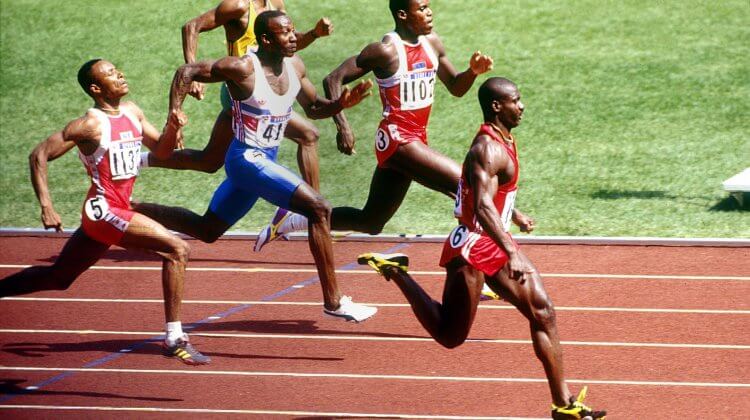

Experimentation with chemical substances for the purpose of boosting athletic performance dates from the last decades of the nineteenth century. Ethical disapproval in sports circles of what came to be called “doping” dates from the 1920s. Societal disapproval of athletic doping on a larger scale has developed slowly over the past half-century, along with the global doping epidemic that began during the 1960s. This is when increasing numbers of athletes began to use anabolic steroids to improve their performances. The crucial intensification of societal condemnation of doping on a global scale was catalyzed by the Ben Johnson doping scandal that erupted in September 1988 during the Seoul Olympic Games. The second great catalyzing event of this kind was the massive doping scandal that almost destroyed the 1998 Tour de France. The Tour scandal also coincided with the first public indications that Major League Baseball players too might be interested in anabolic steroids. Over the past ten years, the American sporting public has become saturated with news about the doping practices of these popular athletes.

The progressive stigmatizing of doping is one historical context within which we can pose the question: Do Drug-Taking Athletes Feel Guilt? But there is a second and equally important historical context that is required to help us make sense of questions about doping and issues regarding personal responsibility and guilt. Modern high-performance sport as we know it originated in a Victorian athletic culture that cultivated ethical conduct rooted in social norms and the virtue of self-control. In the course of the past century and a half, the high-performance sports culture that was born in England has shed most of its ethical core while retaining the familiar moral rhetoric about building “character” and promoting “fairness.” The doping epidemic that has spread throughout high-performance sport since the 1960s is the product of mankind’s encounter with limits to athletic performance that are inherent in the human body. High-performance athletes have become caught between the opposing mandates of ethical conduct on the one hand and demands for extreme performances on the other. The doping practices of many elite athletes are thus responses to these irreconcilable demands for both self-restraint and extreme athletic efforts that can be literally inhuman.

The third socio-historical context we must examine is the world of global elite sport itself, as exemplified by the Olympic Games and the hundreds of national sports institutions around the world that exist to strive for Olympic medals. The global sports world is a very complex organism that is administered by powerful financial and political interests and that involves many conflicts of interest. International sports organizations such as the IOC and FIFA constitute an offshore enterprise zone for power- and status-hungry opportunists for whom doping is a public-relations problem rather than a threat to the integrity of sport. FIFA drug-testing, for example, has not turned up a single doping positive in the five World Cups that have been played since 1998.

Doped athletes are thus very small cogs in the enormous machine that lives off of their performances. Yet the enormous imbalance of power between doped athletes and the sports establishment that prosecutes them is routinely ignored in media coverage of doping scandals. Media discourse on doping focuses almost entirely on the individual malefactor and employs a vocabulary that is both moralizing and at times quasi-religious: one reads about “rehabilitation,” “redemption,” and even “resurrection.” The Vatican critique of doping initiated by Pope Pius XII in 1955 continues to the present day. Even more than they are legal matters, high-profile doping cases are spectacles of moral transgression in which the accused athlete is the only protagonist under the spotlight. And as transgressors, they are expected to feel guilt.

About the author

John Hoberman is the leading historian of anabolic steroid use and doping in sport. He is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of many books and articles on doping and sports. One of his most recent books, “Testosterone Dreams: Rejuvenation, Aphrodisia, Doping”, explored the history and commercial marketing of the hormone testosterone for the purposes of lifestyle and performance enhancement.