cvictorg

New Member

Sea Surface Temperatures Along U.S. East Coast Highest In 150 Years During 2012

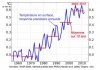

The warmest year on record for the continental U.S. also brought the warmest recorded sea surface temperatures in 150 years for the East Coast between Cape Hatteras, N.C. and the Gulf of Maine.

Using satellite and ship-board measurements, NOAA's Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) reported that average surface temperatures reached 57.2 F (14 C) in 2012, beating the previous record set in 1951. 2012's temperature rise also marked the largest single-year increase since records began in 1854 and one of only five times that average temperatures have jumped by more than 1.8 F (1 C).

NOAA: 2012 Hottest & 2nd-Most Extreme Year On Record | Climate Central

It’s official: 2012 was the warmest year on record in the lower 48 states, as the country experienced blistering spring and summer heat, tinderbox fire weather conditions amid a widespread drought, and one of the worst storms to ever strike the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2012 had an average temperature of 55.3°F, which eclipsed 1998, the previous record holder, by 1°F. That was just off Climate Central’s calculation in mid-December, which projected an expected value of 55.34°F, based on historical data.

The 1°F difference from 1998 is an unusually large margin, considering that annual temperature records are typically broken by just tenths of a degree Fahrenheit. In fact, the entire range between the coldest year on record, which occurred in 1917, and the previous record warm year of 1998 was just 4.2°F.

The year consisted of the fourth-warmest winter, the warmest spring, second-warmest summer, and a warmer-than-average fall. With an average temperature that was 3.6°F above average, July became the hottest month ever recorded in the contiguous U.S. The average springtime temperature in the lower 48 was so far above the 1901-2000 average — 5.2°F, to be exact — that the country set a record for the largest temperature departure for any season on record.

"Climate change has had a role in this [record],” said Jake Crouch, a climate scientist at NOAA's National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, N.C. He said it isn't clear yet exactly how much of the temperature record was due to climate change compared to natural variability, but that it's unlikely such a record would have occurred without the long-term warming trend caused in large part by emissions of greenhouse gases.

During the summer, nearly 100 million people experienced 10 or more days with temperatures greater than 100°F, which is about one-third of the nation’s population, NOAA reported.

With 34,008 daily high temperature records set or tied the year compared to just 6,664 daily record lows — a ratio of about five high temperature records for every one low temperature record — 2012 was no ordinary weather year in the U.S. It wasn’t just the high temperatures that set records, though. Overnight low temperatures were also extremely warm, and in a few cases the overnight low was so warm that it set a high temperature record, a rare feat.

SS13.04 Spring Ecosystem Advisory: Sea Surface Temperatures Reach Highest Level in 150 Years on Northeast Continental Shelf

Ecosystem AdvisoryFor the Northeast Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem - Spring 2013

Sea Surface Temperature | Climate Change | US EPA

Summary of Conditions of the Northeast Shelf Ecosystem

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Northeast Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem during 2012 were the highest ever recorded in both long-term observational and short-term remote sensing time series. These exceptionally high SSTs are part of a pattern of elevated temperatures occurring in the Northwest Atlantic, but not seen elsewhere in the ocean basin.

The fall bloom on the Northeast Shelf was poorly developed with the exception of some bloom activity in the eastern Gulf of Maine; resources dependent on the fall bloom will experience a deficit in energy flow.

Chlorophyll concentration over the course of the year 2012 remained high compared to recent years despite low fall chlorophyll. The relatively high biomass level can be attributed to the above average 2012 spring bloom.

Reflecting the large jump in temperature of the ecosystem, Northeast Shelf warm water thermal habitat was at a record high level during 2012, whereas cold water habitat was at a record low level.

Winter mixing went to extreme depths in 2013, which will impact the spring bloom by redistributing nutrients and affecting the stratification of the water column as the bloom develops.

The warmest year on record for the continental U.S. also brought the warmest recorded sea surface temperatures in 150 years for the East Coast between Cape Hatteras, N.C. and the Gulf of Maine.

Using satellite and ship-board measurements, NOAA's Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) reported that average surface temperatures reached 57.2 F (14 C) in 2012, beating the previous record set in 1951. 2012's temperature rise also marked the largest single-year increase since records began in 1854 and one of only five times that average temperatures have jumped by more than 1.8 F (1 C).

NOAA: 2012 Hottest & 2nd-Most Extreme Year On Record | Climate Central

It’s official: 2012 was the warmest year on record in the lower 48 states, as the country experienced blistering spring and summer heat, tinderbox fire weather conditions amid a widespread drought, and one of the worst storms to ever strike the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 2012 had an average temperature of 55.3°F, which eclipsed 1998, the previous record holder, by 1°F. That was just off Climate Central’s calculation in mid-December, which projected an expected value of 55.34°F, based on historical data.

The 1°F difference from 1998 is an unusually large margin, considering that annual temperature records are typically broken by just tenths of a degree Fahrenheit. In fact, the entire range between the coldest year on record, which occurred in 1917, and the previous record warm year of 1998 was just 4.2°F.

The year consisted of the fourth-warmest winter, the warmest spring, second-warmest summer, and a warmer-than-average fall. With an average temperature that was 3.6°F above average, July became the hottest month ever recorded in the contiguous U.S. The average springtime temperature in the lower 48 was so far above the 1901-2000 average — 5.2°F, to be exact — that the country set a record for the largest temperature departure for any season on record.

"Climate change has had a role in this [record],” said Jake Crouch, a climate scientist at NOAA's National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, N.C. He said it isn't clear yet exactly how much of the temperature record was due to climate change compared to natural variability, but that it's unlikely such a record would have occurred without the long-term warming trend caused in large part by emissions of greenhouse gases.

During the summer, nearly 100 million people experienced 10 or more days with temperatures greater than 100°F, which is about one-third of the nation’s population, NOAA reported.

With 34,008 daily high temperature records set or tied the year compared to just 6,664 daily record lows — a ratio of about five high temperature records for every one low temperature record — 2012 was no ordinary weather year in the U.S. It wasn’t just the high temperatures that set records, though. Overnight low temperatures were also extremely warm, and in a few cases the overnight low was so warm that it set a high temperature record, a rare feat.

SS13.04 Spring Ecosystem Advisory: Sea Surface Temperatures Reach Highest Level in 150 Years on Northeast Continental Shelf

Ecosystem AdvisoryFor the Northeast Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem - Spring 2013

Sea Surface Temperature | Climate Change | US EPA

Summary of Conditions of the Northeast Shelf Ecosystem

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Northeast Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem during 2012 were the highest ever recorded in both long-term observational and short-term remote sensing time series. These exceptionally high SSTs are part of a pattern of elevated temperatures occurring in the Northwest Atlantic, but not seen elsewhere in the ocean basin.

The fall bloom on the Northeast Shelf was poorly developed with the exception of some bloom activity in the eastern Gulf of Maine; resources dependent on the fall bloom will experience a deficit in energy flow.

Chlorophyll concentration over the course of the year 2012 remained high compared to recent years despite low fall chlorophyll. The relatively high biomass level can be attributed to the above average 2012 spring bloom.

Reflecting the large jump in temperature of the ecosystem, Northeast Shelf warm water thermal habitat was at a record high level during 2012, whereas cold water habitat was at a record low level.

Winter mixing went to extreme depths in 2013, which will impact the spring bloom by redistributing nutrients and affecting the stratification of the water column as the bloom develops.