Temporal Scaling of Carbon Emission and Accumulation Rates: Modern Anthropogenic Emissions Compared to Estimates of PETM Onset Accumulation

The Paleocene‐Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) is a global greenhouse warming event that happened 56 million years ago, causing extinction in the world's oceans and accelerated evolution on the continents.

It was caused by release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

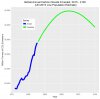

When we compare the rate of release of greenhouse gases today to the rate of accumulation during the PETM, we must compare the rates on a common time scale.

Projection of modern rates to a PETM time scale is tightly constrained and shows that we are now emitting carbon some 9–10 times faster than during the PETM.

If the present trend of increasing carbon emissions continues, we may see PETM‐magnitude extinction and accelerated evolution in as few as 140 years or about five human generations.

Gingerich PD. Temporal Scaling of Carbon Emission and Accumulation Rates: Modern Anthropogenic Emissions Compared to Estimates of PETM Onset Accumulation. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2019;34:329-35. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018PA003379

The Paleocene‐Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) was caused by a massive release of carbon to the atmosphere. This is a benchmark global greenhouse warming event that raised temperatures to their warmest since extinction of the dinosaurs.

Rates of carbon emission today can be compared to those during onset of the PETM in two ways:

(1) projection of long‐term PETM rates for comparison on an annual time scale and

(2) projection of short‐term modern rates for comparison on a PETM time scale.

Both require temporal scaling and extrapolation for comparison on the same time scale. PETM rates are few and projection to a short time scale is poorly constrained.

Modern rates are many, and projection to a longer PETM time scale is tightly constrained—modern rates are some 9–10 times higher than those during onset of the PETM.

If the present trend of anthropogenic emissions continues, we can expect to reach a PETM‐scale accumulation of atmospheric carbon in as few as 140 to 259 years (about 5 to 10 human generations).

The Paleocene‐Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) is a global greenhouse warming event that happened 56 million years ago, causing extinction in the world's oceans and accelerated evolution on the continents.

It was caused by release of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

When we compare the rate of release of greenhouse gases today to the rate of accumulation during the PETM, we must compare the rates on a common time scale.

Projection of modern rates to a PETM time scale is tightly constrained and shows that we are now emitting carbon some 9–10 times faster than during the PETM.

If the present trend of increasing carbon emissions continues, we may see PETM‐magnitude extinction and accelerated evolution in as few as 140 years or about five human generations.

Gingerich PD. Temporal Scaling of Carbon Emission and Accumulation Rates: Modern Anthropogenic Emissions Compared to Estimates of PETM Onset Accumulation. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2019;34:329-35. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018PA003379

The Paleocene‐Eocene thermal maximum (PETM) was caused by a massive release of carbon to the atmosphere. This is a benchmark global greenhouse warming event that raised temperatures to their warmest since extinction of the dinosaurs.

Rates of carbon emission today can be compared to those during onset of the PETM in two ways:

(1) projection of long‐term PETM rates for comparison on an annual time scale and

(2) projection of short‐term modern rates for comparison on a PETM time scale.

Both require temporal scaling and extrapolation for comparison on the same time scale. PETM rates are few and projection to a short time scale is poorly constrained.

Modern rates are many, and projection to a longer PETM time scale is tightly constrained—modern rates are some 9–10 times higher than those during onset of the PETM.

If the present trend of anthropogenic emissions continues, we can expect to reach a PETM‐scale accumulation of atmospheric carbon in as few as 140 to 259 years (about 5 to 10 human generations).