When anabolic steroids were first criminalized in 1990, they had to be legislatively placed into the Controlled Substance Act. At that time, unlike traditional street drugs, anabolic steroids were not widely available, and there were three primary sources: a doctor, a Mexican pharmacy, or the big guy at the gym (who had a connection with one of the first two sources). Congress debated the issue for years, through multiple sessions, at first trying to schedule just the most common anabolic steroid, then composing a list of the twenty-seven and adding the whole category to the Controlled Substance Act. A unique sentencing strategy was implemented, and safeguards were put in place to prevent casual users from being treated like major dealers. But as years passed, and new legislation was added, steroids were increasingly treated like conventional narcotics until no practical distinction could be made between them.

Steroids are not like other drugs. Well, they’re not like other controlled substances. The Controlled Substance Act (CSA) was specifically designed to deal with mind-altering substances, various chemicals that get the user high. In 1990, Congress added anabolic steroids to the CSA legislatively (meaning they said “these drugs don’t belong here, but we can write a separate law ”). This was done through a standalone piece of legislation called the “Anabolic Steroid Control Act” (ASCA). But since literally all other controlled substances are packaged and sold differently than anabolic steroids, a different calculus was required to determine fair sentences for those convicted of steroid-related crimes. And again, owing to the fact that anabolic steroids were not incorporated in the CSA originally, neither were they accounted for under the Sentence Reform Act. The original guidelines under which anabolic steroid offenses were sentenced were founded in a modicum of discernible logic. If we accept the premise that steroids are a category of drugs that ought to be criminalized, we can speculate on the reasoning behind the original sentencing guidelines. But since then, there have been two major legislative modifications to federal steroid laws, and both were accompanied by significant changes in how they’re sentenced. The logic seen with original sentences has been discarded and what remains is a punishment that no longer fits the crime.

Currently, distribution of anabolic steroids carries a ten-year maximum sentence. A conspiracy to do the same thing carries a fifteen-year maximum sentence. But the simple possession of anabolic steroids (first offense) is a punishable by a maximum of 1 year in prison. Numerous details can factor into a steroid sentence, either tacking on more time, or taking it off. But I would argue that steroids are unlike drugs with comparable sentences and further that the calculus used to determine possession – or sometimes possession versus distribution quantities – is flawed.

Following the 1990 Anabolic Steroid Control Act, a bottle or vial was considered a single “unit” for the purpose of prosecution and sentencing. They were also limited to placement in Schedule III. This means that a procedure is undertaken to determine whether a given compound meets the legal definition of anabolic steroid. If the compound meets the criteria, it may be placed into Schedule III and may not be placed in any other schedule (there are five). The scheduling agency (the Drug Enforcement Administration) has no control over which schedule is appropriate if they conclude that a compound meets the definition of anabolic steroid. This mandate is unique to anabolic steroids– meaning apart from anabolic steroids, considerable scheduling latitude is permitted.

For example, opioids are all over the map — tramadol is found in Schedule IV, codeine (dosed below 90 milligrams) in Schedule III, Oxycodone is Schedule II, and Butyryl Fentanyl is in Schedule I, yet all are broadly defined as opioids. Codeine (for some reason) appears in multiple schedules based on dose per serving; there is no such proviso for anabolic steroids regardless of dose. Cathine is found in Schedule IV while Cathinone is in Schedule I, although both chemicals are found in the same plant (Catha edulis). Amphetamine is found in Schedule II, while some chemically related derivatives (3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine, or Ecstasy) are in Schedule I, despite the United States Code designation of amphetamine in Schedule III. In addition, because of the Analogue Act (*Controlled Substance Analogue Enforcement Act), an analogue of any drug in Schedule I or II may be charged as a Schedule I drug without appearing by name in the CSA. Steroids, as they are in Schedule III, are not ensnared by the Analogue Act.

Placement in Schedule III matters because as the scheduling designation decreases, the penalties increase. This means Schedule I drugs carry the harshest sentencing guidelines while Schedule V drugs have the most lenient. Besides scheduling designation, co-important factor in most drug sentences is the quantity, but not the quality (concentration in mgs/cc) involved. Think about this for a second (more if you’re particularly cerebral). If a cocaine dealer were arrested in possession of an equal amount of cocaine and a separate quantity of an inert cutting agent (some other white powder, intended for use in diluting the cocaine prior to selling), the dealer (if found guilty) would be sentenced according to the amount of cocaine involved. But if the arrest occurs a second after the dealer has mixed the cutting agent with the cocaine, now the dealer will be charged with a quantity that includes both the active ingredient and the cutting agent (twice as much, in this hypothetical). The cutting agent (without ever being added to the cocaine) could be introduced as evidence with the hope that the jury infers intent to distribute the cocaine (nobody cuts their own stash). The quantity of drug remains constant in both hypothetical examples but sentencing guidelines for the second instance is considerably longer (although note that levamisole, a cutting agent that may produce the “fish scale” look of some cocaine, serves to enhance the effects).

Sometimes Congress specifically makes an exception for the actual amount of drug to determine the sentence — without adding the carrier. PCP and methamphetamine are subject to a mandatory minimum sentence based on either on the weight of the mixture, or on lower weights of the pure drugs. But with anabolic steroids, the total amount (milligrams) of drug is almost irrelevant to the sentence. This is especially ridiculous when you consider that nobody buys a weekend’s worth of anabolic steroids. And it’s even more ridiculous when you consider the fact that a “unit,” unattached to any quantifiable metric, is a completely arbitrary way to measure any drug.

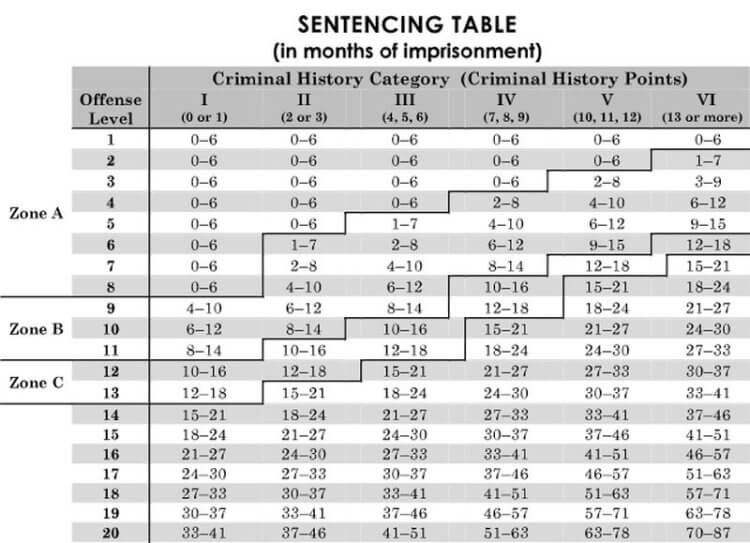

Contrast a single dose of an anabolic steroid with a single dose (line of cocaine, blotter of LSD, etc.) of a recreational drug and the disparity is obvious. Although federal sentencing guidelines currently measure all Schedule III substances in units, the guidelines did not measure Schedule III substances in units when Congress passed the Anabolic Steroid Control Act (ASCA). Following the passage of ASCA, one “unit” of anabolic steroids was initially defined as 50 pills (oral) or 10cc (injectable). In fact, the first Schedule III substance to be measured in units was anabolic steroids. This was the unit formula, for which the working U.S. Sentencing Commission Drug Working Group claimed the “calculation is based on common dosages of frequently used steroids.” I’ve never known an experienced steroid user to speak about anabolic steroids in terms of how many units they’re taking. The formula for determining a unit is: 1 unit = 1×10 cc vial or 50 pills. But a “cc” is a cubic centimeter, in which one can have a single milligram of anabolic steroid or (in the case of Boldenone Undeclynate, or Equipoise) concentrated to nearly a thousand milligrams (the extremely long ester attached to the parent hormone makes the raw form of the steroid a very thick liquid, as opposed to powder, the more common form of raw steroid hormone). Once you know how many units of anabolic steroids are involved, you can figure out your offense level and that (plus your criminal history) gets plugged into the federal sentencing table (along with some other factors, but you get the idea).

As the quantity of steroids increases, so does the offense level attached to the crime. We can project some degree of logic into this structure if we recall that when the “unit” was first codified into sentencing guidelines, a typical 10cc vial of testosterone contained 2,000 milligrams of testosterone and 50 oxymetholone or stanozolol (Anadrol or Winstrol) pills totaled 2,500 milligrams. Basically, around two grams of steroid was a unit. And in 1990 before the rise of Ttokkyo Labs, International Pharmaceuticals, and British Dragon, super-high-dose anabolic steroids were not available, and most doses were standardized. Cycles were also more reasonable, and with these guidelines, there were safeguards in place to assure the recreational steroid user would not be serving a drug kingpin sentence.

The unit formula was presumably designed to account for the fact that steroids impart an effect that manifests over the course of weeks and months, rather than immediately (as seen with recreational drugs). Steroid users often plan and cycle their use, and frequently even plan a course of drugs to be used after the cycle (post-cycle therapy). A casual user doing two cycles per year (assume a winter bulking cycle and a summer cutting cycle), could be buying their stash all at once, or buying more than they need (just in case their sources dry up). This means, from a consumer perspective, the average non-dealer steroid user is going to be caught with weeks (*if not months) worth of drugs, and this often translates to the jury to concluding that a user is in fact a dealer.

Apparently, the unit formula was based on the conclusion that it’s unreasonable to quantify a unit of steroids as an amount that could not be used in the same manner as a unit of recreational drugs. A single pill or ampule of anabolic steroid would produce no quantifiable result in the user; a 10cc vial or 50 pills is another matter entirely. This means steroid users are often arrested with a significant quantity. Hence, in most steroid prosecutions, the end user is likely to be found in possession of a drugs meant to be utilized over the course of weeks or months (a cycle). Multiple 10cc vials and hundreds of pills could reasonably be expected to comprise a single cycle for a single user. Consider the fact the most popular steroid of the time, Dianabol or methandrostenolone, was only available in 5mg/tablet, and Anavar or oxandrolone, was half of that (yes, a 2.5mg tablet). A professional bodybuilder in the precontest phase would likely be found in possession of enough drugs for multiple users, over multiple cycles and even years. Craig Titus, the IFBB professional bodybuilder, after being arrested in possession of a sizeable amount of anabolic steroids, famously stated “I don’t deal steroids, I horde them!”

For these reasons, we can assume the U.S. Sentencing Commission, following the Anabolic Steroid Control Act, accounted for this by creating a zone whereby the casual steroid user, caught in possession of a full cycle, would be unlikely to face distribution level penalties. This unit designation remained in place through the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004 (ASCA 2004), which directed the U.S. Sentencing Commission to revisit the sentencing guidelines.

After enactment of ASCA 2004, and the Supreme Court’s 2005 holding in United States v. Booker, the U.S. Sentencing Commission published in the Federal Register a Notice of Proposed Priorities and Request for Public Comment. On April 12th, 2005, the Sentencing Commission heard testimony as to why steroid sentencing guidelines should not be increased. Following the notice and subsequent testimony, on March 27th of 2006, the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC) published to the Federal Register a notice of emergency amendments to the sentencing guidelines. The notice provided that injectable and oral steroid “units” would now be adjusted upwards, resulting in a 1:1 ratio to other Schedule III drugs. But as the criminalization of anabolic steroids was always a square peg in a round hole, making them otherwise equivalent to similarly scheduled drugs only emphasized and exacerbated the sentencing problems.

The new guidelines established that one “unit” of an oral steroid was now quantified as a single pill (whether tablet or capsule), while one “unit” of a liquid steroid was to be 0.5cc. This increase: 50-fold and 20-fold) seems to imply that injectable anabolic steroids are “worse” than oral steroids, which is simply unfounded. This is especially problematic when considering the market. Oral and injectable anabolic steroid pills are sold by pure dose, unlike recreational drugs, which are either sold by weight or presentation (the local marijuana dealer doesn’t sell by THC concentration and the local cocaine dealer doesn’t provide HPLC analysis for each eightball). Also note that ASCA 2004 was primarily focused on steroid precursors or “prohormones” because…umm…homeruns or something.

Other forms of presentation (topical, intranasal, buccal, powder, etc.) were to be estimated based on a “unit” weighing 25 milligrams. These new guidelines, first adopted as an emergency amendment, was later adopted permanently. The rule generates internal inconsistency that defies remedy. What about liquid steroids that are consumed orally? What about stanozolol, which in liquid form can be injected or swallowed? Why does a 50mg pill carry the same penalties as a 5mg pill? What about pills that contain liquid (testosterone undecanoate, or Andriol, for example). What about someone who homebrews their own steroids — making 2 grams of raw hormone powder (enough for a 200mg/ml x 10ml vial, or 20 units) now punishable as a unit quantity 4x higher (2 grams = 2,000 mgs, divided by the 25mg unit dose).

Don’t think too hard about these questions because there’s no logical answer.

Some of these problems may be resolved (or resolvable) through the discretion provided to the sentencing court. In. Kimbrough v. United States, a 2007 case dealing with the discrepancy between crack cocaine and powder cocaine sentences, the Supreme Court held that district judges may sentence defendants to lesser terms than outlined in the guidelines. At the time of that holding, crack and powder cocaine offenses had a 100:1 ratio, but the potential gap created by the 2006 emergency amendment to steroid sentencing guidelines is far greater than the crack/cocaine disparity. If we consider the hypothetical situation of one steroid user caught with 10mls of raw Equipoise liquid (nearly 10,000 milligrams, or 20 “units”), versus another one caught with a 50ml jug with a 50mg concentration (2,500 milligrams but 100 “units”) it seems obvious that the second user should be facing less potential prison time). A judge may factor these considerations into crafting an appropriate sentence, but this is certainly not required.

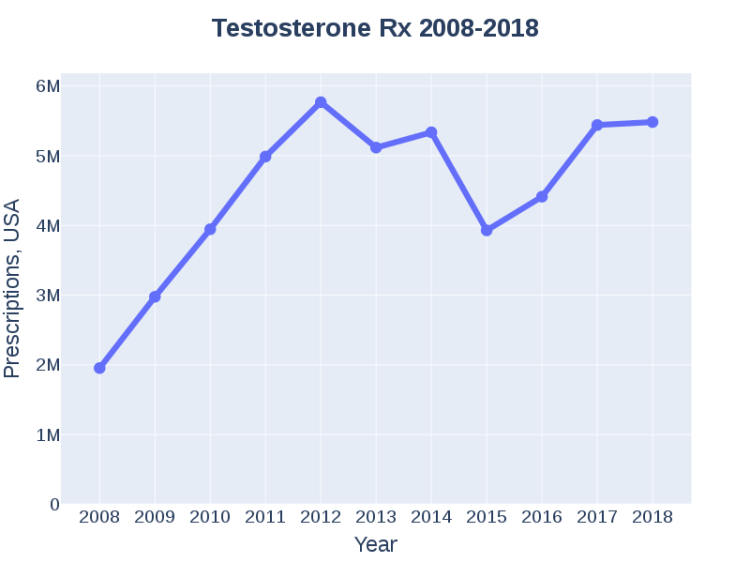

The first incarnation of the Designer Anabolic Steroid Control Act (DASCA) was proposed in 2009 as part of the Food Safety Modernization Act. This was at a point where testosterone prescriptions were on an upswing and “Low T” (low testosterone) advertising campaigns had begun to take hold. In 2014, the year DASCA was finally signed into law regulators had begun to raise public safety concerns linking it to heart disease.

Both the 2010 and 2012 rewrites of DASCA provided that the U.S. Sentencing Commission revisit the anabolic steroid sentencing to unify standards for the various presentations (lozenges, patches, and the like) into an equivalent dose as it relates to other (liquid and pill) forms “whose dosage can be readily ascertained.” Protip: all steroid doses can be readily ascertained, and its quantifiable by milligrams, not milliliters.

Protip: all steroid doses can be readily ascertained, and its quantifiable by milligrams, not milliliters.

But again, the new unit designations instituted by the Sentencing Commission fail to be internally consistent. This is not excusable by the mere fact that exception used to incorporate anabolic steroids into the CSA accounts for other scheduling dissimilarities. Again, anabolic steroids cannot reasonably correspond to any sentence that equivocates them with the psychotropic drugs found in Schedule III. Nobody has ever been arrested for driving under the influence of anabolic steroids, most users display few behavioral effects, and severe steroid induced criminality is uncommon.

The 2014 House version of DASCA, the one that was enacted, removed the sentencing language, and included a new definition of “unit” for retail sales, and (vaguely) conditions wherein definition may be relevant (e.g., failing to use the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry — IUPAC — Nomenclature for steroid ingredients, unless the product is otherwise compliant with the applicable FDA Regulations for labeling). But as steroids (apart from DHEA) are not acceptable dietary ingredients, I see no way for that condition to be satisfied. In addition, using the IUPAC Nomenclature instead of common names could potentially violate existing guidelines for labeling dietary supplements.

The act also addresses retail distribution and sales as a “case of a distribution, dispensing, or possession with intent to distribute or dispense in violation of…this section at the retail level, up to $1000 per violation. For purposes of this paragraph, the term at the retail level refers to products sold, or held for sale, directly to the consumer for personal use. Each package, container or other separate unit containing an anabolic steroid that is distributed, dispensed, or possessed with intent to distribute or dispense at the retail level in violation…shall be considered a separate violation. “

The new “retail” clause refers to each package or container (presumably a bottle), making each a separate violation up to $1,000 per unit. If I’m interpreting this correctly, it may be an attempt to address a retail store or online vendor selling third-party “prohormones” (typically anabolic steroids that are not listed anywhere on the CSA) as dietary supplements, but otherwise uninvolved in the manufacture of the product. It’s not clear to me whether the intent is to make this fine a standalone penalty for the retail distributor or in addition to the other criminal penalties to which the retailer may be exposed. But as the term “retailer” is used distinctly in this part of the statute, I can only assume that it’s meant to create a division between brands and manufacturers producing the steroid versus those entities who are just selling it.

This is alluded to elsewhere, where a category of entities distinct from retailers provides for the case of a violation by an importer, exporter, manufacturer, or distributor can result in up to $500,000 per violation (a violation is defined as each instance of importation, exportation, manufacturing, distribution, or possession with intent to manufacture or distribute). This appears to be a distinct penalty from those retailing the products, although it’s easy to see that most brands are also retailing their own products in a direct to consumer fashion (thereby making the two sections more likely additive as opposed to mutually exclusive).

It’s important to remember that until now we have been dealing exclusively with steroid legislation handed down by Congress, and federal sentencing guidelines. Many (some claim most) steroid cases are prosecuted on the state level. This may be true, although the bigger cases will almost certainly remain the province of federal prosecutors. Although as a practical matter, as the most common source for steroids has been, and will continue to be, the internet, it’s no stretch of the imagination to see that the use of interstate communications and federal mail services will place these crimes within the ambit of federal law as well. And frankly, most of the relevant state legislation closely mirrors the federal code (with some exceptions).

But regardless of whether we are discussing federal or state court, sentences handed down to those in possession of anabolic steroids are flawed from the outset, by the mere premise that they are in any way equivalent to the other drugs listed under the Controlled Substances Act. I would also argue that because of the way units are calculated, sentences given to traffickers and dealers are similarly misguided. Steroids do not belong in Schedule III or any other schedule, as they fail to meet the primary and secondary criteria. Accordingly, imprisonment, or even the threat of imprisonment, for their mere possession is always going to be excessive. But setting their dubious status as controlled substances aside, it is wholly inexcusable that after they were criminalized, and as their medical utility has becomes more accepted and prescriptions more commonplace, sentencing guidelines have become more severe. This is reprehensible and in direct conflict with societal demands for sentence reform.

End Notes:

As usual I have some suggestions for further reading.

This article examines the contextual factors of 63 anabolic–androgenic steroid (AAS) cases involving 184 defendants, nationwide:

Denham, B. E. (2019). Anabolic Steroid Cases in United States District Courts (2013–2017): Defendant Characteristics, Geographical Dispersion, and Substance Origins. Contemporary Drug Problems, 46(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450918800823

This article is a great primer on the trend of steroid users who homebrew their own drugs:

Brennan, Rebekah & Wells, John & Hout, Marie-Claire. (2017). “Raw juicing” – an online study of the home manufacture of anabolic androgenic steroids (AAS) for injection in contemporary performance and image enhancement (PIED) culture. Performance Enhancement & Health. 10.1016/j.peh.2017.11.001.

This review/study is on behavior and is the source material for my claim that most users display few behavioral effects, and severe steroid induced criminality is uncommon:

Pope, H. G., Jr, Kanayama, G., Hudson, J. I., & Kaufman, M. J. (2021). Review Article: Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids, Violence, and Crime: Two Cases and Literature Review. The American journal on addictions, 30(5), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13157

This article covers testosterone use and prescription trends:

Carter, I.V., Callegari, M.J., Jella, T.K. et al. Trends in testosterone prescription amongst medical specialties: a 5-year CMS data analysis. Int J Impot Res (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-021-00497-6

About the author

Anthony Roberts is an expert in the field of performance and image enhancing drugs. He has authored books ranging from the pharmacology of anabolic steroids and growth hormone to their illicit use and trafficking. His writing can be found in magazines such as Muscle Evolution, Muscle & Fitness, Human Enhancement Drugs, Muscle Insider, and Muscular Development.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.