Thyroid hormones are hormones that are secreted by the thyroid. The thyroid is an endocrine gland in the front of your neck that’s located directly below the larynx (Adam’s apple), weighing close to 20 g. The two principal thyroid hormones that it secretes are triiodothryonine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). The latter functions mostly as a prohormone as most of its effects rely on conversion into T3. This T4-to-T3 conversion, also called outer ring deiodination, takes place mainly outside of the thyroid in peripheral tissues. Collectively this leads to a daily production of about 88 mcg (113 nmol) T4 and 28 mcg (43 nmol) T3 [2]. About one fifth of the T3 is derived from the thyroid, whereas the other four fifths is produced by extrathyroidal T4-to-T3 conversion [3].

Just as with anabolic steroids, thyroid hormones are transported in the bloodstream by carrier proteins. The majority is bound to thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), with the remainder bound to transthyretin, albumin and some lipoproteins. Collectively they bind over 99 % of thyroid hormones in the circulation. It’s thought that the unbound fraction is available for tissues for uptake and is responsible for its effects [4]. Though there are some caveats to the evidence for this, I’m not gonna get into a free hormone hypothesis discussion here (other than mentioning that in its strict form it’s wrong, but free thyroid hormone measurements are useful nevertheless).

Once it reaches the peripheral tissues, and crosses the plasma membrane of a cell, it’s time for some action. In the case of T4, it first needs to be converted into T3 as mentioned before, as T4 can be viewed as a prohormone. This conversion takes place inside the cell, either close to the plasma membrane (after which it quickly equilibrates with the blood plasma), or close to the cell nucleus—the site of action [5].T3, on the other hand, can directly continue its journey by getting into the cell nucleus. The cell nucleus is the organelle of the cell where gene transcription takes place. Just as anabolic steroids do, thyroid hormones primarily exert their effects through modulation of gene transcription. They do so by binding to thyroid hormone receptors which are mainly located inside the cell nucleus, bound to the DNA.

Thyroid hormones affect a vast array of tissues and have a plethora of effects, but for this article I’ll be focusing on its effect on energy metabolism and (skeletal muscle) protein turnover. Most likely the two most interesting for the people reading this in regard to its efficacy.

Effect on energy metabolism

When someone lacks sufficient thyroid hormones, this person is said to have hypothyroidism. One of the characteristics of hypothyroidism is weight gain. Conversely, when someone has too many thyroid hormones, this person is said to have hyperthyroidism. One of the characteristics of this is weight loss. These changes in weight are, likely, the result of changes in basal metabolic rate. It’s well-known that thyroid hormones increase energy expenditure.

A few mechanisms have been proposed on how thyroid hormones achieve this. In this article I’ll cover the three most interesting ones (or perhaps simply the ones you encounter the most in the scientific literature). The first two mechanisms resolve around the energy that’s required to maintain ion gradients within the cell. For example, cells maintain a low intracellular concentration of sodium and a high intracellular concentration of potassium relative to the outside of the cell. Maintaining this is done by pumps embedded in the plasma membrane, and these pumps require energy to function. They pump sodium ions out of the cell, and pump potassium ions into the cell. These pumps are known as Na+/K+-ATPases, or simply, sodium-potassium pumps. The energy these pumps require to function is derived from the energy-carrier molecule adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is used by many cellular processes to fuel its energy needs, and the energy that’s contained in these molecules is derived from the energy-rich macronutrients we eat: carbohydrates, fatty acids and protein (amino acids). In a previous article of mine about 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) I describe the primary way how cells produce these ATP molecules through a process called oxidative phosphorylation. The interested reader is referred to this article. This article will become more relevant further down as well, as one of the ways of how thyroid hormones might increase energy expenditure is similar to how DNP achieves this—through ‘sabotaging’ oxidative phosphorylation.

Anyway, I’m drifting off a bit. Back to the sodium-potassium pumps. Some evidence suggests that thyroid hormones increase the permeability of the plasma membrane to sodium and potassium ions [7]. This means as much as more of these ions will leak down their concentration gradient. So potassium ions will leak out of the cell, and sodium ions will leak into the cell. As a result, the sodium-potassium pumps need to pump a little harder to maintain the desired intracellular concentrations of these ions and this costs energy. Indeed, some literature even suggests that all mammalian tissues show an increase in sodium-potassium pump activity in response to T3 [8].

Something similar has been suggested with regard to calcium ions in muscle cells [9]. Muscle cells are quite special cells in many ways. One of them is that they contain an organelle called the sarcoplasmic reticulum. It’s a specialized form of the endoplasmic reticulum encountered in regular cells. One of the things that makes it special is that it functions as a storage site of calcium ions. These calcium ions play a pivotal role in muscle contraction, as unloading of these calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the rest of the cell leads to muscle contraction. Once contraction needs to stop, these ions are pumped back again into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This process, of course, also consumes energy. And here’s the kicker, thyroid hormones have been found to regulate the expression of these calcium pumps in animal models. Moreover, they increase the activity of a certain type of receptor in muscle tissue which stimulates the unloading of these ions into the cytosol [10]. So this is another thing that points into a potential increase in energy expenditure as a result of maintaining this calcium ion storage in the endoplasmic reticulum.

Finally, there’s good evidence that indicates that it ‘sabotages’ oxidative phosphorylation. I’ll briefly go over oxidative phosphorylation for those of you that haven’t read the DNP article that I was referring to above. Briefly, oxidative phosphorylation takes place in a cell organelle called the mitochondria. The macronutrients we eat get broken down further to smaller constituents and in this process energy is released in the form of electron pairs. A complex molecular play in the mitochondria between various molecules and protein complexes extracts the energy from these electron pairs by, essentially, using this energy to pump protons (H+) around. These protons are pumped outside the core of the mitochondria called the mitochondrial matrix and into the intermembrane space—the space between the inner and the outer mitochondrial membrane (as mitochondria have two membranes, one wrapping around the other). This creates a proton gradient, with a high proton concentration in the intermembrane space, and a relatively low concentration in the mitochondrial matrix. Just as water flowing down from high to low, from which we can extract energy with a water turbine, your cells can extract energy from these protons flowing down their concentration gradient by guiding this flow through an awesome protein machinery called ATP synthase. This is what fuels the synthesis of ATP.

Ok, so back to how thyroid hormones affect this: they increase the expression of uncoupling proteins [11, 12]. These are proteins embedded in the inner membrane of the mitochondria and they let protons leak down their concentration gradient. So protons will go from the intermembrane space to the mitochondrial matrix, without passing ATP synthase. Thus, the energy is released as heat rather than being turned into the production of ATP.

Pretty cool, huh?

Thyroid hormones affect protein turnover

I got inspired by a forum post to write this article. Someone was taking T3 to increase protein turnover during a bulk. Is that a good idea? No. While protein turnover increases, as there’s a concurrent rise of both protein synthesis as well as protein breakdown, the latter is exceeding the rate of synthesis. As such, net protein breakdown is taking place.

In one trial in which subjects received 150 mcg T3 daily for 7 days, protein breakdown increased a lot [13]. Nitrogen excretion (a proxy for protein breakdown) increased by 45 % and leucine oxidation increased by 74 %. A small increase of whole body protein synthesis was also found, but the magnitude was smaller than the increase in protein breakdown. A different study, employing 100 mcg T3 daily for 2 weeks, found similar results [14]. Fasted whole-body protein synthesis increased by 9 %, albeit not statistically significant, whereas whole-body protein breakdown and leucine oxidation did demonstrate a statistically significant increase of 12 and 24 %, respectively.

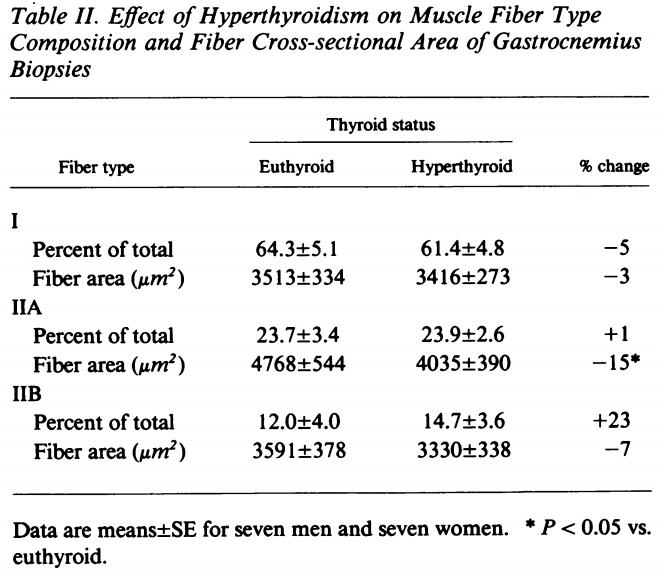

Perhaps more interestingly was that the researchers also took muscle biopsies from the gastrocnemius muscle. They measured a bunch of things, including the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the muscle fibers. The results were as follows:

This is quite drastic for a mere 2 weeks. (Also note the fiber type shift that’s induced by a hyperthyroid state.)

In another study, six participants received 2 mcg/kg bw T4 daily for 6 weeks, along with 1 mcg/kg bw daily T3 for the last 2 weeks [15]. This (the first 4 weeks) is a bit above a full thyroid hormone replacement dosage. And, indeed, TSH was suppressed from 1.8 to 0.3 mIU/L, and both T4 and T3 increased significantly. The subsequent addition of T3 made TSH levels undetectable and increased T3 levels even further. Muscle protein kinetics were not measured in this study. They did measure whole-body protein synthesis and breakdown in the postabsorptive state. The thyroid hormone supplementation led to an increase in both, but with a substantial higher increase in breakdown. It would be a reasonable assumption that this also reflects what is happening in muscle tissue.

Finally it’s also worthwhile to highlight another study of long duration, with a relatively low dosage compared to the other trials. Lovejoy et al. administered T3 for 2 months to a small group of men [16]. Dosing started with 75 mcg T3 daily, but was titrated downwards to 50 or 62.5 mcg daily when serum T3 levels exceeded 4.6 nmol/L. Which, indeed, was the case for 5 of the 7 men participating. Nitrogen balance was significantly decreased compared to baseline in the second and third week, but tended to return toward zero afterwards. This is suggestive of some protein-sparing mechanism kicking in after the initial few weeks. Additionally, they found a significant decrease in lean body mass (-1.5 kg) and fat mass (-2.7 kg) after 6 weeks. At week 9, lean body mass did not decrease further (-0.1 kg compared to week 6), whereas fat mass appeared to continue to decline (-0.6 kg), albeit this was not a statistically significant difference compared to week 6. They did not find any statistically significant differences in measures of protein turnover, but this was likely the result of the small sample size: a type 2 statistical error.

Could anabolic steroids negate these catabolic effects of thyroid hormones? Probably, to some degree, but there’s no clinical data about this. So all I would do here is to guess. It should be wondered whether the small increase in energy expenditure (few hundred kcal, ball park +10-15 % increase in resting metabolic rate) is worth the catabolic effects and potential adverse effects of usage of this class of drugs.

References

- Carlé, Allan, Anne Krejbjerg, and Peter Laurberg. “Epidemiology of nodular goitre. Influence of iodine intake.” Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism 28.4 (2014): 465-479.

- Nicoloff, John T., et al. “Simultaneous measurement of thyroxine and triiodothyronine peripheral turnover kinetics in man.” The Journal of clinical investigation 51.3 (1972): 473-483.

- Bianco, Antonio C., et al. “Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases.” Endocrine reviews 23.1 (2002): 38-89.

- Mendel, Carl M. “The free hormone hypothesis: a physiologically based mathematical model.” Endocrine reviews 10.3 (1989): 232-274.

- Gereben, Balázs, et al. “Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling.” Endocrine reviews 29.7 (2008): 898-938.

- Cheng, Sheue-Yann, Jack L. Leonard, and Paul J. Davis. “Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions.” Endocrine reviews 31.2 (2010): 139-170.

- Silva, J. Enrique. “Thermogenic mechanisms and their hormonal regulation.” Physiological reviews 86.2 (2006): 435-464.

- Ismail-Beigi, Faramarz. “Thyroid hormone regulation of Na, K-ATPase expression.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 4.5 (1993): 152-155.

- Everts, M. E. “Effects of thyroid hormones on contractility and cation transport in skeletal muscle.” Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 156.3 (1996): 325-333.

- Mullur, Rashmi, Yan-Yun Liu, and Gregory A. Brent. “Thyroid hormone regulation of metabolism.” Physiological reviews 94.2 (2014): 355-382.

- Barbe, Pierre, et al. “Triiodothyronine‐mediated upregulation of UCP2 and UCP3 mRNA expression in human skeletal muscle without coordinated induction of mitochondrial respiratory chain genes.” The FASEB Journal 15.1 (2001): 13-15.

- de Lange, Pieter, et al. “Uncoupling protein-3 is a molecular determinant for the regulation of resting metabolic rate by thyroid hormone.” Endocrinology 142.8 (2001): 3414-3420.

- Gelfand, Robert A., et al. “Catabolic effects of thyroid hormone excess: the contribution of adrenergic activity to hypermetabolism and protein breakdown.” Metabolism 36.6 (1987): 562-569.

- Martin, WH 3rd, et al. “Mechanisms of impaired exercise capacity in short duration experimental hyperthyroidism.” The Journal of clinical investigation 88.6 (1991): 2047-2053.

- Tauveron, I. G. O. R., et al. “Response of leucine metabolism to hyperinsulinemia under amino acid replacement in experimental hyperthyroidism.” American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 269.3 (1995): E499-E507.

- Lovejoy, Jennifer C., et al. “A paradigm of experimentally induced mild hyperthyroidism: effects on nitrogen balance, body composition, and energy expenditure in healthy young men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 82.3 (1997): 765-770.

About the author

Peter Bond is a scientific author with publications on anabolic steroids, the regulation of an important molecular pathway of muscle growth (mTORC1), and the dietary supplement phosphatidic acid. He is the author of several books in Dutch and English, including Book on Steroids and Bond's Dietary Supplements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.