Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing limit reached

- You have reached the maximum number of guest views allowed

- Please register below to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Trump Timeline ... Trumpocalypse

- Thread starter CdnGuy

- Start date

Jeremiahflex

Member

President Trump's decision Thursday to end subsidy payments to health insurance companies is expected to raise premiums for middle-class families and cost the federal government hundreds of billions of dollars.

The administration said it would stop reimbursing insurers for discounts on co-payments and deductibles that they are required by law to offer to low-income consumers. The reimbursements are known as cost-sharing reduction payments, or CSRs.

Insurance companies still have to give the discounts to low-income customers. So if the government doesn't reimburse the insurers, they'll make up the money by charging higher premiums for coverage.

Donald Trump is a self-help apostle. He always has tried to create his own reality by saying what he wants to be true. Where many see failure, Trump sees only success, and expresses it out loud, again and again.

“We have the votes” to pass a new health care bill, he said last month even though he and Republicans didn’t then and still don’t.

“We get an A-plus,” he said last week of his and his administration’s response to the devastating recent hurricanes as others doled out withering reviews.

“I’ve had just about the most legislation passed of any president, in a nine-month period, that’s ever served,” he said this week in an interview with Forbes, contradicting objective metrics and repeating his frequent and dubious assertion of unprecedented success throughout the first year of his first term as president.

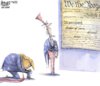

The reality is that Trump is in a rut. His legislative agenda is floundering. His approval ratings are historically low. He’s raging privately while engaging in noisy, internecine squabbles. He’s increasingly isolated. And yet his fact-flouting declarations of positivity continue unabated. For Trump, though, these statements are not issues of right or wrong or true or false. They are something much more elemental. They are a direct result of the closest thing the stubborn, ideologically malleable celebrity businessman turned most powerful person on the planet has ever had to a devout religious faith.

...

“The degree of positive thinking that we talk about in the paper bears no resemblance to what President Trump is exhibiting on a daily basis, which would be an extreme form of what we talked about,” said Brown from the University of Washington. “What we were really looking at was sort of … should you know what you are really like? Is a person best served by knowing what they are really like? And I think the answer to that is no. You’re better served believing you are a little bit better than you are—but not wildly …”

Brown cited the opening salvo of the Trump administration: the fight over the size of the turnout at his Inauguration. He somehow saw a crowd that was larger than it factually was, and said so. That, Brown said, isn’t self-confidence or self-assertion. “That’s bizarre. That isn’t within the normal range of human behavior,” he said. “No psychologist would say that’s adaptive.”

“There is a lot to like in the idea of power of positive thinking,” Ed Diener, one of the country’s leading researchers of happiness, told me, “but of course it must be grounded in a degree of realism.”

And where’s that dividing line?

The dividing line, Diener said, “is when the delusions become dysfunctional.”

And where is that?

“Where the distortions become strong enough that they make one act irrationally, impulsively,” he said.

Dorado, Puerto Rico (CNN)Jose Luis Rodriguez waited in line Friday to fill plastic jugs in the back of his pickup truck with water for drinking, doing the dishes and bathing.

But there is something about this water Rodriguez didn't know: It was being pumped to him by water authorities from a federally designated hazardous-waste site, CNN learned after reviewing Superfund documents and interviewing federal and local officials.

Rodriguez, 66, is so desperate for water that this news didn't startle him.

"I don't have a choice," he said. "This is the only option I have."

More than three weeks after Hurricane Maria ravaged this island, more than 35% of the island's residents -- American citizens -- remain without safe drinking water.

In 1939, the German American Bund organized a rally of 20,000 Nazi supporters at Madison Square Garden in New York City. When Academy Award-nominated documentarian Marshall Curry stumbled upon footage of the event in historical archives, he was flabbergasted. Together with Field of Vision, he decided to present the footage as a cautionary tale to Americans. The short film, A Night at the Garden, premieres on The Atlantic today.

“The first thing that struck me was that an event like this could happen in the heart of New York City,” Curry told The Atlantic. “Watching it felt like an episode of The Twilight Zone where history has taken a different path. But it wasn’t science fiction – it was real, historical footage. It all felt eerily familiar, given today’s political situation.”

Rather than edit the footage into a standard historical documentary with narration, Curry decided to “keep it pure, cinematic, and unmediated, as if you are there, watching, and wrestling with what you are seeing. I wanted it to be more provocative than didactic – a small history-grenade tossed into the discussion we are having about White Supremacy right now.”

“The footage is so powerful,” continued Curry, “it seems amazing that it isn’t a stock part of every high school history class. This story was likely nudged out of the canon, in part because it’s scary and embarrassing. It tells a story about our country that we’d prefer to forget.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 186

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 30

- Views

- 478

- Replies

- 21

- Views

- 1K