The overwhelming success of Kenyan distance runners over the past twenty-five years has stimulated a great deal of speculation about the origins of their remarkable performances. Living at high altitude, adolescent circumcision rituals, a legacy of cattle raiding, training up and down hills, body structure (including “bird-like legs”) – these and other potential explanatory factors have been discussed endlessly over many years. The prospect of finding a genetic explanation for Kenyan dominance has haunted this discussion from the beginning. The fact that most of the elite runners come from a single tribe, the Kalenjin, has long pointed in the direction of some kind of genetically programmed advantage. The late Bengt Saltin, a renowned Swedish sports scientist, looked at the comparative research on Scandinavia and Kenyan runners and concluded: “There are definitely some genes that are special here.” To which the great Kenyan runner Mike Boit added: “The genetic inheritance is there.” i

The genetic hypothesis belongs to a larger evolutionary narrative about the sources of a superior African athleticism. The idea of an African “tropical nature” has long presented Africa as a crucible of biological energy and innovation that has no counterpart anywhere else on earth. Africa is, in short, a biological hothouse where anything can happen. A classic formulation of this evolutionary narrative comes from the former elite American marathoner Kenny Moore:

“On Christmas morning you awaken to the cries of hawks and the songs of children, and lie there thinking about how Africa can seem a sieve of afflictions through which only the hardy may pass. The largest, fastest, wildest, strangest beasts are here. Every poisonous bug, screaming bird and thorned shrub has arrived at this moment through the most severe competition. They have a history of overpowering more gentle environments. You think of lungfish, of killer bees, of AIDS. Of men. Of the great Repo men, the Nandi, turning from their raiding and become runners.” ii

Fort many years the power of this evolutionary narrative insulated the Kenyan world-beaters from doping accusations. During most of the era of Kenyan dominance, the theme of doping has either been absent or not taken seriously. In 1997, for example, an American expert on Kenyan runners, John Manners, argued that there was no evidence of Kenyan doping and that “the idea that drugs are fueling Africans’ recent superiority is absurd on its face.” There were, he said, no drugs in Kenya. The elite runners’ training sojourns at a camp in Italy, run by a hugely successful marathon coach, Dr. Gabriele Rosa, did give them access to “the latest in sophisticated pharmacology,” but that proved nothing. Kenyan runners who refused to take legal anti-malarial drugs would surely disdain illegal performance enhancers. “In fact,” Manners wrote, “I’ve found their attitude to both these types of medication to be strangely similar; they’re both considered mambo ya wazungu–white man’s business, not an appropriate concern for an African. They may not say it in so many words, but the thought seems to be, ‘Let the frail Europeans and Americans dose themselves with these chemicals. Africans have always managed without them. We don’t need them’.” iii

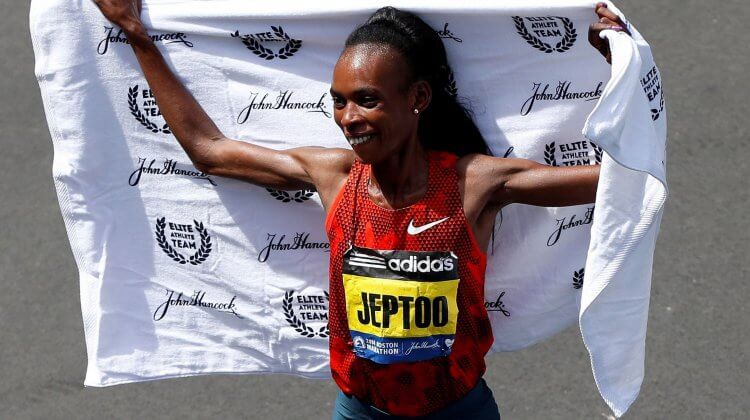

In early November 2014 came the news that Rita Jeptoo, the world’s best female marathoner, had tested positive for the blood-boosting hormone erythropoietin (EPO). Anyone who was shocked by this announcement should not have been. Over the past two years, many Kenyan athletes have tested positive for doping substances, and the positive tests have been accumulating for longer than that. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) has expressed its dissatisfaction with Kenyan officials’ lack of vigilance. The Kenyan government has set up a task force to make up for lost time.

The Kenyan doping crisis marks the end of an era. The notion that doping is a “white man’s business” has been revealed to be an illusion. The evolutionary narrative survives, but doping has taken some of the wind out of its sails.

When Jeptoo’s Italian agent, Federico Rosa – son of Gabriele — was asked whether he thinks current marathon records are clean, he replied: “What can I say? I can say I hope yes, I hope they’re clean. That’s all I can say. That’s my big hope.” iv

Endnotes

- “Controversial Danish research claims to explain African running dominance,” Agence France-Presse (November 26, 2014).

- Kenny Moore, “Sons of the Wind,” Sports Illustrated (February 26, 1990): 79.

- John Manners, “The Drugs Question” (August 28, 1997). [http://www.kenyarunners.com/pages/167372/]

- “Straight Dope: Exclusive Interview With Jeptoo’s Agent Federico Rosa”

(November 4, 2014). [http://running.competitor.com/2014/11/news/rita-jeptoos-agent-federico-rosa_117410]

About the author

John Hoberman is the leading historian of anabolic steroid use and doping in sport. He is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of many books and articles on doping and sports. One of his most recent books, “Testosterone Dreams: Rejuvenation, Aphrodisia, Doping”, explored the history and commercial marketing of the hormone testosterone for the purposes of lifestyle and performance enhancement.