Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing limit reached

- You have reached the maximum number of guest views allowed

- Please register below to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

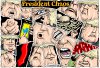

Trump Timeline ... Trumpocalypse

- Thread starter CdnGuy

- Start date

Conservatives say we've abandoned reason and civility. The Old South used the same language to defend slavery.

I grew up in a conservative family. The people I talk to most frequently, the people I call when I need help, are conservative. I’m not inclined to paint conservatives as thoughtless bigots. But a few years ago, listening to the voices and arguments of commentators like Shapiro, I began to feel a very specific deja vu I couldn’t initially identify. It felt as if the arguments I was reading were eerily familiar. I found myself Googling lines from articles, especially when I read the rhetoric of a group of people we could call the “reasonable right.”

These are figures who typically dislike President Trump but often say they’re being pushed rightward — sometimes away from what they claim is their natural leftward bent — by intolerance and extremism on the left. The reasonable right includes people like Shapiro and the radio commentator Dave Rubin; legal scholar Amy Wax and Jordan Peterson, the Canadian academic who warns about identity politics; the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt; the New York Times columnist Bari Weiss and the American Enterprise Institute scholar Christina Hoff Sommers, self-described feminists who decry excesses in the feminist movement; the novelist Bret Easton Ellis and the podcaster Sam Harris, who believe that important subjects have needlessly been excluded from political discussions. They present their concerns as, principally, freedom of speech and diversity of thought. Weiss has called them “renegade” ideological explorers who venture into “dangerous” territory despite the “outrage and derision” directed their way by haughty social gatekeepers.

So it felt frustrating: When I read Weiss, when I listened to Shapiro, when I watched Peterson or read the supposedly heterodox online magazine Quillette, what was I reminded of?

The reasonable right’s rhetoric is exactly the same as the antebellum rhetoric I’d read so much of. The same exact words. The same exact arguments. Rhetoric, to be precise, in support of the slave-owning South.

...

If somebody says liberals have become illiberal, you should consider whether it’s true. But you should also know that this assertion has a long history and that George Wallace and Barry Goldwater used it in their eras to powerful effect. People who make this claim aren’t “renegades.” They’re heirs to an extremely specific tradition in American political rhetoric, one that has become a dangerous inheritance.

Part of Trump’s genius has been to pursue for a lifetime the features that have sustained narrative contagion: showcasing glamor, surrounding himself with apparently adoring beautiful women, and maintaining the appearance of vast influence.

Trump had firmly embraced this career strategy by 1983, when an article in the New York Times entitled “The Empire and Ego of Donald Trump” reported that he was already, in that year, “an internationally recognized symbol of New York City as mecca for the world’s super rich.”

Consider his interest in professional wrestling – a form of entertainment that attracts crowds who by some strange human quirk seem to want to believe in the authenticity of what is obviously staged. He has mastered the industry’s kayfabe style and uses it effectively everywhere to increase his contagion, even going so far as to participate in a fake brawl in 2007.

...

During a recession, people pull back and reassess their views. Consumers spend less, avoiding purchases that can be postponed: a new car, home renovations, and expensive vacations. Businesses spend less on new factories and equipment, and put off hiring. They don’t have to explain their ultimate reasons for doing this. Their gut feelings and emotions can be enough.

So far, with his flashy lifestyle, Trump has been a resounding inspiration to many consumers and investors. The US economy has been exceptionally “strong,” extending the recovery from the Great Recession that bottomed out just as Barack Obama took over the US presidency in 2009. The subsequent US expansion is the longest on record, going back to the 1850s. Ultimately, a strong narrative is the reason for the US economy’s strength.

But motivational speakers often end up repelling the very people they once inspired. Witness the reactions of students at Trump University, the fraud-based school its namesake founded in 2005, which shut down by multiple lawsuits a half-decade later. Or consider the sudden political demise of US Senator Joe McCarthy in 1954, after he carried his anti-communist rhetoric too far.

There is too much randomness in Trump’s management of the presidency to make persuasive predictions. He will surely try to stick to his public narrative, which has worked so well for so long. But a severe recession may be his undoing. And even before economic catastrophe strikes, the public may begin paying more attention to his aberrations – and to contagious new counternarratives that crowd out his own.

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 186

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 549

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 1K