inevitably discover (too late) is that dietary supplements are primarily regulated through a strict liability/vicarious liability system. This system allows a CEO to face criminal charges for violations of which they were unaware (strict liability), so long as the crime was committed by someone employed by the company (vicarious liability).

I also have firsthand knowledge of similar cases and can assure you that what seems to be an outlier or mistake, because you never see it happen on TV or movies, actually happens with sufficient frequency to establish a pattern. As I’ve said, this isn’t just the story of one supplement company, and I’ve endeavored to present as many details as possible that overlap with the majority of steroid/supplement cases.

***

The Food and Drug Administration Office of Criminal Investigation opened their case into Primordial Performance, and owner Eric Potratz, as a direct result of a United States Anti-Doping Agency email sent in February of 2010. The email contained Primordial’s advertising of a Superdrol (more properly known as methyldrostanolone) clone and a USADA representative whining about it being for sale (note that methyldrostanolone was made a controlled substance in on the 23rd of November 2011, a year and a half after this email). As the investigation progressed, there was no doubt that Primordial Performance was selling steroids. In fact, I think their slogan was basically “We sell steroids for men.” But remember, not all steroids are controlled substances, and not all are prohibited as dietary supplements. (Dehydroepiandrosterone, or DHEA, is a legal-for-sale anabolic steroid, due to a specific exception carved out of the Controlled Substances Act).

The investigation originally focused on Supedrol followed by trendione. Primordial Performance had indisputably sold both. But like methyldrostanolone, trendione was not added to the official list of controlled substances until much later (December of 2014, with the Designer Anabolic Steroid Control Act). Trendione was only made (legally speaking) a controlled substance well after Primordial had sold their final stock. The same goes for methyldrostanolone. This is basically how the investigation unfolded – various steroids, that were not yet controlled substances, and were no longer in stock, were the focus of the investigation. I’ve seen this more than once, and from a utilitarian sense, I can’t imagine why anyone would prosecute behavior that ended years ago and shows no signs of recurring. I don’t claim that dietary supplement crimes shouldn’t be prosecuted. I claim that crimes involving the public health ought to be prosecuted when they are (potentially) still a threat, not when they’ve concluded. Controlled substance (distribution) crimes, on the other hand, ought to be prosecuted after the substances in question are actually controlled, and (in my estimation) only when they present an actual danger to the public or public health threat. The substances catalyzing the investigation into Primordial meet none of these criteria.

In August of 2011 (again, before methyldrostanolone and trendione were added to the government’s list of illegal anabolic steroids), the FDA OCI agents overseeing the case met with two Assistant United States Attorneys to discuss one of the other substances thought to be a steroid. This steroid in question, like Methyldrostanolone and trendione, was not listed anywhere in the Controlled Substances Act. At this point, reading through the FDA OCI agent’s case notes, one begins to get the feeling that they know they’ve wasted their time and are not trying to find something…anything…to prosecute.

Adding to the DOJ’s prosecutorial burden was the fact that one of the FDA’s own top scientists disagreed with the Special Agents and Attorneys as to the legality of the steroid in question. Dr. Robert Moore, of the Division of Dietary Supplement Programs, believed the substance at issue was a metabolite of DHEA. As such, he opined that it was legal for sale. While metabolites of legal substances may qualify for sale under DSHEA, salts, esters, ethers, and analogues of illegal substances may be controlled. But this was the former, and clearly not the latter, meaning FDA OCI was SOL.

Until this point, the DOJ had presumably (based on the context of the internal documents) thought the substance was an anabolic steroid. Oops. A government scientist is saying part of the prosecution’s case is scientifically and legally unsound. Whatever should the government do? Counting methyldrostanolone, trendione, and the DHEA metabolite, none of the stuff being sold by Primordial Performance would have been prosecutable as an anabolic steroid at the time of the raid. The FDA had taken possession of Primordial’s entire stock, multiple bottles of the full product line (14 products), and securing a conviction under a controlled substance charge was starting to seem unlikely, bordering on impossible.

Subtract the potential controlled substance charges and prosecute the same crimes as FDCA violations (a layup) and the maximum would be 36 months, with probation being the more likely outcome. That’s a lot of leverage to lose in terms of hammering out a plea deal and a strong inference could be made that at least some prosecutors charge the harshest crimes possible intending to gain a stronger negotiating position for a plea deal. The prosecution, you see, doesn’t have to provide the defendant with full discovery (access to the evidence supporting the charges) while negotiating a plea deal. Frequently, the defendant doesn’t know exactly what evidence the prosecution has in its possession and is pressured to make a blind deal in that regard.

Ultimately, the government tested every product seized from Primordial (14 in total) and found that one was contaminated with traces of a scheduled substance. Actually, it was a contaminant found in even the purest reference samples. Therefore, when the most sophisticated labs in the world attempt to make the ingredient, at the greatest possible purity, it’s still contaminated with a controlled substance. This is not uncommon. Most (if not all) of the DHEA products you find on the shelves in every drug store, are contaminated with controlled substances – I’ve seen the lab tests.

But despite the fact that contaminants are a natural by-product, and not actually spiked (intentionally added) by the manufacturer, the government tried to prosecute on this evidence. The DOJ based their entire prosecution around a single contaminated product, from which they charged six separate counts. Errr…I mean five separate counts. Right before trial the government dropped a count from the superseding indictment. Was that count only there to serve as leverage in a plea bargain scenario?

If so, it would have been unnecessary. In these types of cases (most cases, really) the government, and its agents, are each in the best of a heads I win/tails you lose scenario. Simply the will to prosecute ensures in most cases that even a not guilty verdict will bring about the wreckage of a(ll but the most wealthy) defendant’s life. Much of the time, a plea deal is, in a utilitarian sense, the most sensible option. Sometimes a guilty plea can be cheaper than a not guilty verdict, and even cause less damage to the defendant’s life and career. Some damage, due entirely to the DOJ’s tactics, will be irreparable for most.

Have you ever seen a press release on the DOJ website talking about losing a case (i.e., a defendant obtaining a not guilty verdict)? I bet not. Because they don’t exist. The DOJ exclusively posts notice of their allegations and victories (an indictment followed by a plea or guilty verdict); they’ve got no interest in posting the truth when a defendant is vindicated. Therefore, even if you win, they’re not taking down (or updating) their original press release(s) announcing your arrest and indictment, nor any of the updates (i.e., a co-conspirator being found guilty or taking a deal). For most people this will be the top Google hit for the rest of their lives. The DOJ press release announcing your indictment will probably be the first thing future employers are going to find moving forward, for the rest of your life.

The average citizen could not afford to defend themselves in either a civil or criminal setting. Because of the mechanics involved with prosecuting supplement companies, very few of them can afford it either. Primordial had virtually all inventory seized, and despite the favorable jury verdict, none of it was ever returned. I’ve seen, in every instance where the government has seized dietary supplements, even totally legal ones, a concerted effort to keep all seized products. The government will literally file motion after (fruitless) motion to deprive the rightful owner of taking possession of their seized dietary supplements. In fact, the government used the fact that post-trial they hadn’t returned, nor disposed of, the seized inventory as a reason to declare the case “still open” and not turn over the appropriate documents per my Freedom of Information Act requests.

The dubious tactic of seizing inventory from dietary supplement companies also serves to run out the clock on their ability to stay in business. Most dietary supplements have an expiration date of two years; the Primordial case took so long that the inventory expired and could no longer be sold before the indictment was filed. As it was “evidence” (of a crime that never happened), it could not be returned. Sizable financial loss is baked into the execution of search warrants whenever a supplement company is raided. This loss is often hundreds of thousands of dollars, and that’s not lost because an indictment was filed and the defendant found guilty, it’s simply because the government executed a search warrant. With no more cashflow resulting from no more inventory, supplement companies usually can’t survive a raid, nor continue operating until a trial that may be several years away.

The pre-charging phase is enough to qualify as punishment by any reasonable definition. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars are lost overnight when a supplement company is raided and products seized. All of that is before a defense attorney gets hired, and that’s well before that newly hired attorney tells his client about the expert (or investigator or researcher or whatever) he always uses for cases like this, ubiquitously adding “he’s expensive but worth every penny,” (all personnel suggested by an attorney, for any role on any trial team, will have this qualification). Prosecutions, even unsuccessful ones, will bankrupt (or at least drain entirely) most supplement companies on the small to mid-tier level, and will almost always bankrupt their owners as well. Primordial Performance no longer exists, and the owner had to rely on a public defender; cost for the expert witness hired to testify on behalf of the defense was in excess of $28,000. He was worth every penny…which should make you, dear reader, quite pleased, since taxpayer dollars went into paying his salary (as did they go into paying for this entire prosecution and defense).

Much can be said about the so-called “battle of experts” seen in these types of cases. Frequently, in a large proportion of cases (both civil and criminal), the battle of experts is enough to noticeably tip the scales in favor of one side over the other, and reliably predict the eventual outcome. Consider this briefly: the bill for one expert witness would empty most American’s entire savings account. And that’s just one witness — an entire defense team, paid throughout trial could easily run from 10x that number into the millions of dollars. Basically, in drug cases similar to Primordial, each side puts their own scientist (frequently the DOJ relies on DEA or FDA scientists who don’t get paid extra for the specific casework) on the witness stand, and that scientist testifies that the substance in question is (or is not) a drug, scientifically speaking, because it does (or does not) meet the following criteria…yes, I’m serious.

Two scientists (typically PhDs) will each, straight-faced, tell a jury that as a scientific matter they’ve come to the precise opposite conclusion of the other scientist, who often has the same credentials, and while both are looking at the same chemical substance. Chemistry, recall, is a science like any other. We can no more believe that two chemists can have legitimate disagreement over established fact(s) than we could believe that two mathematicians could disagree about the sum of two plus two. But doesn’t scientific opinion feel like two words that shouldn’t go together?

An expert witness for the purpose of a jury trial is when someone who has scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge, gives his or her testimony based on sufficient facts produced by reliable principles and methodology, as applied to the case at hand. How does that produce an opinion? For cases like Primordial (and moving forward, for all designer steroid and/or analogue cases) the DEA doesn’t publish their scientific methodology, and they meet in person as a committee (without taking notes) to arrive at their opinions, so we’ll never know. Nobody knows if their methods are (or were) reliable or repeatable, and their internal library of scientific work is evergreen (meaning they can change it whenever they want, without keeping the prior work). It’s almost like their whole process is designed to produce nothing of use to a defendant, and furthermore to shield their experts from peer review and outside experts punching holes in their work. In fact, a neutral committee of experts was once formed to standardize this exact area of science/law to produce reliable and consistent results, but the DEA refused to participate. You should be able to draw your own conclusions about this refusal (and many more about what kind of scientists are employed by the DEA).

The $28,000 expert witness fee paid by the defense appears to have been worthwhile, and the DOJ who didn’t hire any experts…well, they got what they paid for. The FDA attempted to prove that Primordial had been selling steroids, based on finding a single contaminant in a single product. The contaminant was present at many times the projected ratio viz a viz the intended ingredient. But that product was tested well after it had expired and prior tests on the same product (performed by a third-party for the manufacturer in 2010) showed exactly the opposite. The prosecution filed a motion and gave oral arguments to have that exonerating evidence excluded from the trial. Think about this for a moment. The prosecution tried to have legitimate scientific data, not produced in anticipation of trial (i.e., with no chance of having been intentionally tainted), excluded from the jury’s consideration. Proof that the defendant was almost certainly innocent was almost not shown to the jury because the prosecutor wanted to hide it. When the product was actually on the market and being sold by Primordial, it contained the ingredient it was supposed to, and only a trace amount of the contaminant.

The Primordial case, however, was not entirely won by experts, scientists, or even lawyers. I believe, after reading hundreds of pages of court documents, plus all relevant “Law Enforcement Eyes Only” documents I’ve obtained through years of FOIA requests, that this case was lost entirely on agent testimony. Sometimes it just comes down to the jury and who they find more credible. To that end, the prosecution attempted to stack the deck against the defendant by excluding all dietary supplement users (a category that includes most United States citizens) from serving on the jury. From there, the prosecution made no effort to conceal the star power behind one of their witnesses. This Special Agent, the prosecutor told the jury, was the lead investigator on the highest profile steroid bust in United States history. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this man knows steroid dealers and steroid dealing…That brag helped destroy the prosecution’s case.

The prosecution had inadvertently opened the door for the defense to begin pointing out the differences between a dietary supplement company (like Primordial, perhaps mistakenly selling products they shouldn’t have) and an actual steroid dealer. When the defense attorney cross examined this same witness, it was a surgical takedown of the prosecution’s entire case. Oh, you’ve busted steroid dealers before? Did they openly disclose their real names online, saying they sell steroids? Did they do interviews about their steroid products? Did they put their name and face on the company along with the word “steroids”? Oh, so there’s nothing about this case that resembles an actual steroid bust. Thanks, no more questions.

The guy who took down the most famous steroid ring in the world (at the time) was forced to admit that the defendant did not act like a steroid dealer, and the jury appeared to believe that nothing about his behavior appeared to contradict the fact that he was, at all times, (of the belief that he was) selling legitimate dietary supplements. This was a huge problem to the prosecution, because the controlled substance charges all have an intent prong; the defendant must intend to violate the law.

Reading the rest of the testimony of this FDA OCI agent, as he explained anabolic steroid laws to the jury was excruciating. It was more like a description of how he wanted the laws to be or how they’d have to be for them to win the case. Without exaggeration, it would be difficult to extract a single point of testimony where this Special Agent accurately conveyed the applicable law to the jury. But this still isn’t where the case was lost. A better grasp of the law might have prevented this botched prosecution, but it’s not where the case was lost.

The case slid completely out of the prosecution’s grasp when each FDA OCI special agent (all three), cross examined about exculpatory evidence, displayed a remarkable case of temporary amnesia. Imagine the jury’s shock, when the Special Agent who literally remembered every piece of damning evidence against the defendant, failed to remember a single piece of evidence that would have helped the defendant. Now imagine the jury’s shock when three agents, plus the prosecution’s civilian fact witnesses, all played the same game of remembers everything/forgets everything (also known as play stupid games/win stupid prizes). Due to something called the “Jenks Act,” the prosecution is not required to provide (fact) witness statements to the defense until after they’ve testified. Again, this helps the prosecution to negotiate a plea deal because the defendant doesn’t know exactly what certain witnesses have said during their interviews (or interrogations, as the case may be).

And if the case was nearly lost based on agents’ testimony, then a natural corollary is that it was pushed over the goal line by Eric Potratz’s testimony. Most defendants are best served by not testifying in their own defense. Not Eric. He’s what I call a True Believer. Although he and I (probably) have some legal or scientific disagreement about the ingredients he had been selling – he did not lie (say something he believed to be false) even once during his testimony. Did I think, at some points, he was wrong? Absolutely. And to be fair we are talking about products (in some instances) sold over a decade ago. I have no doubt that his knowledge base has increased since then, and whatever mistakes he potentially made with those products would not be made today. But my opinion isn’t relevant as to whether he was credible (I wasn’t on the jury) and from reading the testimony, I came away with the opinion that he wasn’t being deceptive. He wasn’t making things up. He wasn’t ducking questions. And furthermore, I think he told the truth when he was served with the search warrant and agreed to speak with agents on scene (note: never do this, even if you’ve got nothing to hide).

In a hundred and fifty thousand emails, 600gb of files, the prosecution failed to produce a single piece of evidence, or aggregate of evidence, to convince the jury to hand down a guilty verdict. The most compelling piece of evidence they produced was a lab test on a single expired product, and testimony from government agents and scientists that made me cringe to read. Not surprisingly, the jury found Mr. Potratz not guilty on all counts. But the damage was done, and Primordial was out of business, despite having done, in the eyes of a jury, nothing that the prosecution claimed to be illegal.

End Notes:

I know the owner of Primordial Performance and have known him since before he officially went live with the company. I also know one of the investigators on his case (yes, a government agent). I’ve spoken to both, but I’ve also pulled court documents and filed successful Freedom of Information Act requests that dragged on for years. The defendant’s attorney has failed to return repeated emails. I have not spoken directly to the government attorney in this matter, repeated emails have bounced, and he does not have active social media accounts.

My Freedom of Information Act work on this case may be found at MuckRock:

Select court documents for this prosecion may be found at Court Listener:

https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/6196877/united-states-v-potratz/

About the author

Anthony Roberts is an expert in the field of performance and image enhancing drugs. He has authored books ranging from the pharmacology of anabolic steroids and growth hormone to their illicit use and trafficking. His writing can be found in magazines such as Muscle Evolution, Muscle & Fitness, Human Enhancement Drugs, Muscle Insider, and Muscular Development.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.