The following is an overview of the scientific literature on the relationship between anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) and aggression. It is intended as a brief informational review without references to the larger literature from which it draws. A more in-depth review of these issues can be found in a series of articles on this topic I wrote several years ago that are available at MESO-Rx and include voluminous scientific references. An expanded version of this review is likely to appear in a fully-referenced form in the future.

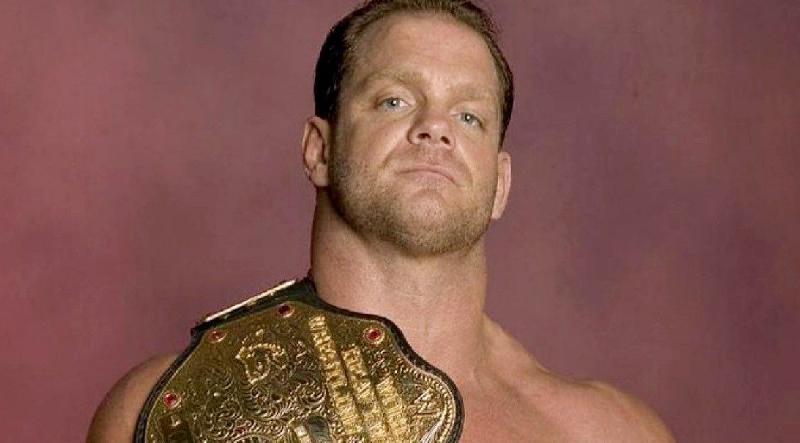

The Chris Benoit Murder/Suicide – What It Can and Cannot Tell Us

In events like the Chris Benoit family tragedy the alleged perpetrator’s characteristics inevitably suggest hypotheses and the search for confirming evidence begins. Anabolic steroids or anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) were blamed before prescription AAS were found, as researchers and commentators alike called forth the popular AAS-‘roid rage connection. Such narrow reasoning backward from the act and actor to the cause shows that jumping to conclusions can seem like reasonable inference. One commentator even noted her preference for blaming steroids over accepting that a person could commit this act, as if assuming that, in the absence of some drug influence, such an act would be a conscious decision, that the only possible causes were drugs or volition. It is likely that research and data will not change these views; still they should not be forsaken.

The facts are: anabolic steroids are illegal. They are powerful drugs, yet research shows the vast majority who use them do so without physical or psychological harm. Some users show negative psychological effects, although such symptoms’ direct relationship to AAS is unclear. This lack of clarity and the gap between science and society makes it important at such times to look to science and question reflexive assumptions; in doing so I do not advocate AAS use, but that we pay attention to science.

Case studies, even tragic ones, may suggest associations among events, like drug use and behavior, but are not proof of causality. Too many idiosyncratic factors confound the observed associations; their salience belies their scientific value. Scientific knowledge is built over time with studies using groups that represent the population or process, not the individual. Science looks for convergence among findings. It uses experiments to examine cause-effect relationships. Science often reveals that what seems to be so is not. These various designs have been used to explore the AAS-aggression relationship and no scientist can say absolutely that AAS did or did not cause this one event.

There are no controlled scientific studies of “’roid rage”, a popular but not scientific term. The AAS-aggression relationship has been studied and the research can be summed up as inconsistent at best and largely unsupportive of the hypothesis. AAS do not inevitably cause aggression. No critical dose that invariably triggers aggression has been identified. When aggression is observed among AAS users, it is within a minority, the effect is not uniform at any dose, and it is not clearly related to blood levels of hormones (Hence, the anticipated toxicology report will be insufficient in a scientific sense to settle this question in the Benoit case).

At a mean level, users self-administering AAS may report higher levels of irritability, hostility or aggressivity than non-users. But users and non-users differ in many ways and AAS self-administration could be influenced by pre-existing aggressive tendencies or a desire for increased aggression, both of which can predict drug-related behavior. Psychology has long known that the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, a fact that may be pertinent to this case. For instance, on average AAS users have been reported to be more aggressive than non-users whether taking AAS or not, suggesting that such characteristics may predate/predict AAS use and that AAS could facilitate the expression of existing tendencies. Unfortunately, the true longitudinal data needed to answer this question of pre-existing differences and AAS use are lacking.

Randomly-assigned participants administered supra-physiological doses of AAS in placebo-controlled experiments exhibit negligibly increased aggressive responding; such assignment controls for potential individual differences. Self-reported changes on aggression scales are typically minimal if they do reach statistical significance. A laboratory analog task (the Point Subtraction Aggression Paradigm; PSAP) in which punitive responses to an alleged competitor’s aggressive responding index aggression has shown some reliable but minor effects (and marijuana users in withdrawal scored similarly to those administered AAS). Behavioral observations by significant others note minimal behavior changes. Some increases in aggression have been seen in participants administered placeboes, suggesting expectation may influence AAS-related behavior. However, such human experiments not only lack adequate active placeboes (normally using only inert oils) to adequately determine AAS direct effects, but cannot ethically administer “real world” AAS doses.

Animal studies allow for larger AAS doses to be used, but their results often fail to generalize to the real world. For example, one study (Ricci et al., 2007, in Behavioral Brain Research) cited in the discussion of this tragedy administered AAS doses (e.g., a total 5mg/kg/day of several AAS) over the complete adolescent period of animals (30 days) and effects on aggression that lasted past cessation. However, the equivalent treatment for a 100 kg human would be 3.5 grams of AAS per week non-stop for years. That regimen does not reflect real world AAS use, either by typical dose or pattern of use, nor does it conform to any known parameters in the current case. On the other hand, consistent with human research, AAS-aggression in animals differs as a function of individual characteristics. Steroid administration increased overall aggression in existing non-human primate groups, but the effect varied by social status; dominant males’ aggression increased while lower-ranking males’ submissiveness increased, suggesting an interaction between AAS and context/characteristics.

It is clear that there is scant scientific evidence that AAS directly cause aggression. What is often presented as evidence lacks external validity. It is likely that any drug, illicit or prescription, administered in high doses for a number of years would have deleterious effects. Ultimately, a minority of self-selected AAS users may show increased aggression, although the mechanism is not clear. Experimental designs with random assignment control for self-selection and find minimal if any evidence for a relationship. There is no consistent relationship between symptoms and blood levels of AAS. The discrepancies between the survey and experimental (including blood levels) findings suggest a need to know more about how AAS interact with individual characteristics and circumstances. That is the state of the science on this issue.

There are an estimated 1 – 3 million AAS users in the US. Ghastly acts such as the Benoit case are rare and, as science would predict, their association with AAS use is virtually non-existent. Many other characteristics are far more predictive of such events. It cannot be said with certainty whether AAS contributed to this tragedy or not. If they were involved, AAS were not a sole contributor but part of a larger set of characteristics and circumstances. There is no scientific evidence to suggest that AAS alone caused this behavior and they are obviously not necessary for such events to occur. The evidence does suggest that most AAS users do not become aggressive. Nonetheless, science will, at best, play a small part in society’s verdict on Benoit and AAS in this tale and it will be another instance where a drug is linked to a heinous act by association and, therefore, the untested popular notions that dominate the headlines today will be reinforced.

If blame were put aside for a moment, there are important lessons unrelated to such simplistic notions that the Benoit tragedy can impart to society. WWE officials say that Benoit tested negative for AAS in April. If AAS is cast as a lone villain, then that was a clean bill of health at that time. But, had society at large and the surveillance program to which Mr. Benoit was subject been at least as concerned with his emotional, familial, and social situation as with his potential AAS use, this event may have been averted. Both science and practicality suggest that, at most, AAS use should be one of multiple foci here, as it should have been in April or before. No drug test in April could have told us enough about this family’s life nor will any toxicology report that might follow.

If AAS are blamed and the richness of these lives ignored, then the opportunity to prevent such rare events goes unrealized. Singling out a drug to blame leads to fiery rhetoric, congressional hearings, prohibition and scare tactics; none of these have succeeded in curbing drug use, especially among those at greatest risk for harm. Most AAS users do not experience negative effects and hence distrust the message and the messengers, perhaps most notably among those who should listen. Research has shown this many times. Blaming AAS diverts focus from potential indicators of risk and predictors of harmful outcomes. This is where science might be most helpful in dispelling simplistic notions and in working toward more effective risk identification, targeting of limited resources and reducing associated harms.

About the author

Jack Darkes, Ph.D. is a Clinical Psychologist and currently the Director of the Psychological Services Center in the Department of Psychology at the University of South Florida. He is well-known and respected both nationally and internationally for his research on psychological factors related to substance use and abuse. He has applied his experience to an examination of the use and behavioral effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) and his writings on AAS are well-known to readers of various internet fitness and bodybuilding websites.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.