The date October 12 has been much on my mind this year. It was on this day in 1936 that the fascist forces of General Francisco Franco celebrated El Día de la Raza, the Hispanic world’s alternate version of Columbus Day. Some three months earlier, Franco had begun a right-wing insurrection against the elected government of the Republic. His Falangist army soon controlled a large part of the country, including Salamanca. It was in the central hall of that ancient city’s university, founded in 1218 and the most renowned institute of higher learning in the land, that the fascists commemorated their “Day of the Race.” In front of numerous dignitaries and emboldened by a mob of nationalist youth and legionnaires, Franco’s friend and mentor General José Millán Astray desecrated that temple of learning with six words: ¡Abajo la inteligencia! ¡Viva la muerte! (“Down with intelligence! Long live death!”)

That phrase—so paradoxical, so absurd, so idiotic—would have been laughable had it not occurred in a Europe where Nazis were burning libraries and, along with their Italian allies, pushing innumerable artists, scientists, and writers into exile. In Spain, those words resonated no less ominously. Only weeks earlier, Federico García Lorca, one of the greatest writers in the Spanish language, a poet and playwright who had deployed the many angels of intelligence, had been executed in Granada by a nationalist death squad. Many more intellectuals were assassinated in the years that followed, along with peasants, workers, and students who had learned under the Republic to think and speak for themselves.

When I was growing up in Chile in the Fifties and Sixties, I was convinced that such a cataclysm could not happen to us. I was sure that intelligence was obviously to be hailed and death just as obviously to be deplored. The 1973 coup against the democratic government of Salvador Allende changed all that. Books were turned to ashes, musicians were shot, scientists and educators were tortured. Meanwhile, the military, inspired by the same fundamentalism and loathing that had raged in Franco’s Spain, derided intelligence and reveled in death. The intelligentsia, they insisted, was to blame for Chile’s upheavals and supposed decline.

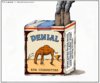

Today, Chile is democratic and monuments are lifted to those who were martyred by the dictatorship. The generals who ordered such horrors are reviled and some have even been jailed for their atrocities. If I now feel compelled to evoke the words Millán Astray used eighty-one years ago in Salamanca, it is because they have gained a bizarre relevance in today’s America. The resurgence of nationalism in our time has not yet reached the homicidal extremes it did when Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco misruled their lands, but the United States still faces an assault on rational discourse, scientific knowledge, and objective truth. And this war on intelligence, too, despite the edulcorated pieties that come from those who carry it out, will lead to many deaths.