Weightlifting Convicts as a Threat to Society

One of the less visible contests between policemen and criminals occurs in an indirect fashion in station houses and prisons. This contest takes the form of weightlifting, of “working out,” and although the law-enforcers have the better equipment, the sheer ingenuity of the weight-lifting law-breakers makes it a fair competition, if a competition is what it is. According to an ex-convict who has produced a fine anthropological analysis of the weightlifting culture behind bars, “lifting weights is practically a religion in American prisons.” i In fact, a genuine devotion to pumping iron is evident on both sides of the legal divide that separates the guardians of the law from those who require guarding. Is it possible that the “cultural acceptance of bodybuilding” in the police community has a primal link to what animates the iron-obsessed prisoners? ii

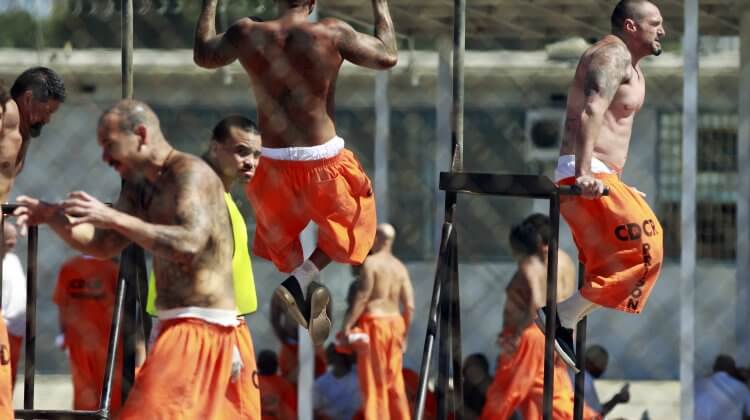

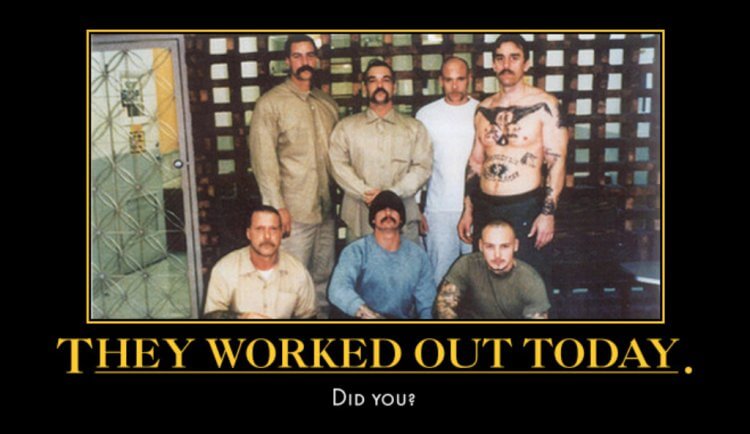

The idea of a cops-against-convicts bodybuilding competition is encouraged by the graphic posters that hang in some police stations. “He’s Pumping. Are You?” reads one that shows a well-built convict doing a bench-press. “They Worked Out Today. Did You?” reads another which is graced by a photo of seven thuggish-looking inmates, including a bare-chested muscleman with a tattoo-covered torso. This concern about the heavily muscled adversary is not reciprocated by the men behind bars. The prisoners who bulk up do not display photos of bulked-up cops on their makeshift gym walls. As the ex-convict anthropologist points out: “It’s part of the macho prison culture to lift weights, and to be manly and tough.” In practical terms, convicts aren’t worried about what hard-muscled cops might do to them on the outside. It is the cops who are apprehensive about convicts who seem to have all day to muscle up in preparation for the havoc they will be able to wreak when they get out.

The balance of power between these weightlifting adversaries was thrown out of kilter in the mid-1990s by conservative politicians bent on removing certain amenities of prison life. The No Frills Prison Act (HR 663), subtitled “Amendment to Prevent Luxurious Conditions in Prisons,” was introduced in 1994. Many prisons now banned smoking, R-rated movies, conjugal visits, and pornography. Despite its contribution to inmates’ physical and mental health, weightlifting was added to the list of banned “luxuries.” As one legislator put it: ““there is a psychological mind-set to being bulked up and I don’t like that mind-set in a criminal.” More muscle made criminals more dangerous. And where did this concern about muscled-up convicts come from? “Politicians passed many of these measures as a response to popular portrayals of prison weightlifting in the media.” Alan Tepperman has argued that the infamous Willie Horton ad of 1988, Robert De Niro’s “iron-pumping redneck” character in Cape Fear (1991), the 1992 Mike Tyson rape trial, and the 1994 Rikers Island prison riot, where prisoners were reported to have hit guards with barbells, all contributed to “the moral panic surrounding prison weightlifting.”iii And then, in 1996, the Princeton social scientist John DiIulio popularized his hysterical prediction that (black) juvenile “superpredators” were about to unleash an unprecedented crime wave upon American society. Fantasy-driven muscle profiling had acquired a toehold in the popular imagination.

Interestingly, steroids played no role in the overheated public discussion of weightlifting criminals. Two decades ago the vast majority of Americans had no idea of the sheer scope of steroid use in various social venues. More important, however, was the ease with which popular media conjured up the image of the “muscle monster” behind bars. (The protein deficit the incarcerated lifters have to overcome was never mentioned.) These days steroid-pumped convicts do not seem to pose much of a threat. In 2013, for example, a strongman contest at Addiewell prison in Scotland was cancelled after the contestants heard they would be tested for steroids. The private company that runs the prison expressed its regrets: “The gym is probably the main thing in prison that helps inmates pass their time.” iv

Endnotes

- Daniel Genis, “An Ex-Con’s Guide to Prison Weightlifting” (May 6, 2014).[http://fittish.deadspin.com/an-ex-cons-guide-to-prison-weightlifting-1571930353]

- “Police Juice Up on Steroids to Get ‘Edge’ on Criminals,” ABCNEWS (October 18, 2007).

- Alan Tepperman, “We will NOT Pump You Up: Punishment and Prison Weightlifting in the 1990.” [http://www.academia.edu/552799/We_Will_NOT_Pump_You_Up_Punishment_and_Prison_Weightlifting_in_the_1990s]

- “Cons pull out of prison strongman contest over fears they’ll be busted for taking asteroids,” Daily Record (April 28, 2013). [http://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/cons-pull-out-prison-strongman-1858129]

About the author

John Hoberman is the leading historian of anabolic steroid use and doping in sport. He is a professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of many books and articles on doping and sports. One of his most recent books, “Testosterone Dreams: Rejuvenation, Aphrodisia, Doping”, explored the history and commercial marketing of the hormone testosterone for the purposes of lifestyle and performance enhancement.