While athletes who dope are usually expected to feel guilt pangs, the exception to this rule is when an observer concludes that dopers in general, or a particular doper, may not have consciences at all. In 2010 Dick Pound, who served as president of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) from 2000 until 2007, called doping athletes “sociopathic cheats [who] deserve to be dealt with accordingly.” This comment seemed to be based on the mistaken assumption that entire cohorts of athletes, whether cyclists or shot-putters or sprinters or weightlifters, are sociopaths. Ascribing this sort of abnormality to a genuinely abnormal athlete strikes me as more realistic. In this vein, in January 2013 I wrote on CNN.com: “I have come to doubt whether [Lance Armstrong] is capable of genuine contrition…. Is it really possible to acquire a conscience overnight? Can a person who has long-demonstrated reckless self-assertion, a lack of empathy, cold-heartedness, egocentricity, superficial charm and irresponsibility suddenly repent after months of hostile intransigence? One is tempted to say no, since this ensemble of traits bears a disturbing similarity to the psychopathic personality.” [180]

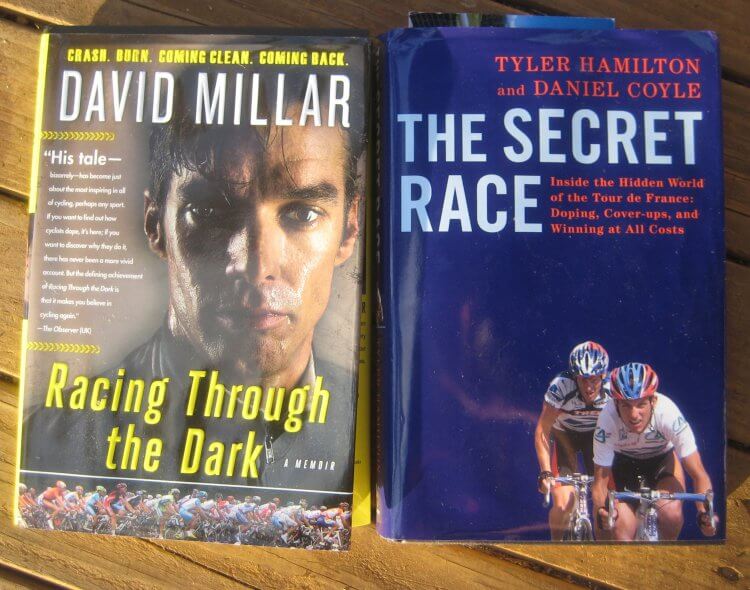

Lance Armstrong’s unusual status as a publicly guilt-free doper contrasts with that of some other elite cyclists who have been caught doping and have told their stories in often wrenching detail in their autobiographical exercises in self-examination. In The Secret Race (2012), Tyler Hamilton, Armstrong’s former teammate, describes the course of his emotional development before and following his exposure as a doper. i

The Secret Race is not what one would call a straightforward exercise in repentance. For one thing, Hamilton’s wide-ranging and impressively honest account of what it’s like to live and breathe the atmosphere of cycling at the ultimate level of the Tour de France addresses far more than the ethical dilemmas associated with doping. According to Hamilton, cycling offers a range of intense experiences that make all the suffering more than worth it. “We love our sport because of its purity,” he says: “it’s just you, your bike, the road, and the race.” [34] There are “the mysterious surprises that can happen when you give it all you’ve got.” [22] Indeed, just surviving the ordeal can bring a deep sense of fulfillment. And along with the satisfactions achieved in a state of isolation, there is a fellowship rooted in “the ancient code of bike-racing chivalry” [194]. “There is no friendship in the world like the friendship of being on a bike-racing team” [51] But how, one might ask, do the gratifications of this male bonding manage to coexist with the tawdry self-deceptions of the doping culture that sometimes gave Hamilton the creeps?

As for Hamilton’s conscience, The Secret Race offers an opportunity to watch the author slide inexorably toward the emotional breakdown and intense feelings of shame that awaited him. Guilt had once been “an emotion most of us had given up long ago.” [114] After his exposure as a doper, the mental dam broke and feelings of shame were followed by a deep depression from which he eventually recovered.

While Hamilton speaks honestly about guilt and shame, they do not engulf him. Having recovered from depression, the semi-repentant cyclist has not lost his spunk: “You can call me a cheater and a doper until the cows come home. But the fact remains that in a race where everybody had an equal opportunity, I played the game and I played it well.” [196]

Those looking for a deeper grasp of ethics than Tyler Hamilton has to offer can turn to David Millar’s Racing Through the Dark (2011). ii Millar’s memoir of a repentant doping cyclist confirms once again the sobering truth that the awakening of a doper’s conscience requires that he or she be caught, humiliated, and thereby provided with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to acquire a kind of self-knowledge the glorious lives of champions do not make possible.

Endnotes:

- Tyler Hamilton and Daniel Coyle, The Secret Race (New York : Bantam Books, 2012).

- David Millar, Racing Through the Dark (London: Orion, 2011).

About the author

John Hoberman is the leading historian of anabolic steroid use and doping in sport. He is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of many books and articles on doping and sports. One of his most recent books, “Testosterone Dreams: Rejuvenation, Aphrodisia, Doping”, explored the history and commercial marketing of the hormone testosterone for the purposes of lifestyle and performance enhancement.