Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing limit reached

- You have reached the maximum number of guest views allowed

- Please register below to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

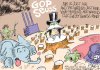

Trump Timeline ... Trumpocalypse

- Thread starter CdnGuy

- Start date

To paraphrase the FBI Director: Everything the WH said publicly was a complete lie.

Chief of Staff John Kelly's White House enemies are ready to use FBI Director Chris Wray's testimony as a weapon: "Wray’s FBI timeline makes one thing clear: the Kelly coverup is unraveling right before our eyes," a White House official says.

Kelly’s allies insist he knew nothing about the domestic violence until the Daily Mail story and that former White House aide Rob Porter misled Kelly to get the positive statement. (Porter denies this and tells associates he gave Kelly a full picture of what would be in the story, and denied the more serious accusations of physical abuse.)

Kelly’s story — that he acted immediately and decisively “within 40 minutes” to terminate Porter last Tuesday night — is also undermined by what multiple White House officials told reporters in real time. They said on Wednesday that nobody asked Porter to resign and in fact several senior officials asked him to “stay and fight.”

Why this matters: Kelly had overseen relative calm among White House staff since his appointment. The bungled response to allegations of abuse by Porter has thrown that into disarray.

Go deeper: How the FBI director contradicted the White House on the Porter timeline

Testifying under oath to the Senate Intelligence Committee, FBI Director Chris Wray on Tuesday said that the White House had been aware of problems with Porter months ago. Wray said that the FBI delivered a partial report in March 2017 and completed its report in late July. He said the bureau had provided further information in November, pursuant to a request.

“I’m quite confident that in this particular instance the FBI followed the established protocols,” he said.

Wray’s testimony aligns with reporting about what staff in White House, including Counsel Don McGahn and Chief of Staff John Kelly, knew and when they knew it, but it conflicts with the White House line, which is that when Kelly learned that Porter had been accused of domestic violence, he quickly told Porter that he needed to resign. (In yet another account, White House spokespeople have repeatedly claimed publicly Porter resigned of his own volition.) This testimony from Wray, who Trump selected to succeed fired FBI Director James Comey, puts his bureau, which has already been a target of harsh attacks from the president, again at odds with the White House.

It also demonstrates the weaknesses in the security-clearance process. Per Wray’s testimony, the White House knew in summer of 2017 that Porter would not be recommended for clearance, and yet it kept him on—in part, Washington Post reporting indicates, because the administration was so desperate for competent staffers that it was concluded Porter was indispensable. In fact, CNN reports he was under consideration for promotion to deputy chief of staff.

How could it be that Porter was still working with an interim clearance, and perhaps in line for a promotion, even after the FBI had delivered a report that recommended he not be granted clearance? In addition to showing how unseriously the White House treated the abuse allegations, this shows a fundamental truth of the clearance process: There’s no mechanism to enforce it.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 186

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 566

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 1K

Sponsors

Latest posts

-

-

-

-

Wuhan Wansheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (USA, International)

- Latest: Andrewthatguy