Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

Table of contents

Introduction

Bodybuilders commonly talk about themselves, and each other, as ‘monsters’. At first, I didn’t think much about this, as I thought that this was just a reference to their size. But lately I have been thinking that maybe there is more to bodybuilding monstrosity than their sheer bulk.

Bodybuilding monsters: Real and self-made

For a bodybuilder to be called a ‘monster’ is the ultimate compliment. Some might even say that monstrosity is the aim of bodybuilding.

Most of the time when academics, like myself, talk about monsters they are talking about fictitious monsters: the monsters that appear in folktales, and in the belief systems of other cultures.

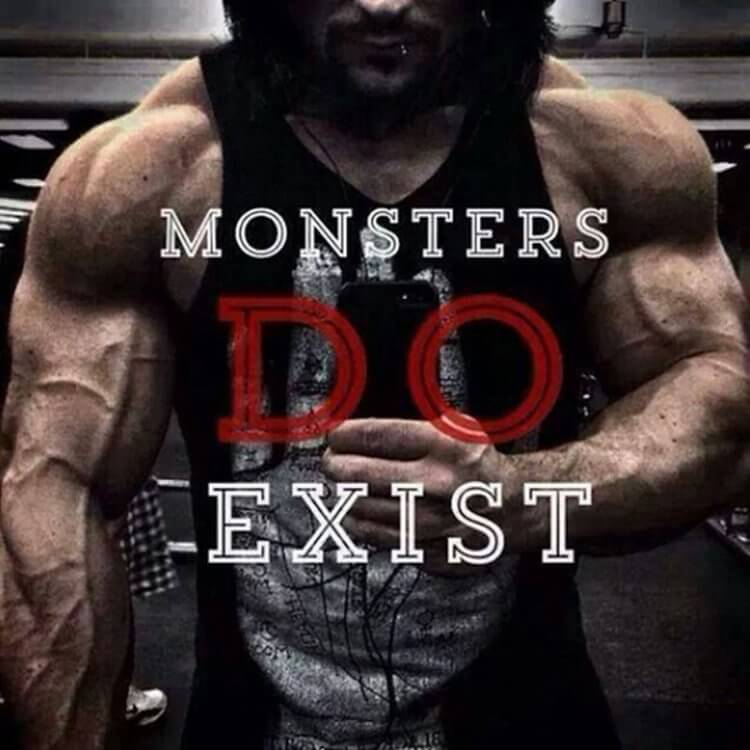

But in bodybuilding monsters are made real. Indeed, approximately 90% of the 38900 Instagram posts tagged #monstersdoexist are photos of bodybuilders (of the remainder the majority are of large animals such as deer or fish, or individuals in costume).

When academics examine real monsters, it is typically people who have been deemed monsters by other people (e.g. anorexics, trans people, the freaks of the 19th C freak shows). There are very few people who self-identify as monsters, for example, Lady Gaga and her fans (aka ‘Mother monster’, and her little monsters), some performance artists such as Orlan and Stelarc, and perhaps the most conspicuous monsters on the planet: bodybuilders.

Bodybuilding is a deliberate process of monstrification.

Monstrosity as branding

Monstrosity has also become a central aspect of bodybuilding branding. A bodybuilder can buy supplements from companies such as Monster Supplements, or Supplement Monster, and those supplements could be Monster Test Testosterone Booster, Monster Aminos, Monster Pump Preworkout, Monster Shred Preworkout, Anabolic Monster Beef Protein, Monster Muscle Protein Powder or Muscle Monster Mass Gainer. They can increase their energy and protein consumption with Monster Muscle Energy Protein Shakes, and buy enhancement drugs from Monster Steroids or Monster Gear. They could then motivate themselves with the numerous YouTube videos titled ‘Monster Project’ or ‘Project Monster’, before going to train at Muscle Monster Gym or Monster Fitness, whilst wearing Monster Factory clothes, and do Dumbbell Monster, Monster Maker or Monster Muscle Mass workouts, within which you might do ‘monster sets’ of lifts.

What’s this paper about?

Throughout most of history to be termed a ‘monster’ has been an insult, and monstrosity was something that was to be avoided. When we are faced with a community of people who aim to turn themselves into monsters, and revel in their monstrosity, it begs the question – why has monstrosity become desirable and sought after?

In order to work this out I will go through some of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) definitions of the term ‘monster’, and discuss how they relate to bodybuilding.

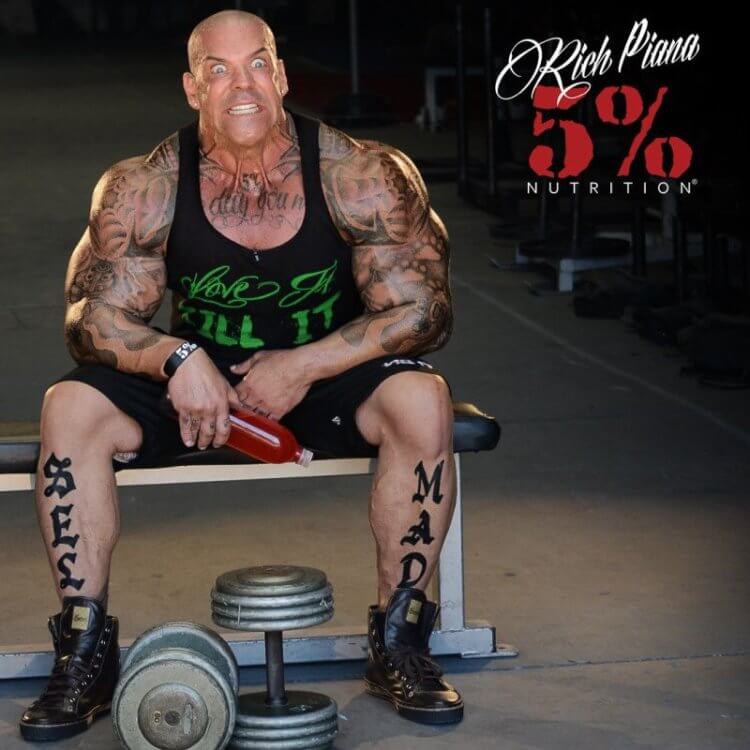

I will also focus on three case studies of high-profile bodybuilders who self-identify as ‘monsters’ or ‘freaks’: Rich Piana (controversial YouTube bodybuilder), Gregg Valentino (star of ‘The man whose arms exploded’) and Dave Crosland (star of ‘Under Construction’ 1 & 2). While bodybuilding is full of monsters and freaks, these are individuals who are on the fringes of acceptability in bodybuilding. They are the ‘freaks’ freaks’. They help us to understand how in a world of monsters, there are still limits of acceptability.

Finally, I will ask how bodybuilding monsters make sense in contemporary society.

Huge size

A creature of huge size (OED definition 4).

Bodybuilders have not always been monstrous. In fact, in 1901 the natural history branch of the British Museum in London produced a statue of ‘the perfect type of the European man’: a life-size model of Eugen Sandow, strongman, vaudeville performer and ‘father of modern bodybuilding’, whose physical features were widely considered the prototype of the beautiful human body (Conrad 2021).

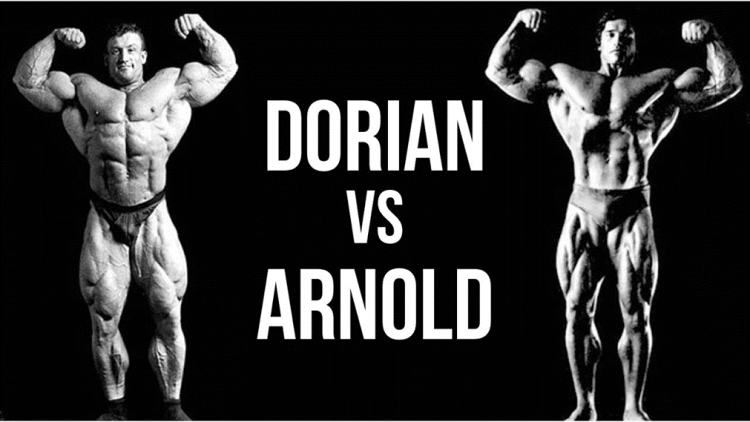

In the mid-20th century major bodybuilding competitions such as Mr Universe (now the World Amateur Bodybuilding Championships) and Mr Olympia (1947 and 1965 respectively) began, and it was also at this time that bodybuilding entered its ‘golden age’ (variously reported as starting around the 1950s or 60s, and ending in the 1970s or 80s). Golden age bodybuilders were known for their beautiful, aesthetic and flowing physiques. The most famous bodybuilder of this time was Arnold Schwarzenegger who competed at a weight of between 102-107kg at 188cm height and approximately 8% body fat.

It was from the mid-1980s, and particularly the 1990s, that bodybuilding first became monstrous. This was the beginning of the era of the ‘mass monster’. The first of these mass monsters is generally considered to be Dorian Yates (although some debate this point), who competed from 1980-1997, winning six consecutive Olympia titles from 1992 to 1997. Yates graced the Olympia stage heavier (approximately 118kg at a height of 178cm) and in better condition (body fat reportedly as low as 3%) than any of his predecessors. Indeed, he was the first to be of such low body fat that you could see his muscle fibres (a look that is now dubbed ‘grainy’), and the lack of fat on the soles of his feet allegedly caused him pain when walking.

The shift in bodies from golden age beauty, to mass monster, is generally attributed to changes in the enhancement drugs used. Golden age bodybuilders built their bodies through the use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) alone, whereas the mass monsters are said to have created their massive musculature through the use of insulin and human growth hormone, in addition to AAS. The mass monsters, and the drugs that spawned them, are claimed by some to have ‘ruined bodybuilding’, as size is seen to have become prioritised over aesthetics. Bodybuilding moved from a display of the ‘perfectible body’, to a display of the grotesque body, a shift that Richardson (2012) describes as the ‘enfreakment’ of bodybuilding. Bodybuilding moved from a celebration of beauty, to becoming a celebration of freakishness (Richardson 2012). From this time monstrosity became tied to bodybuilding, as a compliment, goal, and a central aspect of bodybuilding branding.

Deformation, malformation and unnaturalness

A malformed animal or plant; (Medicine) a fetus, neonate, or individual with a gross congenital malformation, usually of a degree incompatible with life (OED definition 3).

An ugly or deformed person, animal, or thing (OED definition 6).

There is, of course, an unnaturalness to the higher levels of bodybuilding. Hyper-muscularity can only be achieved by going beyond the limits of the natural body. In the early 2010s Rich Piana was sponsored by Mutant supplements, whose catch phrase is ‘leave humanity behind’. This sponsorship earned him the title ‘the supermutant’. He revelled in his unnaturalness, stating in a video that he had a biohazard symbol tattooed on his neck to refer to the amount of drugs he took because of his ‘whatever it takes’ attitude to bodybuilding.

To outsiders the ways that bodybuilders go beyond the limits of nature can be seen as deformation or malformation.

One of the most famous self-made freaks may be the late Lolo Ferrari, who had between 18-25 cosmetic surgery procedures (reports vary), mostly to enlarge her breasts, resulting in her ‘resembling an ancient fertility goddess or the graffiti project of a horny adolescent’ (Jones 2008:89). Ferrari’s breast implants were the biggest in the world, and are cited in the 1999 Guinness Book of World Records (Jones 2008). Ferrari was not a ‘freak of nature’. Rather the horror we feel when looking at her body is about her overconformity to cultural ideals: she went too far in her efforts to meet the cultural ideal of large breasts. She shows how frighteningly powerful culture can be (Richardson 2012). Richardson (2012) argues that people experience a similar thrill when they stare at the bodybuilding ‘freaks’ in the Mr. Olympia line-up.

The three case studies, Rich Piana, Gregg Valentino and Dave Crosland, not only horrify outsiders, but (to varying degrees) they horrify members of the bodybuilding community as well. One obvious reason for this is the lack of proportion and balance in their physiques. Gregg Valentino himself described his arms as ‘deformed’ and ‘ugly’ when they were this disproportionate.

Since he tore his pec Dave Crosland has:

“… just gone more the route of as big and as ugly as I can get [Under Construction].”

Unable to balance his physique he saw little point in trying to adhere to bodybuilding aesthetics. Not only did he give up on attempts to create an aesthetically balanced physique, but he focussed exclusively on size with little regard for condition – a choice that drew much criticism from some in the bodybuilding community.

An important reason that all three of these bodybuilders (Piana, Valentino and Crosland) are to varying extents considered freaks within the bodybuilding community of freaks, is that they are all accused of going beyond the limits of acceptable enhancement in bodybuilding. That is, they are all accused of administering compounds that are considered ‘unnatural’ or ‘fake’ according to bodybuilding norms: synthol and PMMA. Use of these substances can have its place in bodybuilding. They can be legitimately used to correct minor imperfections. But all three of these bodybuilders are accused of using these substances illegitimately to create large areas of mass.

Animality, ferocity and fright

Originally: a mythical creature which is part animal and part human, or combines elements of two or more animal forms, and is frequently of great size and ferocious appearance. Later, more generally: any imaginary creature that is large, ugly, and frightening (OED 1a).

For some bodybuilders animality, ferocity and their ability to frighten are important to their experience or image. For example, monstrosity and animality were key features in Rich Piana’s branding.

For Dave Crosland, animality and ferocity has not been about the image that he presented to others, as much as it has been a tool to achieve success in bodybuilding. Crosland’s training style was extremely intense (and this got him banned from numerous gyms). He described the transformation that occurred when he trained as follows.

“I used to go into [training] sessions visualising myself as something more than a human. For me it was a visualisation technique I used so that I would not allow preconceived limits of a human’s capabilities. Because I wasn’t a human at that point I was something else. And it sounds really corny when you talk about it, and it sounds almost like a joke. But when I trained I did approach my training as if there wasn’t a limit, as if I wasn’t limited by human boundaries. It was quite spiritual in a way. … There was a mental transformation. Obviously it wasn’t a physical transformation, but there was a mental transformation in the way I thought about the limitations when I was training, and I wasn’t just a person anymore, there was an animalistic core to it. There are certain shots if you find them [in my films], and you can see it in my eyes. You can genuinely see I am no longer in that room. … [I would] transcend myself into some form of animal. I would literally snarl and snort when I was training. And it wasn’t put on. … I would do that if I trained on my own. … The best way I can describe it is look at the Viking Berserkers, because they believed that they were possessed by an animal spirit that aided them in battle. … they fought with the ferocity of the animal they believed to be, or believed that they transcended into being, because that was more capable than they were. And it was a similar sort of thing in that if you mentally transform yourself into a creature or an animal or a machine then you are capable of much more than you would be as a person. Mentally it removes the limitations that you already have in your brain from your childhood, and from parenting, and from school, and everything else you have experienced up until that point that says you can’t do this, you can’t do that, because you aren’t that person you’re something else now [personal communication].”

Enthusiasm, success and perfection

Monster of perfection, indicating an astonishing or unnatural degree of excellence (OED 1b).

Something extraordinary or unnatural; an amazing event or occurrence; a prodigy, a marvel. (OED 2).

Originally U.S. An extraordinarily good or remarkably successful person or thing (OED 7).

But perhaps the most relevant definition of monstrosity to bodybuilding is the most recent definition, that which defines monstrosity as success. Bodybuilding started as perfection of the human body (Eugen Sandow), and to many perfection continues to be the aim, even if it means going beyond the limits of what most would term aesthetically pleasing. A bodybuilder’s body is a testament to their dedication and success, to their excellence in training, diet and enhancement drug use.

I think to be called a ‘monster’ is the ultimate compliment in bodybuilding, not just because it signifies great size, but because it signifies recognition of the effort it takes to create that size. It is a term of admiration and respect. It indicates an acknowledgement that the individual is deserving of all the benefits hyper-muscularity can bring. They are something to aspire to: they are truly monstrous.

‘I remember being 6 years old and my mom taking me to Gold’s [Gym] Sunrise, and I was too young to really think about working out. And I remember that one day everyone was like ‘who’s that guy?’, ‘who’s the guy over there?’, ‘who’s that guy?’, and he was wearing a sweatshirt and sweatpants, and it was Bill [Cambra]. And people were like ‘who is that guy? He’s a monster’, and the word got out that he was opening a gym down the street, it was Body and Power … I remember being at Body and Power 7, 8, 9 years old, you know, playing with my little He-man dolls, and one day I looked up and I’m like, wait a minute, there’s actually real He-men walking around the gym. And so then I started really analysing and watching everybody and watching the guys, and I noticed that the bigger individuals everyone looked up to them and the girls talked to them, and Bill had the sportscar. All this as a little kid, I would take this in, and I don’t know if I was destined or if I was pretty much screwed, because that’s where I was going to go, there was no way in the world that I wasn’t going to be a bodybuilder after seeing all this .”

How does bodybuilding monstrosity fit into its context?

Perhaps the most interesting thing to ponder about bodybuilding monstrosity is what it says about our culture. Monsters are always bound to specific sociocultural contexts, and they signify the issues that matter most to the people they ‘haunt’ (Musharbash and Presterudstuen 2014:12). Thus, monsters provide a window on the society in which they occur. What do bodybuilding monsters tell us about our society?

The most obvious thing they signify is our society’s increased emphasis on bodily control and discipline: the idea that the body is a project. Bodybuilders (like Lolo Ferrari) show us what happens when these ideas are taken to their extreme, or their logical conclusion. They show us what happens when every single aspect of exercise, diet and enhancement drug use, is tightly controlled and systematised.

Bodybuilders also reflect changes in our comic book superheroes. The golden (1938-1956) and silver ages (1956-c.1970) of comics overlap with the golden age of bodybuilding (approximately 1950s to 1970s). Golden age comic book superhero, Captain America (1941), originated as a sickly, frail, army reject, but then an experimental ‘super-soldier serum’ turns him into a near perfect human-being with unparalleled strength, agility, stamina, and intelligence. The parallels with the synthesis of testosterone (1935) and its eventual use by athletes (prior to the 1954 Olympics) and bodybuilders (c. 1960s), giving them super-human advantages over others, is obvious.

During the silver age of comics, superheroes became the monstrous progeny of the age of the atomic and genetic science. With mutated bodies and bizarre abilities (e.g. Spiderman, the Incredible Hulk, The Fantastic Four) these modern superheroes were an embodiment of the synthesis of nature with the technologies of industrial society (Fawaz 2016:6). This is when mutation became celebrated as advancement, heralding an era that eventually spawned the ‘super-mutant’, Rich Piana.

As leading monster theorist, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (1996:6) stated, monsters appear at times of cultural crisis. So, what crises could bodybuilding monsters be a response to?

It has long been suggested that bodybuilding is a response to a crisis in masculinity brought about by changing gender roles (Pope, Philips and Olivardia 2000). Maybe there is something to this theory given that some bodybuilders aim to get ‘dick skin’ shredded, and may take being told they look like a penis as a compliment: ‘Oh Sam, you looked like a human fucking penis! Veins were poppin’ every which way’ (Fussell 1991:232).

But bodybuilding may also be a response to another crisis: the obesity epidemic. Bodybuilding first arose at the same time as Western societies turned against fat: the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Stearns 1997). Consumer society where we are taught to consume, consume, consume, but to exercise restraint when it came to food, has always been a bit of a contradiction. What bodybuilding does is it allows individuals to consume massive amounts of food but to potentially gain little, or even lose, fat. Hence no more contradiction between consumer culture and our culture of the body. Bodybuilding allows us to be virtuous with food but also consume massive amounts: to exercise control, but also to be gluttonous.

I hope my musings have convinced you that the monsters of bodybuilding are not just big. They are also monsters because of their unnaturalness, their animality, and because they are bloody perfect at reflecting and solving the issues of contemporary society.

References cited

Conrad, S. 2021. Globalizing the Beautiful Body: Eugen Sandow, Bodybuilding, and the Ideal of Muscular Manliness at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Journal of World History, 32, 95-125.

Cohen, J. J. 1996. Monster theory: Reading culture, Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Fawaz, R. 2016. The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics, New York: New York University Press.

Fussell, S. 1991. Muscle: Confessions of an unlikely bodybuilder, London: Cardinal.

Jones, M. 2008. Makeover Culture’s Dark Side: Breasts, Death and Lolo Ferrari. Body & Society, 14, 89-104.

Musharbash, Y. & Presterudstuen, G. 2014. Monster Anthropology in Australasia and Beyond, New York, Palgrave Macmillan US.

Pope, H. G., Phillips, K. A. & Olivardia, R. 2000. The Adonis complex: How to Identify, Treat and Prevent Body Obsession in Men and Boys, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Richardson, N. 2012. Strategies of Enfreakment: Representations of Contemporary Bodybuilding. In: Locks, A. & Richardson, N. (eds.) Critical Readings in Bodybuilding. New York: Routledge. pp191-208.

Stearns, P. N. 1997. Fat history: Bodies and beauty in the modern West, New York: New York University Press.

About the author

Mair Underwood is an anthropologist who explores body cultures. She has been living in online bodybuilding communities for the last 6 years (she has even been inspired to start lifting). Through forums and social media she has learnt about bodybuilding culture. She has been particularly focussed on enhancement drug use, and she works to increase understanding of, and support for, people who use enhancement drugs.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.