Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing limit reached

- You have reached the maximum number of guest views allowed

- Please register below to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Trump Timeline ... Trumpocalypse

- Thread starter CdnGuy

- Start date

xy5jn0

New Member

xy5jn0

New Member

Mike Pompeo was supposed to rescue the State Department from its disastrous start in the Trump presidency. When he first turned up at Foggy Bottom on May 1, he promised to staff up a badly depleted bureaucracy, listen to its views and reinvigorate U.S. diplomacy after a year of dysfunction. State, he said, would get “back our swagger.”

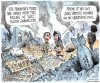

Now, after a month that has seen the secretary offer smiles and excuses to Saudi Arabia’s murderous Mohammed bin Salman, trash Congress for “caterwauling” and inspire a rare revolt by Senate Republicans, it’s time to offer a verdict: Pompeo has managed to worsen the State Department’s already abysmal standing with every significant constituency. Legislators, major allies, the media, career staff, even North Korea are alienated. The only satisfied customer may be President Trump — and even he has grounds for grievance.

“Swagger” diplomacy sounds like a contradiction in terms, but Pompeo has made it his motto. He launched his Instagram account in September by rebranding State as “the department of Swagger.” An op-ed he wrote for the Wall Street Journal last month was laced with it, contemptuously dismissing congressional and media outrage over the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. So was a speech he delivered last week in Brussels, in which he trashed the United Nations, the European Union, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the International Criminal Court, the Organization of American States, and, perhaps for good measure, the African Union.

The results? The Senate voted 63-to-37 to halt all U.S. support for Saudi Arabia’s calamitous intervention in Yemen, with 14 Republicans joining all 49 Democrats. The head of the IMF coolly observed that Pompeo didn’t know what he was talking about. And the European Unionwent ahead with plans to substitute euros for dollars in energy transactions, making it easier for the bloc to circumvent new U.S. sanctions on Iran.

xy5jn0

New Member

Check out @vulcanbomber2’s Tweet:

Konstantin Kilimnik trained in Russian military intelligence as a linguist; he spent decades by Paul Manafort’s side, serving as a translator and then rising through the ranks of his organization. Eventually, Manafort would come to describe Kilimnik—also known as K.K. or Kostya—as “My Russian Brain.” He would travel with Manafort to Moscow to meet with their client, the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska. When Kostya worked with Americans, they suspected him as some sort of spook. (Last June, I wrote this profile of him.)

When Paul Manafort cut a deal with Mueller in September, he promised to come clean. Any student of Manafort knows that coming clean is not a skill that comes naturally to the man. He built a career around his expertise at distorting images of scuzzy public figures; he made a fortune by erecting fantastically complicated financial contraptions that hid his money from governments, so ridiculously intricate that it is a miracle they worked in the first place. These habits of misdirection, this engrained proclivity toward the construction of expedient narratives, can’t be easily shed.

Everything we know about Paul Manafort also suggests that he would never stop working the angles. If there was a prospect of a presidential pardon, no matter how distant, he would make a play for one. Still, I don’t think this sort of legal gamesmanship fully explains why Paul Manafort would have continued to lie to Robert Mueller, when he obviously knew the risks of misleading the Special Counsel’s Office—and when Manafort had ample personal evidence of Trump’s flakiness and indifference to the fate of loyal servants.

Of course, it’s hard to see exactly where Mueller intends to take his investigation; we must take into account the redactions in his filings and his necessary silence about matters he continues to investigate. But I think there’s a reason that he seems to care so much about Kilimnik—and Manafort’s alleged lies about him.

xy5jn0

New Member

xy5jn0

New Member

xy5jn0

New Member

xy5jn0

New Member

It was President Trump’s signature campaign promise: he would build a wall along the nation’s southern border and it would be paid for by Mexico.

Shortly after becoming president, Trump dropped the Mexico part, turning to Congress for the funds instead. When that too failed — Congress earlier this year appropriated money for border security that could not be spent on a concrete wall — Trump nevertheless declared victory: “We’ve started building our wall,” he said in a speech on March 29. “I’m so proud of it.”

Despite the facts, which have been cited numerous times by fact checkers, Trump repeated his false assertion on an imaginary wall 86 times in the seven months before the midterm elections, according to a database of false and misleading claims maintained by The Post.

Trump’s willingness to constantly repeat false claims has posed a unique challenge to fact checkers. Most politicians quickly drop a Four-Pinocchio claim, either out of a duty to be accurate or concern that spreading false information could be politically damaging.

Not Trump. The president keeps going long after the facts are clear, in what appears to be a deliberate effort to replace the truth with his own, far more favorable, version of it. He is not merely making gaffes or misstating things, he is purposely injecting false information into the national conversation.

To accurately reflect this phenomenon, The Washington Post Fact Checker is introducing a new category – the Bottomless Pinocchio. That dubious distinction will be awarded to politicians who repeat a false claim so many times that they are, in effect, engaging in campaigns of disinformation.

The bar for the Bottomless Pinocchio is high: the claims must have received three or four Pinocchios from The Fact Checker and they must have been repeated at least 20 times. Twenty is a sufficiently robust number that there can be no question the politician is aware his or her facts are wrong. The list of Bottomless Pinocchios will be maintained on its own landing page.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 186

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 35

- Views

- 616

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 1K

Sponsors

Latest posts

-

-

MESO-Rx Sponsor Pharmacom Labs officials and our Basicstero.com store

- Latest: Steroidify Rep

-

-

-