Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing is limited

- You have a limited number of page views remaining

- 2 guest views remaining

- Register now to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

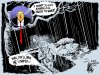

Trump Timeline ... Trumpocalypse

- Thread starter CdnGuy

- Start date

I wish Fauci would just quit. He knows the pres is an imbecile. He knows cheeto fucked all this up. Why stay on such a losing team?

RUFKM ...

This is such a joke. It’s amazing. Obviously the American people are dumber than toast.

While Americans died of the modern plague, President Trump sang happy birthday to a fading Fox News personality. On March 7th, a who’s who of the Republican establishment gathered at Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s lavish retreat in Florida, for the 51st-birthday party of Kimberly Guilfoyle, one of the former co-hosts of The Five, and now the girlfriend of Donald J. Trump Jr. All the usual suspects were there, including Trump’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani and Sen. Lindsey Graham; Tiffany Trump; Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner; and Trump’s younger son Eric and his wife, Lara. They sang happy birthday to Guilfoyle and lit a big sparkler. At the end, she pumped her fist and shouted “Four more years!” This is what passes for a cozy family celebration in Trumpland. But out in the real world, darkness was falling fast.

There were already 100,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, around the world, and 3,600 people had died. In the U.S., more than 100 new cases had been reported that day, a rate that was doubling every three days. Other nations knew how serious this was: By that time, China had shut down major cities, all but quarantining 760 million people. Singapore and Hong Kong and South Korea had put in aggressive travel restrictions and testing procedures. In the U.S., fear was rising. South By Southwest, the giant music/tech conference in Austin had just been canceled. Grocery stores were stripped in panic buying. On Wall Street, stocks were in free fall.

Trump knew all this. In fact, he knew a lot more. He had been getting daily intelligence reports for two months, warning him about the risk of a pandemic. It’s impossible to believe he had not been told that COVID-19 was at least 10 times more deadly than the flu, or that it was passed human to human with a just touch or a cough. A top White House adviser had already warned that a full-blown pandemic could imperil the lives of millions of Americans. Virtually every public-health expert in the world was speaking out, warning politicians and community leaders what was about to hit us.

Nevertheless, since the moment the outbreak was first publicized in January, Trump had been doing nothing but downplaying it. To him, the pandemic was merely another plot to sabotage him. “They’re trying to scare everybody . . . cancel the meetings, close the schools — you know, destroy the country,” he told his guests that weekend. “And that’s OK, as long as we can win the election.”

Before the party, Trump played a round of golf. Then he had dinner at Mar-a-Lago with populist, right-wing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, one of the few people in the world who can challenge Trump as the king of coronavirus denial. (Bolsonaro dismissed the illness as “a little flu.”) In what you might call God’s cruel little joke, three of Bolsonaro’s aides who attended the dinner would later test positive for the coronavirus. At least one other person who was at Mar-a-Lago also tested positive, as did Miami Mayor Francis Suarez, who met with Bolsonaro at a different event in Miami.

It was a Trump-branded petri dish that night. ...

What’s stunning about this is not the degree to which Trump — a self-confessed germophobe who often douses himself with hand sanitizer after a handshake — put himself at risk. By hosting this party, he also put his friends and his family at risk. It’s a chilling glimpse into the psyche of the president of the United States, a man who has demonstrated, over and over, that he thinks science is a church for losers and that there isn’t any predicament he can’t bully or con his way out of. When the full story of this pandemic is written, it will be clear that Trump not only failed in protecting 329 million Americans from a deadly virus but that he even failed to protect his own sons and daughters.

And 30% of the US believe this virus was manufactured in a lab and escaped on someone’s Scooby-Doo lunch box

No fucking wonder trump was able to become president.

No fucking wonder trump was able to become president.

Those who complain about the media’s relentless focus on President Trump during a pandemic have yet to internalize the horrendous reality of his pandemic response: Trump’s failures of leadership and character have increased the death toll and continue to threaten lives.

For me, that is a difficult sentence to write. Having spent time in the executive branch, I realize how complicated presidential decisions can be. America’s chief executives are often forced to make momentous choices, based on scant information, under the pressure of a ticking clock. It is easier to attack such decisions than to make them.

But the fact of Trump’s deadly negligence is now demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt. Detailed investigative articles in The Post and New York Times have established that there were six weeks of denial and dithering between a credible warning about the virus and decisive action by the president. It is now evident that Trump:

· ignored early intelligence reports of a possible pandemic;

· delayed the ramp up of practical preparations;

· was often more focused on political considerations, on the news cycle and on stock market performance than on epidemiological reality;

· deceptively played down what he knew to be a rising threat;

· coddled China when it should have been confronted;

· instinctively distrusted experts and seemed unable to absorb simple information and sound advice;

· lashed out at aides who took the crisis seriously;

· shifted reluctantly and belatedly from a strategy of containment to mitigation;

· is strangely obsessed with unproven treatments for the novel coronavirus; and

· has systemically lied about the promptness of his own response.

These accounts reveal a White House staffed by incompetent loyalists, distracted by turnover and riven by feuds. A White House carefully pruned and shaped to resemble the chaos in Trump’s mind.

...

To appreciate what might have been if our government had acted quickly and correctly, we first have to estimate the coming costs to the economy given how little this administration actually did. The only hard economic data available today to gauge those effects are initial unemployment claims. Even so, they can give us a sense of our actual and prospective job losses, which can be converted into the impact on the overall economy or GDP.

In the final two weeks of March and the first week in April, jobless claims jumped about 17 million. Most of the country is likely to remain shut down for a minimum of another month, which suggests that a comparable number of people could lose their jobs during the rest of this month. This would increase unemployment by some 35 million for a jobless rate of nearly 27 percent. This forecast is midway between a recent estimate by the president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, who expects to see 40 million unemployed (a 30 percent jobless rate), and the forecast by Trump’s treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, that the unemployment report for April will show a total of 30 million new jobless individuals (a 20 percent rate).

We can estimate the broad economic costs associated with such dramatically high unemployment. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that in 2019, 150,935,000 working Americans produced the country’s GDP, and according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, that GDP in 2019 totaled $21,428 billion. So each working person, on average, was responsible directly and indirectly for $141,966 in GDP. If the pandemic costs 35 million working Americans their jobs, GDP should fall by some $4,969 billion, or 23.2 percent on an annual basis – from March 2020 through February 2021. If the collapse in employment lasts from March through August, GDP in that period would fall by $2,485 billion or 11.6 percentage points.

The other element at work now is that Congress and the administration have authorized about $2 trillion in new spending to help slow the collapse in jobs. It’s far short of a cure. Much of those funds won’t flow into the economy before May and June. Even with additional funds to extend small business loans (read: grants) to employers who preserve jobs, one-quarter or less of the total funds appropriated by Congress are targeted to employment. Let’s assume here that the loans and the other emergency spending are sufficient to enable 10 million furloughed workers to return to their jobs, but the crisis drags on, again, through February 2021. That would leave 25 million additional Americans unemployed, driving down GDP by $3,549 billion, or 16.6 percentage points on an annual basis.

If, somehow, everything returns to normal after six months, the government’s spending will ultimately prove more effective at tiding workers over until the pandemic ends. But GDP losses would still be $1,775 billion or 8.4 percentage points. And that still daunting scenario assumes not only that the flood of government spending turns around the economy, but also that the virus dissipates and we develop treatments to contain any resurgence.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 186

- Views

- 5K

- Replies

- 35

- Views

- 621

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 1K