Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

Guest viewing limit reached

- You have reached the maximum number of guest views allowed

- Please register below to remove this limitation

- Already a member? Click here to login

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dogs

- Thread starter Michael Scally MD

- Start date

PupperQueen

New Member

Thats a good looking pupper ❤

Brandaddy

Member

EazyE

Member

Does anyone put their dog on cycles?

Unless your dog is sick and slowly dying of a wasting disease, or treatment of urinary incontinence in males, what would be the point of administering AAS to the animal? The increased risk of cancers and illness to the dog is high. Experimenting with cycles on your dog, is reckless behaviour. I would hope administering AAS to a dog would be performed by a vet if it is required.Does anyone put their dog on cycles?

Last edited:

Twistu

New Member

I once posted on here about my Ridgeback sadly after 14 years she passed away on 05/23/20 something bit her and 3 days later she was shutting down had all her shots so vet wanted 4k just to see inside stomach as whatever bit her or she ate he could n`t even tell what happened .And after 4k he would not guarantee her survival .So i had to make the fucked up decision to spare her pain hard thing very hard thing ,worst was could not be with her cause of this virus ...had to get off chest so many thanks .sorry if post ruins day .And for anyone drinking beer or a coffee her favourite pour out last sip for Zuri the Rhodesian ridge back Best Dog ever ..

EazyE

Member

My condolences on the loss of your family member and best friend.I once posted on here about my Ridgeback sadly after 14 years she passed away on 05/23/20 something bit her and 3 days later she was shutting down had all her shots so vet wanted 4k just to see inside stomach as whatever bit her or she ate he could n`t even tell what happened .And after 4k he would not guarantee her survival .So i had to make the fucked up decision to spare her pain hard thing very hard thing ,worst was could not be with her cause of this virus ...had to get off chest so many thanks .sorry if post ruins day .And for anyone drinking beer or a coffee her favourite pour out last sip for Zuri the Rhodesian ridge back Best Dog ever ..

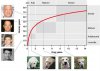

[OA] Quantitative Translation of Dog-to-Human Aging by Conserved Remodeling of the DNA Methylome

Highlights

· Oligo-capture sequencing of methylomes from 104 Labradors, 0–16 years old

· Methylome similarity translates dog years to human years logarithmically

· Conserved age-related changes predominately impact developmental gene networks

· Formulation of a conserved epigenetic clock transferable across mammals

All mammals progress through similar physiological stages throughout life, from early development to puberty, aging, and death. Yet, the extent to which this conserved physiology reflects underlying genomic events is unclear.

Here, we map the common methylation changes experienced by mammalian genomes as they age, focusing on comparison of humans with dogs, an emerging model of aging.

Using oligo-capture sequencing, we characterize methylomes of 104 Labrador retrievers spanning a 16-year age range, achieving >150× coverage within mammalian syntenic blocks.

Comparison with human methylomes reveals a nonlinear relationship that translates dog-to-human years and aligns the timing of major physiological milestones between the two species, with extension to mice.

Conserved changes center on developmental gene networks, which are sufficient to translate age and the effects of anti-aging interventions across multiple mammals.

These results establish methylation not only as a diagnostic age readout but also as a cross-species translator of physiological aging milestones.

Wang T, Ma J, Hogan AN, et al. Quantitative Translation of Dog-to-Human Aging by Conserved Remodeling of the DNA Methylome. Cell Systems. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2020.06.006

How Old Is Your Dog in Human Years? Scientists Develop Better Method than ‘Multiply by 7’

https://health.ucsd.edu/news/releases/Pages/2020-07-02-how-old-is-your-dog-in-human-years.aspx

If I had to choose between spending time with one good dog or five good people, I’d pick the dog every day of the week and twice on Sundays.

That may sound anti-social, but it’s a pragmatic choice, driven by data.

People, even the good ones, have more flaws than dogs. People, even the good ones, struggle to love without conditions. And dogs, at least the ones I’ve known, talk less than humans while managing to say more.

We bipedal ape-descendants don’t deserve dogs, yet they accept and adore us. Then they leave, always far too soon. And we are stuck with our dumb human flaws, and a dog-sized hole in our day-to-day.

I had to say farewell to a good dog last week, on a pantingly hot July 3 afternoon. She had cancer and there was nothing we could do these past couple of months except love her and spoil her and give her approximately a million behind-the-ear scritches and wait until she let us know it was time to go.

There are far more important things happening in the world right now than the death of a newspaper columnist’s dog. I know that. But here I am, writing about the dog who was near me, often with her head on my arm, as I wrote most of the columns you’ve read over the years.

Zoe was about 6 months old when we got her. She had a boulder-sized head with batlike ears, four pie-sized paws and a more traditionally puppy-esque body, making her look like something had gone tragically wrong at the dog factory six months earlier. Her body was largely white but her head was dark brown, like she had dunked her noggin in a vat of chocolate syrup.

But she was sweet and already house-trained, and her eyes revealed an intelligence that we bet would easily compensate for any head/body/paw proportionality issues.

She grew and grew, then grew some more and finally reached a robust 95 pounds. She was weirdly beautiful, and people often admired her and asked what breed she was.

“I’m not exactly sure,” I’d say, “but I believe she’s part cow.”

Zoe never took offense.

Her life story is that of any good family dog. Long walks. Fun times romping in the snow. Ample barking at delivery people and passing dogs.

In her later years she developed a strange relationship with a rabbit living in our backyard. They seemed to have reached a nonaggression pact that gave the rabbit unfettered access to all grass and plants while still allowing Zoe to occasionally save face by chasing the rabbit for about 6 feet before giving up and pretending she had better things to do.

Whatever ancestral wolf DNA she possessed had been fully overwhelmed by laziness or a tender heart, or possibly both. And that was fine. We had no need for a wolf. All we needed was Zoe.

And that’s what’s amazing about the creatures we’re lucky enough to have in our lives. They are, wholly and completely, themselves. Sure, we train them and help them adapt to our ways of living. But they train us to understand and appreciate them as beings unencumbered by the annoying complexities of humanness.

That’s what binds us so tightly, I think. Zoe’s inherent goodness made the people who loved her better by helping us see that her way of living — Love people! Love playing! Love food! — almost always made more sense than our own.

That’s a gift, one that remains long after our noble beasts have gone.

And it’s worth it. Even for the pain that comes on a hot July day, when you look at your friend and writing partner and know it’s time for her to go. And you hold her as her sweet soul leaves her body, and the humans left behind cry so hard their faces hurt.

It’s worth it, pain and tears and all.

My arm feels lighter as I write this, and notably less draped in slobber. There isn’t a bark when the doorbell rings, and there’s a 95-pound space in our family that won’t be easily filled.

We don’t deserve dogs. But we have them.

For that, I’m forever grateful.

Twistu

New Member

Sorry for your loss Mike... One hell of a year shed a tear reading post some things can never be replaced only set aside for new memories ..

Uglyrichie

New Member

How do I put my foot down without ww3 We just got a black lab puppy a week ago and my wife came through the door today with a sweatshirt and a rain coat for him. I can deal with the non stop toys but at cloths I think I need to draw a line. Any suggestions greatly appreciated.

Uglyrichie

New Member

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 383

- Replies

- 64

- Views

- 8K