In the Netherlands, an iconic skating race — and a way of life — faces extinction from climate change.

LEEUWARDEN, Netherlands - On a balmy winter day, Klaas Einte Adema lugged his ice skates from car to rink to continue his training for a race that might never come. The 36-year-old has spent the better part of his adult life doing this — showing up at the rink six days a week, skating laps, honing technique and waiting for the weather to someday cooperate.

“When it’s coming, I’m ready,” he says of the country’s most storied and near-mythical sporting event.

The Elfstedentocht translates to “eleven cities tour.” It’s an ice skating race that measures about 135 miles and takes place on the canals that connect the 11 cities in the Friesland province of the Netherlands. The 110-year-old event is wildly popular — the next race is expected to attract 26,000 participants, 2 million spectators and 3,000 journalists and will surely draw the attention of nearly every person in the country — largely because of the long wait and grim forecast associated with it.

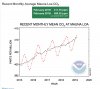

The race only takes place when conditions allow; when extreme winter bowls over the region, the temperatures drop, and the canals freeze over. But the Netherlands is no longer a romantic wintry wonderland, and there hasn’t been an Elfstedentocht since 1997, marking the longest drought ever between races. Climate change has endangered the race and is slowly dousing hopes across the province.

…