In my previous article on male-pattern baldness, or androgenetic alopecia, I narrated how hair growth and this condition roughly work. In this article I’ll highlight some of the treatment modalities that can counteract the development of male-pattern baldness.

Given the pivotal role of androgens in development of this condition, it should come as no surprise that some treatment modalities have targeted this role. An FDA approved drug that works through this is (oral) Finasteride. This is a drug that inhibits the enzyme responsible for the conversion of testosterone into the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Another class of drugs, of which none is approved (yet), are the androgen receptor antagonists. These work by antagonizing the effects of DHT, and other androgens, at the receptor level (e.g. topilutamide).

Another FDA approved drug, and there are actually as of writing this only 2 approved, is topical minoxidil. The treatment of androgenetic alopecia with minoxidil isn’t one that surfaced as a result of advances in our understanding of the condition. It was actually used for another condition (albeit given orally), namely hypertension, and it was discovered by chance that it led to hair growth in these patients. Hence they started trying it as a treatment for androgenetic alopecia, and voila, it worked.

While not a drug, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has gained quite some traction in the past few years as a viable treatment option too. PRP is simply blood plasma with more platelets in it than regular blood plasma. These platelets contain a variety of growth factors and cytokines and it’s thought that these play an important role in stimulating hair growth. This PRP is then repeatedly injected into the affected areas with tiny needles.

Yet other treatment modalities center around the role that prostaglandins play in the development of male-pattern hair loss. Prostaglandins are lipid molecules that are derived from the fatty acid arachidonic acid. There are a whole bunch of them, and it’s thought that some of these promote androgenetic alopecia, whereas others inhibit its progression. As such, drugs have been developed that target enzymes responsible for the production of some of these prostaglandins.

Finally, a bunch of signaling pathways are involved in the development of androgenetic alopecia, of which the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is one of them. It’s a pathway that’s involved in a myriad of processes, but in this article I’ll just focus on its role in androgenetic alopecia. In brief, activation of this pathway by Wnt proteins leads to accumulation of stable β-catenin in the cell, which translocates to the nucleus and then upregulates Wnt target genes. These genes apparently play an important role in the hair follicle and hair cycle. As such, drugs that modulate this pathway have been developed.

In the following sections I will go into more detail into how the more conventional treatment modalities work, that is: oral finasteride and topical minoxidil. Additionally, I’ll cover the topical counterpart of finasteride and oral counterpart of minoxidil. In my next article I’ll focus on the more experimental treatments, that is, topical androgen receptor antagonists and prostaglandins, PRP therapy, and Wnt signaling modulators.

Oral 5a-reductase inhibitors (Finasteride/Dutasteride)

This class of drugs hook into the pivotal role androgens play in the condition. More specifically, they inhibit the conversion of testosterone into the more potent androgen DHT by 5α-reductase enzymes. There are three known 5α-reductase isozymes, aptly named type I, type II and type III. The drug Finasteride is potent at inhibiting type II and type III, but it’s relatively weak at inhibiting type I [1]. Dutasteride is potent at inhibiting type I and III, although it’s reported to be approximately four times less potent at inhibiting type II than finasteride in a study evaluating the potency for all three isozymes [1]. However, studies performed prior to the discovery of type III suggest that dutasteride is about 3-fold more potent than finasteride on type II [2]. It’s unclear what causes this discrepancy. Regardless, a study performed in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia demonstrated dutasteride to be superior to finasteride in terms of suppressing serum DHT [3]. Once-daily dosing for 24 weeks of 0.5 mg dutasteride, 5.0 mg dutasteride or 5.0 mg finasteride led to a serum DHT decrease of 94.7, 98.4 and 70.8 %, respectively.

The type III isozyme is ubiquitously expressed in high concentrations, including the skin [1]. Notably, type I is also expressed in the skin to an appreciable extent. As such, finasteride leads to incomplete suppression of 5α-reductase activity. As such, the hair follicles might still be exposed to significant DHT exposure as a result of local production of DHT. One study found scalp skin DHT levels to be decreased by 43 % after 28 days of 5 mg finasteride daily [4]. Another study found a decrease of 69 % after 42 days with the same dosage [5]. Yet another study measured scalp skin DHT levels after treatment with finasteride or dutasteride for 24 weeks [6]. It decreased by 41 % in the men receiving 5 mg finasteride daily, whereas it decreased by 51 % with 0.5 mg dutasteride daily and 79 % with 2.5 mg dutasteride daily. It’s unclear why one study found a relatively large decrease in scalp skin DHT levels of 69 %, whereas the other two found it to be 41-43 %. Nevertheless, since one of them made a head-to-head comparison, it’s clear that dutasteride leads to a stronger suppression of DHT in the scalp. Which is to be expected given it’s very strong potency in reducing serum DHT levels too compared to finasteride, which reflects what’s happening in the peripheral tissues collectively.

While treatment response can vary substantially, overall the response to treatment can be considered to be good. In a large double-blind randomized controlled study, an increase in hair growth was observed in 48 % of men treated with finasteride, whereas it was observed in only 7 % of men in those treated with placebo [7]. A 2014 network meta-analysis concluded that finasteride and dutasteride were similarly effective [8]. Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that some trials demonstrated (albeit a small) superiority of dutasteride over finasteride [6, 9]. The 2018 guidelines by the European Dermatology Forum also note that “oral 0.5 mg/day can be considered in case of ineffective previous treatment with 1 mg finasteride over 12 months as a second line treatment to improve or to prevent progression of AGA in male patients above 18 years with mild to moderate androgenetic alopecia” [10].

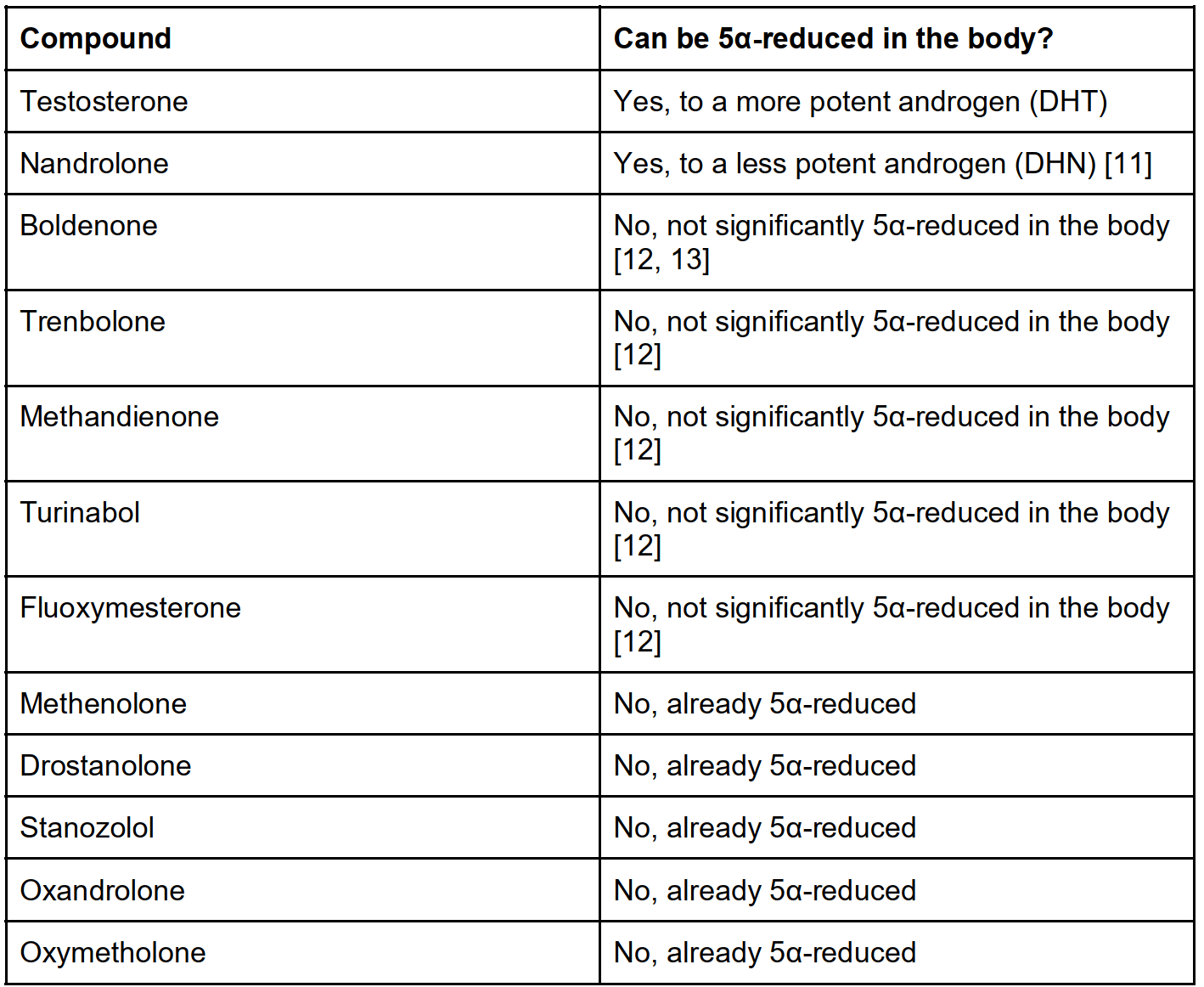

However, it’s important to highlight that all these studies are done in men with physiological testosterone levels. There’s a logical difference between this situation, and the situation in which an anabolic steroid user administers high doses of testosterone, often in conjunction with other anabolic steroids. First, it’s unclear how effective this treatment modality is with high doses of testosterone used alone. After all, despite the decrease in DHT, there will still be significant increased androgenic action resulting from the high levels of testosterone itself. Second, because it works through inhibiting 5α-reductase, it will, practically speaking, not work on other AAS than testosterone. After all, of the commonly used anabolic steroids, only testosterone is converted into a more potent androgen in the body to a significant degree. Moreover, concurrent use of a 5α-reductase inhibitor with nandrolone might make things worse. The reason for this is that, unlike testosterone, nandrolone is converted to a less potent androgen (dihydronandrolone) [11]. So whereas testosterone’s effect is amplified by 5α-reduction, it’s weakened in the case of nandrolone. It therefore stands to reason that this class of drugs is most effective in anabolic steroid cycles using relatively low doses of testosterone. It stands to reason that higher dosages, as well as stacking it with other anabolic steroid compounds, make this treatment modality exceedingly less effective.

Common anabolic steroids and their ability to be 5α-reduced in the body. Table taken from Book on Steroids.

Overall, 5α-inhibitors are well-tolerated [14]. Nevertheless, sexual dysfunction and psychiatric side effects have been reported. While no causal link had been established, anecdotal evidence of mood changes and small studies reporting depressive symptoms relating to finasteride use have led to depression being added as an adverse reaction to the product labeling of the drug in 2011 [14]. Either way, this does suggest this side effect is quite rare. Erectile dysfunction seems to be more common. A 2010 meta-analysis suggests that, compared to a placebo, 1 in 80 will experience erectile dysfunction as a result of finasteride use [15]. However, no significant difference compared to a placebo was found in decreased libido or ejaculation dysfunction. A 2013 Similarly, around 1 in 80 also can get gynecomastia from its use compared to placebo [16]. Side effects usually resolve after discontinuation of the compound, although they are suggested to persist in some cases. This is also called the post-finasteride syndrome and is described as a “constellation of sexual, physical, and psychological symptoms that develop during and/or after finasteride exposure and persist after drug discontinuation” [17]. Considerable debate exists in the literature about whether or not post-finasteride syndrome even exists [17, 18, 19]. One paper went as far as suggesting it may represent a delusional disorder, stating: “We present the first case of PFS [post-finasteride syndrome] in our 20-year prescription practice of oral finasteride for treatment of male pattern baldness, with circumstantial evidence that PFS may represent a delusional disorder of the somatic type, possibly on a background of a histrionic personality disorder, and with the potential of a mass psychogenic illness due to its media coverage.” [19] Regardless, while it’s obviously hard to get solid evidence for a causal link, the lack of sufficient data to establish this doesn’t mean it’s not real. As such, it seems prudent to support further research in order to paint a clearer picture of its causal link with finasteride use, incidence and pathophysiology, while also maintaining a cautionary stance and informing the public of this rare possible side effect.

Topical Finasteride

It appears pretty straightforward that the side effects from oral finasteride use result from its systemic exposure. As such, it’s very reasonable to try and formulate a topical version that targets the scalp specifically, minimizing its systemic exposure. And indeed, that’s what happened.

Already in 1997—the same year as oral finasteride received FDA approval for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia—the results of the first clinical trial evaluating the effects of a topical 0.005 % finasteride solution on androgenetic alopecia were published [20]. The small, 16-month placebo-controlled trial, saw a significant advantage of topical finasteride (twice 1 mL daily) compared to placebo. Interestingly, no patient experienced any local or systemic untoward effect. And no changes in serum total and free testosterone or dihydrotestosterone were observed; confirming its minimal systemic exposure. However, a later trial using a 0.25% topical solution by the pharmaceutical company Polichem S.A. found significant suppression of serum DHT after multiple doses (twice 1 mL daily) of the topical solution, comparable to that of oral 1 mg finasteride (around -70%) [21]. A follow-up study from the same investigators looked into the effects of a less frequent dosing regime (1 mL once daily) and lower dosages (0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 mL once daily) [22]. While dosing 1 mL daily still led to similar suppression of serum DHT as oral finasteride, the other dosage regimes led to decreases of 47.7, 44.1, 26.2 and 24.2 % for the 0.4, 0.3, 0.2 and 0.1 mL group, respectively. Scalp DHT suppression was favorable too for the topical application. One mg oral finasteride led to a decrease from baseline of 51.1 % in scalp DHT, the topical 0.4, 0.3, 0.2 and 0.1 mL groups saw a decrease of 54.3, 37.2, 46.8 and 52.3 %, respectively. As such, these lower doses show favorable pharmacokinetics: less suppression of serum DHT than oral finasteride while maintaining a similar suppression of scalp DHT.

Some other formulations have been produced as well, as there are many ways of doing this [23]. But the point here is that it’s possible to achieve substantial scalp DHT suppression while lowering DHT suppression in other tissues, as reflected in a smaller decrease in serum DHT levels. And, thus, it could have a more favorable safety profile while maintaining efficacy.

Clearly, topical finasteride is effective [24]. Some studies suggest it works at least as good as oral finasteride, or even slightly better—although they use different topical formulations of which it’s not always as clear to what extent they also suppress serum DHT. Regardless, a recent phase III trial concluded that a topical finasteride spray solution is similarly effective as oral finasteride, but with markedly lower systemic exposure and less impact on serum DHT (34.5 vs 55.6 % suppression) [25]. I think it’s a matter of time before a topical finasteride formulation gets approval by the FDA and before we know how its adverse effects relate to that of oral finasteride. As a final note, topical formulations can cause some local skin irritation of course (including pruritus [itching], burning sensation and erythema [redness]) [26].

Topical minoxidil

Minoxidil is a serendipitously discovered drug for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. It was initially used to treat hypertension under the brand name Loniten. However, doctors treating these patients noticed that it led to hypertrichosis, including scalp hair growth and reversal of androgenetic alopecia in some cases [26]. Of course, hypertrichosis, or excessive hair growth all over the body, is an unwanted effect. It needs to be directed to the scalp, ideally. As such it should come as no surprise that a topical formulation was produced and subsequently approved by the FDA for treatment of androgenetic alopecia in 1988.

Minoxidil works as a prodrug, that is, it first needs to be converted into an active metabolite. More specifically, it needs to be converted into minoxidil sulfate [27, 28]. In turn, this molecule acts on ATP-sensitive potassium channels by opening them. In the vascular smooth muscle cells, this leads to a lower electrical excitability of the cell. As a consequence, vasodilation of the blood vessels occurs—lowering blood pressure. While it’s mechanism of action in androgenetic alopecia remains to be elucidated, researchers think that it’s also somehow connected to this effect on potassium channels [27, 29]. For example, by enhancing blood flow to the dermal papilla. Regardless, evidence indicates that minoxidil shortens the telogen phase while increasing the anagen phase, and leads to reversal of miniaturization.

Topical minoxidil comes in concentrations of 2 and 5 %, with the 5 % working better and yielding an earlier treatment response than the 2 % one [30]. While it’s difficult to compare, oral finasteride appears to clearly be more efficacious than 2 % minoxidil. When looking at a meta-analysis listing the mean difference in hair count per square cm, oral finasteride led to a mean of 18.37 hairs, minoxidil 5 % twice daily 14.94 hairs, and 2 % twice daily 8.11 hairs. It’s assumed that there is a considerable % of men who don’t respond to treatment as a result of low expression of the enzyme (SULT1A1) responsible for conversion of minoxidil into its active sulfated metabolite. Since it takes several months before a treatment response becomes apparent, a diagnostic test to rule out nonresponders based on follicular sulfotransferase activity might hold promise [31]. However, this is not in clinical use yet. Another interesting development is that of adjuvants to increase SULT1A1 activity. A recent small-scale trial demonstrated a higher response rate in those combining minoxidil with a ‘SULT1A1 booster’ compared to a placebo [32].

Just as with use of oral minoxidil, topical minoxidil can also cause hypertrichosis. Common locations are the face, neck, hands, arms and legs. Some of it might be due to a systemic effect in sensitive individuals [33], although most of it is to be assumed to result from accidental exposure of these areas with the topical preparation. In some cases minoxidil might also induce some initial shedding. It’s thought that this is caused by minoxidil triggering hair follicles to transition from the telogen phase to the anagen phase [29]. Finally, concurrent use of (low-dose) aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) should be avoided, as it inhibits SULT1A1 activity [34]. This can negatively impact its efficacy.

Finally, it’s hard to say how well this drug works against androgenetic alopecia related to high doses of anabolic steroid use. In any case, the drug needs to be used for several months in order to assess its efficacy. Application of 1 mL twice a day is recommended.

Oral minoxidil

Oral minoxidil isn’t really prescribed much anymore, as other more efficacious and better tolerated blood pressure reducing medication has found its way to the clinic. However, it’s still prescribed occasionally in treatment of severe hypertension that’s not responding well to these other medications. For this purpose, dosages ranging from 5 to 40 mg daily are prescribed. Relatively common side effects are tachycardia (high heart rate), hypertrichosis (as mentioned earlier), and changes in the electrical activity of the heart as reflected on an electrocardiogram (ECG). For the purpose of treating androgenetic alopecia, lower dosages have been used in clinical trials, ranging from a mere 0.25 mg to 5 mg daily [35].

While it’s hard to compare its efficacy to other treatment options, it at least appears to be quite effective, especially in high dosages of 2.5 to 5.0 mg daily [35]. The authors of one trial using 5 mg daily in 30 men for 24 weeks suggested it clearly worked better than topical minoxidil and oral finasteride or dutasteride [36]. They based this on comparing their % of improved subjects (100 % in fact) to the results reported in a handful of other studies, as well as the increase in total hair count they found in their own study.

Nevertheless, while minoxidil did a seemingly good job, there were side effects too. Among which were abnormal ECG findings in 6 of the subjects; two presented with occasional premature ventricular contraction and four with asymptomatic T wave inversion on lead V1. It’s hard to indicate the clinical relevance of these findings, but T wave inversions can be found in a variety of issues related to the heart (e.g. ischemic heart disease and certain cardiomyopathies). Nevertheless, it can also be found in a small % of otherwise healthy individuals Either way, the authors dubbed it as a non-ischemic pattern and I suppose they thus found it a benign finding. Additionally, edema in the lower legs and feet was reported in 3 subjects. Finally, and perhaps not too unexpected, hypertrichosis was found in almost all subjects. Most of them weren’t too bothered by it, however.

The main point with oral minoxidil is that there’s a thin line between side effects and its beneficial effect on hair growth. And, of course, how much value you put into its hair growth-promoting effect versus its side effects. Sufficiently powered trials that evaluate the long term side effects of minoxidil are lacking, as such it seems prudent to use an as low as possible dosage of this drug if one would decide to give it a try.

Some final words

Oral finasteride in general is quite effective as a treatment option and, arguably, anything you have to take orally is very convenient in use as well. Topical finasteride can be preferred if oral finasteride yields to (sexual) side effects secondary to its systemic exposure. However, it can lack efficacy with concurrent anabolic steroid use that includes compounds other than testosterone or when testosterone is used in high dosages. Although it’s hard to say, topical minoxidil might be more efficacious under these conditions. Nevertheless, it, of course, doesn’t work for everybody (just to highlight: neither does finasteride). This is probably, at least in some part, related to insufficient activity of the enzyme that converts it to the active metabolite minoxidil sulfate. So-called “boosters” of this enzyme are in development and show some promising results. The oral use of minoxidil is probably a lot more convenient for most, as it doesn’t require the twice daily application on the scalp that the topical version does. However, long-term (>1 year) trials are lacking and there’s a thin line between side effects and its beneficial effects on hair growth. It’s ideally started at a low dosage, for example 0.25-0.5 mg daily, but—as far as I know—it’s only produced in tabs of 2.5, 5 and 10 mg. So good luck with that…To be on the safe side of things, it’s probably wise to do an ECG to see if it leads to any abnormalities (although it hasn’t been reported with these low dosages).

In my next article I’ll discuss some of the more experimental treatment modalities, such as topical androgen receptor antagonists and prostaglandins, PRP therapy, and Wnt signaling modulators.

References

-

Yamana, Kazutoshi, and Fernand Labrie. “Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride.” Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation 2.3 (2010): 293-299.

-

Gisleskog, Per Olsson, et al. “A model for the turnover of dihydrotestosterone in the presence of the irreversible 5α‐reductase inhibitors GI198745 and finasteride.” Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 64.6 (1998): 636-647.

-

Clark, Richard V., et al. “Marked suppression of dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia by dutasteride, a dual 5α-reductase inhibitor.” The journal of clinical endocrinology & metabolism 89.5 (2004): 2179-2184.

-

Dallob, A. L., et al. “The effect of finasteride, a 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor, on scalp skin testosterone and dihydrotestosterone concentrations in patients with male pattern baldness.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 79.3 (1994): 703-706.

-

Drake, Lynn, et al. “The effects of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopecia.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 41.4 (1999): 550-554.

-

Olsen, Elise A., et al. “The importance of dual 5α-reductase inhibition in the treatment of male pattern hair loss: results of a randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 55.6 (2006): 1014-1023.

-

Kaufman, Keith D., et al. “Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 39.4 (1998): 578-589.

-

Gupta, Aditya K., and Andrew Charrette. “The efficacy and safety of 5α-reductase inhibitors in androgenetic alopecia: a network meta-analysis and benefit–risk assessment of finasteride and dutasteride.” Journal of dermatological treatment 25.2 (2014): 156-161.

-

Harcha, Walter Gubelin, et al. “A randomized, active-and placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of different doses of dutasteride versus placebo and finasteride in the treatment of male subjects with androgenetic alopecia.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 70.3 (2014): 489-498.

-

Kanti, Varvara, et al. “Evidence‐based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men–short version.” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 32.1 (2018): 11-22.

-

Bergink, E. W., et al. “Comparison of the receptor binding properties of nandrolone and testosterone under in vitro and in vivo conditions.” Journal of steroid biochemistry 22.6 (1985): 831-836.

-

Schänzer, Wilhelm. “Metabolism of anabolic androgenic steroids.” Clinical chemistry 42.7 (1996): 1001-1020.

-

Schänzer, W., and M. Donike. “Metabolism of boldenone in man: gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric identification of urinary excreted metabolites and determination of excretion rates.” Biological mass spectrometry 21.1 (1992): 3-16.

-

Hirshburg, Jason M., et al. “Adverse effects and safety of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (finasteride, dutasteride): a systematic review.” The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology 9.7 (2016): 56.

-

Mella, José Manuel, et al. “Efficacy and safety of finasteride therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review.” Archives of dermatology 146.10 (2010): 1141-1150.

-

Trost, Landon, Theodore R. Saitz, and Wayne JG Hellstrom. “Side effects of 5‐alpha reductase inhibitors: A comprehensive review.” Sexual medicine reviews 1.1 (2013): 24-41.

-

Traish, Abdulmaged M. “Post-finasteride syndrome: a surmountable challenge for clinicians.” Fertility and sterility 113.1 (2020): 21-50.

-

Maksym, Radosław B., Anna Kajdy, and Michał Rabijewski. “Post-finasteride syndrome–does it really exist?.” The Aging Male (2019).

-

Trüeb, Ralph M., et al. “Post-finasteride syndrome: an induced delusional disorder with the potential of a mass psychogenic illness?.” Skin appendage disorders 5.5 (2019): 320-326.

-

Mazzarella, G. F., et al. “Topical finasteride in the treatment of androgenic alopecia. Preliminary evaluations after a 16-month therapy course.” Journal of dermatological treatment 8.3 (1997): 189-192.

-

Caserini, Maurizio, et al. “A novel finasteride 0.25% topical solution for androgenetic alopecia: pharmacokinetics and effects on plasma androgen levels in healthy male volunteers.” Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 52.10 (2014): 842-849.

-

Caserini, Maurizio, et al. “Effects of a novel finasteride 0.25% topical solution on scalp and serum dihydrotestosterone in healthy men with androgenetic alopecia.” International journal of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 54.1 (2016): 19.

-

Khan, Muhammad ZU, et al. “Finasteride topical delivery systems for androgenetic alopecia.” Current drug delivery 15.8 (2018): 1100-1111.

-

Suchonwanit, Poonkiat, Wimolsiri Iamsumang, and Kanchana Leerunyakul. “Topical finasteride for the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia and female pattern hair loss: a review of the current literature.” Journal of Dermatological Treatment (2020): 1-6.

-

Piraccini, Bianca Maria, et al. “Efficacy and safety of topical finasteride spray solution for male androgenetic alopecia: a phase III, randomised, controlled clinical trial.” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV.

-

Zappacosta, Anthony R. “Reversal of baldness in patient receiving minoxidil for hypertension.” The New England journal of medicine 303.25 (1980): 1480-1481.

-

Messenger, A. G., and J. Rundegren. “Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth.” British journal of dermatology 150.2 (2004): 186-194.

-

Buhl, Allen E., et al. “Minoxidil sulfate is the active metabolite that stimulates hair follicles.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology 95.5 (1990): 553-557.

-

Rossi, Alfredo, et al. “Minoxidil use in dermatology, side effects and recent patents.” Recent patents on inflammation & allergy drug discovery 6.2 (2012): 130-136.

-

Adil, Areej, and Marshall Godwin. “The effectiveness of treatments for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 77.1 (2017): 136-141.

-

Goren, Andy, et al. “Clinical utility and validity of minoxidil response testing in androgenetic alopecia.” Dermatologic therapy 28.1 (2015): 13-16.

-

Dhurat, Rachita, et al. “SULT1A1 (Minoxidil Sulfotransferase) Enzyme Booster Significantly Improves Response to Topical Minoxidil for Hair Regrowth.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology (2021).

-

Peluso, A. M., et al. “Diffuse hypertrichosis during treatment with 5% topical minoxidil.” British Journal of Dermatology 136.1 (1997): 118-120.

-

Goren, A., et al. “Low‐dose daily aspirin reduces topical minoxidil efficacy in androgenetic alopecia patients.” Dermatologic therapy 31.6 (2018): e12741.

-

Randolph, Michael, and Antonella Tosti. “Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: A review of efficacy and safety.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 84.3 (2021): 737-746.

-

Panchaprateep, Ratchathorn, and Suparuj Lueangarun. “Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil 5 mg once daily in the treatment of male patients with androgenetic alopecia: an open-label and global photographic assessment.” Dermatology and therapy 10.6 (2020): 1345-1357.

About the author

Peter Bond is a scientific author with publications on anabolic steroids, the regulation of an important molecular pathway of muscle growth (mTORC1), and the dietary supplement phosphatidic acid. He is the author of several books in Dutch and English, including Book on Steroids and Bond's Dietary Supplements.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.