Hypokalemic Paralysis In A Bodybuilder

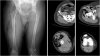

Mr BB reported that he had always lived healthy, neither smoked nor drank alcohol, and regularly engaged in sports. Until the age of 17 years, he had played in his country's national volleyball team but had to retire after being diagnosed with spina bifida occulta. Consequently, Mr BB started with bodybuilding at the age of 18 years. For the last 2 years, he has been a professional bodybuilder and participated in several national and international competitions. The last competition took place the day before admission.

Mr BB's preparation for competitions includes a strict diet as well as the misuse of different pharmacologic substances, in particular, anabolic steroids, human growth hormone, thyroid hormones, and fast-acting insulin. Besides the intended anabolic effects, Mr BB had never experienced any adverse effects, except for 1 episode of hypoglycemia. For the first time in his career, our patient took 2 × 80 mg of furosemide orally 24 and 48 hours before the competition, respectively, for better muscle definition. He noticed a pronounced diuretic effect and lost 5 to 6 kg of bodyweight due to nocturia but otherwise felt fit to compete the next morning.

The day after the competition, our patient felt unusually tired and took a nap in the early evening. When he woke up, he felt palpitations and could barely move his extremities. He managed to get out of bed but fell to the ground. A neighbor called the ambulance, and Mr BB was taken to our department.

At initial presentation, Mr BB was in moderate distress. Clinical examination yielded a 2.0-m tall and 115-kg heavy man with no major abnormalities except for pronounced generalized muscle hypertrophy and impaired ability to move. Vital parameters at presentation were as follows: Blood pressure (BP), 136/65 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 114 beats per minute; body temperature, 36.9ºC; and 95% peripheral oxygen saturation on room air. Urine drug screening was negative.

Initial venous blood gas analysis (ABL800 Flex; Radiometer Medical, Brønshøj, Denmark) yielded severe hypokalemia (1.6 mmol/L; reference range [RR], 3.4-4.5 mmol/L), hyperglycemia (521 mg/dL; RR, 70-120 mg/dL), and hyperlactatemia (2.7 mmol/L; RR, 0.0-1.8 mmol/L). Complete blood work additionally revealed low phosphate levels (b0.32 mmol/L; RR, 0.81-1.45 mmol/L) and elevated liver function parameters (aspartate aminotransferase, 61 U/L; RR, b35 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 134 U/L; RR, b45 U/L) as well as elevated lactate dehydrogenase (397 U/L; RR, b248 U/L) and elevated creatine kinase (1006 U/L; RR, b190 U/L) with a slightly elevated muscle brain fraction (26.2 U/L; RR, b24 U/L) and a slightly elevated troponin T value (0.047 ng/mL; RR, 0-0.03 ng/mL).

The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed artifacts due to shivering, sinus tachycardia (HR, 115 per minute), normal axis, normal PQ time, and pronounced U waves associated with severe hypokalemia (Fig. 2). After treatment with 500-mL Elozell spezial solution (containing 48-mmol potassium, 12-mmol magnesium, 32-mmol chloride, 40-mmol aspartate) and 1000-mL KADC solution (containing 25-mmol potassium, 10-mmol phosphate, 1.0-mmol calcium, 65-mmol chloride) over the next 7 hours, our patient's symptoms gradually improved; the potassium level (3.9 mmol/L), blood glucose level, and the ECG normalized (Fig. 3). Mr BB was discharged the next morning.

Severe hypokalemia is a potentially life-threatening disorder and is associated with variable degrees of skeletal muscle weakness, even to the point of paralysis. On rare occasions, diaphragmatic paralysis from hypokalemia can lead to respiratory arrest. There may also be decreased motility of smooth muscle, manifesting with ileus or urinary retention. Rarely, severe hypokalemia may result in rhabdomyolysis. Other manifestations of severe hypokalemia include alteration of cardiac tissue excitability and conduction. Hypokalemia can produce ECG changes such as U waves, T-wave flattening, and arrhythmias, especially if the patient is taking digoxin.

Common causes of hypokalemia include extrarenal potassium losses (vomiting, diarrhea) and renal potassium losses (eg, hyperaldosteronism, renal tubular acidosis, severe hyperglycemia, potassium-depleting diuretics) as well as hypokalemia due to potassium shifts (eg, insulin administration, catecholamine excess, familial periodic hypokalemic paralysis, thyrotoxic hypokalemic paralysis). Although the extent of diuretic misuse in professional bodybuilding is unknown, it may be regarded as substantial. Hence, diuretics must always be considered as a cause of hypokalemic paralysis in bodybuilders.

The treatment of hypokalemia consists of minimizing further potassium loss and providing potassium replacement. Intravenous administration of potassium is indicated when arrhythmias are present or hypokalemia is severe (potassium level of b2.5 mEq/L). Gradual correction of hypokalemia is preferable to rapid correction unless the patient is clinically unstable. Administration of potassium may be empirical in emergent conditions. When indicated, the maximum amount of intravenous potassium replacement should be 10 to 20 mEq/h with continuous ECG monitoring during infusion.

Mayr FB, Domanovits H, Laggner AN. Hypokalemic paralysis in a professional bodybuilder. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. ScienceDirect - The American Journal of Emergency Medicine : Hypokalemic paralysis in a professional bodybuilder

Severe hypokalemia is a potentially life-threatening disorder and is associated with variable degrees of skeletal muscle weakness, even to the point of paralysis. On rare occasions, diaphragmatic paralysis from hypokalemia can lead to respiratory arrest. There may also be decreased motility of smooth muscle, manifesting with ileus or urinary retention. Rarely, severe hypokalemia may result in rhabdomyolysis. Other manifestations of severe hypokalemia include alteration of cardiac tissue excitability and conduction. Hypokalemia can produce electrocardiographic changes such as U waves, T-wave flattening, and arrhythmias, especially if the patient is taking digoxin.

Common causes of hypokalemia include extrarenal potassium losses (vomiting and diarrhea) and renal potassium losses (eg, hyperaldosteronism, renal tubular acidosis, severe hyperglycemia, potassium-depleting diuretics) as well as hypokalemia due to potassium shifts (eg, insulin administration, catecholamine excess, familial periodic hypokalemic paralysis, thyrotoxic hypokalemic paralysis). Although the extent of diuretic misuse in professional bodybuilding is unknown, it may be regarded as substantial. Hence, diuretics must always be considered as a cause of hypokalemic paralysis in bodybuilders. We report on a 26-year-old man, Mr BB, who was admitted to the Vienna General Hospital emergency department because of severe generalized muscle cramps, paralysis, and palpitations.