Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing limit reached

- You have reached the maximum number of guest views allowed

- Please register below to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

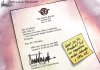

Trump Timeline ... Trumpocalypse

- Thread starter CdnGuy

- Start date

WASHINGTON — A top official with the Department of Health and Human Services told members of Congress on Thursday that the agency had lost track of nearly 1,500 migrant children it placed with sponsors in the United States, raising concerns they could end up in the hands of human traffickers or be used as laborers by people posing as relatives.

The official, Steven Wagner, the acting assistant secretary of the agency’s Administration for Children and Families, disclosed during testimony before a Senate homeland security subcommittee that the agency had learned of the missing children after placing calls to the people who took responsibility for them when they were released from government custody.

The children were taken into government care after they showed up alone at the Southwest border. Most of the children are from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, and were fleeing drug cartels, gang violence and domestic abuse, government data shows.

From last October to the end of the year, officials at the agency’s Office of Refugee Resettlement tried to reach 7,635 children and their sponsors, Mr. Wagner testified. From these calls, officials learned that 6,075 children remained with their sponsors. Twenty-eight had run away, five had been removed from the United States and 52 had relocated to live with a nonsponsor.

As the U.S.’s deranged president threatens to go to war in Syria and possibly beyond, it is worth re-examining how Trump views the troops whose lives he is putting on the line. For all his macho posturing and exhortations about his beloved generals, Trump–a draft dodger who referred to avoiding STDs as “my personal Vietnam”–has long treated veterans and their loved ones with contempt. This contempt is not rooted in an aversion to the military as an institution–Trump bloatedthe military budget and has been striking the Middle East while threatening North Korea and other states–but an aversion to the concept of service to one’s nation itself.

Serving one’s country is a sacrifice, and sacrifice terrifies Trump. The idea that one would risk oneself–out of love, loyalty, or duty–is alien to him. Sacrifice, to Trump, is a sucker’s bet, a gamble beyond his comprehension–but one he is all too willing to let other Americans make.

...

As Mueller and the FBI penetrate Trump’s criminal and Kremlin-tied inner circle, Trump will again take solace in predictable disaster–and there is no surer route to predictable disaster than John Bolton, the newly appointed national security adviser for whom war has long been the answer to every question. Like Trump, Bolton has advocatedpreemptive strikes, including the use of nuclear weapons; is willing to fabricate information to justify policies; and has a reputation as an Islamophobe. Similar to the ruthless lawyers with whom Trump surrounded himself in the past, Bolton provides the bureaucratic knowledge Trump lacks, but matches him in sadism. Bolton’s appointment led to a number of foreign policy analysts wondering if the end was nigh.

...

The U.S. has had presidents who used the military to distract from domestic disasters, fabricated pretexts for war, or showed apathy toward civilian casualties. But we have never had a president whose greatest loyalty appears to be to foreign backers, nor have we had a pan-warmonger as national security adviser in an administration with a barely functioning State Department. It is difficult to say whether the U.S. winning a war–in a conventional sense–is the goal of Trump and Bolton at all.

That may sound strange–Trump’s obsession with “winning” is infamous. But the winning is always more about Trump more than it is about the United States–and at times the concepts are mutually exclusive. Trump’s definition of an attack on the U.S. is when his lawyer’s home is raided by the FBI, not when Russia attacks our elections and infrastructure. As president, his main goals have been building a kleptocracy and dodging criminal prosecution, and any war– particularly when it involves Russia–will be enacted with those twin aims in mind. If Trump distracts the public from his own misdeeds, and financially benefits and consolidates power through war, it will not matter to him how many lives are lost–including the lives of U.S. servicemen and servicewomen. His callousness toward U.S. troops places him in stark contrast to any predecessor.

Bolton is similarly unconventional. Unlike the vast majority of state officials, he does not regret the Iraq War, and has seemingly learned nothing from its failures. His main regret seems to be that his desire for a similarly reckless invasion of other nations was not carried out. But Trump, with his visceral revulsion at the concept of service, is still the greatest danger. It is Trump whose past has finally caught up with him; it is Trump who stands the most to lose; it is Trump who unilaterally can launch nuclear weapons. Trump has shown that human beings have little inherent value to him. If Trump senses he may have to make a personal sacrifice, he will sacrifice the world instead.

SEOUL — President Trump credited his “maximum pressure” campaign of sanctions and threats with bringing North Korea to the negotiating table to discuss its nuclear weapons program. Now, having abruptly decided to call off an unprecedented summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in Singapore next month, Trump looks poised to revert to a hard line approach.

There’s just one problem: “The multilateral pressure coalition has fallen apart,” says Mira Rapp-Hooper, an East Asia expert at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center.

The United States had relied on Beijing to enforce international sanctions against North Korea, given that 90 percent of the isolated state’s trade goes to or through China. Now, with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo saying Thursday that more sanctions are coming, China will be needed more than ever.

But in Asia, many hold Trump, not Kim, responsible for the sudden collapse of diplomacy.

From here, Kim looks like the levelheaded leader who was trying to build confidence — releasing American detainees, blowing up the nuclear testing site — while Trump looks impetuous and unreliable.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 186

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 35

- Views

- 612

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 1K